INTRODUCTION

One of the six Brazilian biomes, the Pantanal, formed by the geological depression of the Upper Paraguay basin, is the most extensive floodplain in the world1, encompassing an area of more than 110,000 km². Characterized by alternating flood and dry seasons2, the Pantanal floodplain has 1,863 species of plants, 269 of fish, 41 species of amphibians, 177 of reptiles, 470 species of birds, and 124 species of mammals3. There is no doubt that this number is much greater due to the vast territorial breadth, the broad range of habitats, and the small number of studies in the region. During the flood season, overflowed areas become linked to the large bays, allowing the movement of fishes and other aquatic organisms, while in the dry season, many animals are restricted to small areas, with high mortality due to the low oxygen concentration in the habitat and predation, among other factors4. Between 1998 and 2006, there was an increase in the number of conservation units in Pantanal, although they are still insufficient to ensure the regional biodiversity conservation5. Currently, there are 29 conservation units comprising 7,063 km² (4.68%), of which 4,394 km² (2.91%) are strictly protected areas and 2,669 km² (1.77%) are for sustainable use6.

Although there are relevant fauna and flora records from the Pantanal biome and on the influence of flood pulses on species occurrence7, these records correspond mostly to vertebrates, mainly fishes. Regarding malacofauna surveys, studies are restricted to broad taxonomic units without indicating the species8,9,10. To characterize the Pantanal biodiversity, some researchers have evaluated areas in the Pirizal grid in Pantanal northern. Considering aquatic invertebrates, from 12 taxa recorded11, Mollusca was observed in 74% of the sampled sites, represented only by Ampullariidae (Pomacea sp. and Marisa sp.) and Ancylinae. Similarly, Saulino and Trivinho-Strixino12 evaluated the macrophyte-associated aquatic macroinvertebrates of a lake in the Pantanal region (Corumbá, Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil) and reported only the genera Biomphalaria and Pomacea among the 20 taxa identified.

It is a consensus that biological invasions are recognized as one of the greatest threats to biodiversity in the world. The Asiatic species Corbicula largillierti (Philippi, 1844) and Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774) were recorded for the first time in Mato Grosso State, in Paraguay-Paraná basin upper course, in Cuiabá13, and Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) near a tributary of Cuiabá River, in 19982. The biological characteristics of these exotic species and their resistance to adverse environmental factors14 allow their population expansion, consequently affecting trophic chains15, the ecosystem structure16, and the habitats' biodiversity, generating both economic and environmental negative impacts17.

Thus, the present study provides an inventory of mollusk species found in the northern part of the Pantanal biome, reporting both the richness and freshwater malacofauna composition in four cities of Mato Grosso State, representing the most extensive malacofauna inventory in this area. In addition, the new occurrences and the presence of parasitic disease-transmitting or exotic mollusk species are highlighted to provide evidence to support health and conservation programs in this environmental preservation area that holds remarkable biodiversity in Central Brazil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study area was the cities of Barão de Melgaço, Cáceres, Poconé, and Santo Antônio do Leverger, situated in Pantanal northern part, Mato Grosso State, Brazil. The Mollusk Collection of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (CMIOC) database from Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) was consulted: samples collected by technicians from the defunct Superintendency of Public Health Campaigns (SUCAM) from 1978 to 1980, 1982 to 1985, 1988, and 1990; as well as samples from the field expeditions carried out by the Laboratory of Malacology team from Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC/Fiocruz) during 2002 to 2004, 2009 to 2011, 2016, and 2018. The snails were obtained by direct collection using a handled metallic sieve, and all sampling sites were georeferenced. Following collection, the specimens were placed in plastic jars, packed for transport to be processed and identified in the Laboratory of Malacology, IOC/Fiocruz.

All samples were identified by analyzing the shell and dissection of the specimens after being anesthetized (1% Hypnol) and fixed in Railliet-Henry solution18. When samples corresponded to very young animals or only shells, often quite damaged, the mollusks were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible according to the literature and consultation with experts.

Geographic coordinates obtained during the expeditions were used for the georeferencing, and when lacking, the information described in the database served as indicative of the location, which was georeferenced using the Google Maps program. The taxonomic groups identified at the species level were classified according to the frequency of occurrence19 into the categories according to periodicity: constant (present in more than 50% of the samples), accessory (between 50 and 25%), and accidental (less than 25%)20,21. Although there are records of bivalves, the present study did not include this taxonomic group in the frequency-of-occurrence analyses due to: 1) the focus of the surveys carried out by the SUCAM was Gastropoda; and 2) Bivalvia collection was casual, since the technique adopted during the expeditions was not appropriated for this taxonomic group. Considering only the Gastropoda, the species richness and the malacofauna composition are presented for each city. The latter was calculated using the first-order Jackknife and Chao 2 estimators, which consider the observed richness and the number of species with only one or two occurrences (rare species)20,21.

RESULTS

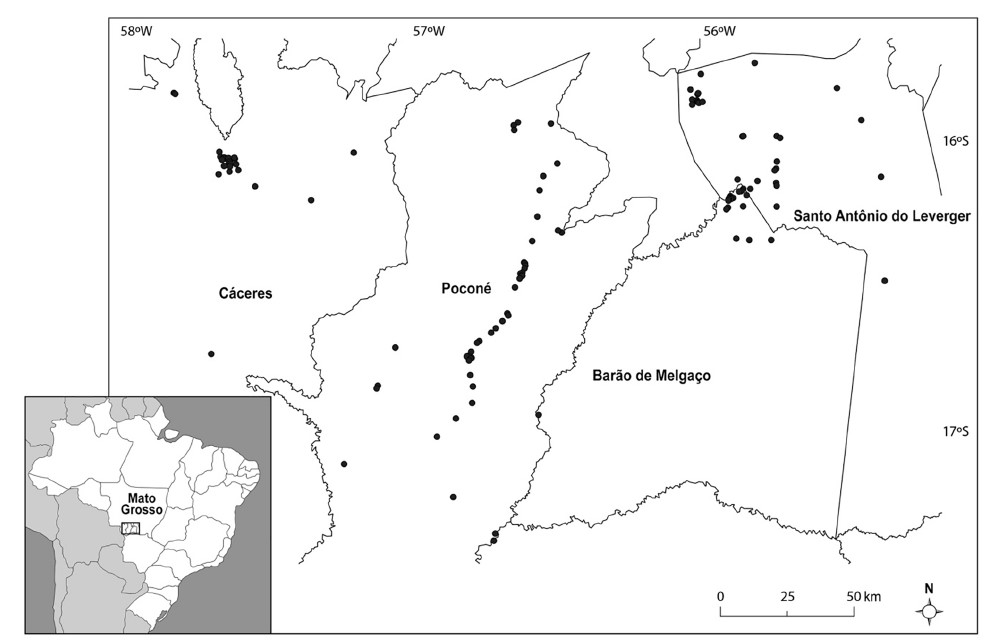

Of 130 georeferenced sites (Figure 1), 21 were in Barão de Melgaço, 25 in Cáceres, 29 in Santo Antônio do Leverger, and 55 in Poconé. Of these locations, 28 were analyzed more than once, such as Pixaim River, in Poconé, where the largest number of samples was collected (five). In addition to this site, 15 other places were analyzed more than once in Poconé, seven in Barão de Melgaço, three in Santo Antônio do Leverger, and two in Cáceres.

Figure 1 - Location of Mato Grosso State, Brazil, and cities that were surveyed for the snails' presence with georeferenced sites

Among the 547 records, 36 were Bivalvia, belonging to the four families Cyrenidae, Hyriidae, Mycetopodidae, and Sphaeriidae, and 511 were Gastropoda, belonging to the five families Ampullariidae, Physidae, Planorbidae, Pomatiopsidae, and Thiaridae.

The highest number of species was found in Santo Antônio Leverger (19 species), followed by Barão de Melgaço (17), Poconé (16), and Cáceres (15) (Table 1). The following 24 species were identified (Figures 2 and 3): Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774); Castalia ambigua Lamarck, 1819; Anodontites elongatus (Swainson, 1823); Anodontites trapesialis (Lamarck, 1819); Eupera tumida (Clessin, 1879); Eupera simoni (Jousseaume, 1889); Marisa planogyra Pilsbry, 1933; Pomacea lineata (Spix, 1827); Pomacea maculata Perry, 1810; Pomacea scalaris d'Orbigny, 1835; Stenophysa marmorata (Guilding, 1828); Antillorbis nordestensis (Lucena, 1954); Biomphalaria amazonica Paraense, 1966; Biomphalaria occidentalis Paraense, 1981; Biomphalaria straminea (Dunker, 1848); Drepanotrema anatinum (d'Orbigny, 1835); Drepanotrema cimex (Moricand, 1839); Drepanotrema lucidum (Pfeiffer, 1839); Drepanotrema depressissimum (Moricand, 1839); Gundlachia radiata (Guilding, 1828); Gundlachia ticaga (Marcus & Marcus, 1962); Uncancylus concentricus (d'Orbigny, 1835); Idiopyrgus souleyetianus Pilsbry, 1911; and Melanoides tuberculata (Müller, 1774). The malacofauna composition in the four cities is listed in table 1.

Table 1 - Species found in four cities of Pantanal northern, Mato Grosso State, Brazil

| Taxa | Cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barão de Melgaço | Cáceres | Poconé | Santo Antônio do Leverger | ||

| Bivalvia | Cyrenidae | ||||

| Corbicula fluminea | + | + | + | ||

| Hyriidae | |||||

| Castalia ambigua | + | ||||

| Mycetopodidae | |||||

| Anodontites elongatus | + | + | |||

| Anodontites trapesialis | + | + | + | ||

| Sphaeriidae | |||||

| Eupera simoni | + | ||||

| Eupera tumida | + | ||||

| Gastropoda | Ampullariidae | ||||

| Marisa planogyra | + | + | + | + | |

| Pomacea lineata | + | + | + | ||

| Pomacea maculata | + | + | + | + | |

| Pomacea scalaris | + | + | + | + | |

| Physidae | |||||

| Stenophysa marmorata | + | + | + | + | |

| Planorbidae | |||||

| Ancylinae | |||||

| Gundlachia radiata | + | + | + | + | |

| Gundlachia ticaga | + | + | + | + | |

| Uncancylus concentricus | + | ||||

| Planorbinae | |||||

| Antillorbis nordestensis | + | + | + | ||

| Biomphalaria amazonica | + | + | + | ||

| Biomphalaria occidentalis | + | + | + | + | |

| Biomphalaria straminea | + | + | + | ||

| Drepanotrema anatinum | + | + | + | + | |

| Drepanotrema cimex | + | + | |||

| Drepanotrema depressissimum | + | + | |||

| Drepanotrema lucidum | + | + | + | + | |

| Pomatiopsidae | |||||

| Idiopyrgus souleyetianus | + | ||||

| Thiaridae | |||||

| Melanoides tuberculata | + | + | |||

+: Species found.

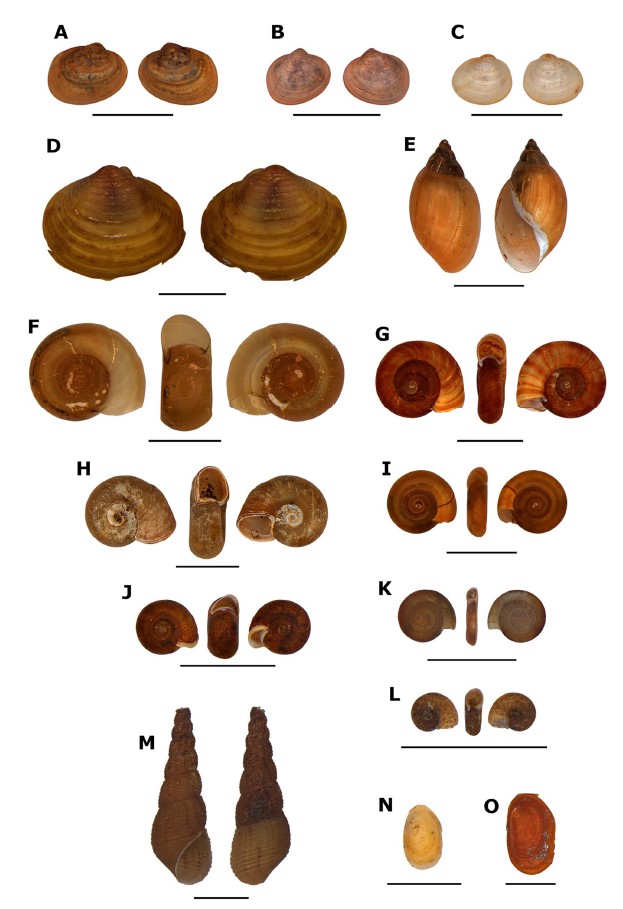

Photos: Eduardo da Silva Cinilha (Laboratory of Malacology, IOC/Fiocruz). A: Eupera simoni; B: Eupera tumida; C: Pisidium sp.; D: Corbicula fluminea; E: Stenophysa marmorata; F: Biomphalaria occidentalis; G: Biomphalaria amazonica; H: Biomphalaria straminea; I: Drepanotrema lucidum; J: Drepanotrema anatinum; K: Drepanotrema cimex; L: Antillorbis nordestensis; M: Melanoides tuberculata; N: Gundlachia radiata; O: Uncancylus concentricus. Scale bars: 5 mm.

Figure 2 - Freshwater mollusks of the families Sphaeriidae, Cyrenidae, Physidae, Planorbidae, and Thiaridae from Mato Grosso State, Brazil

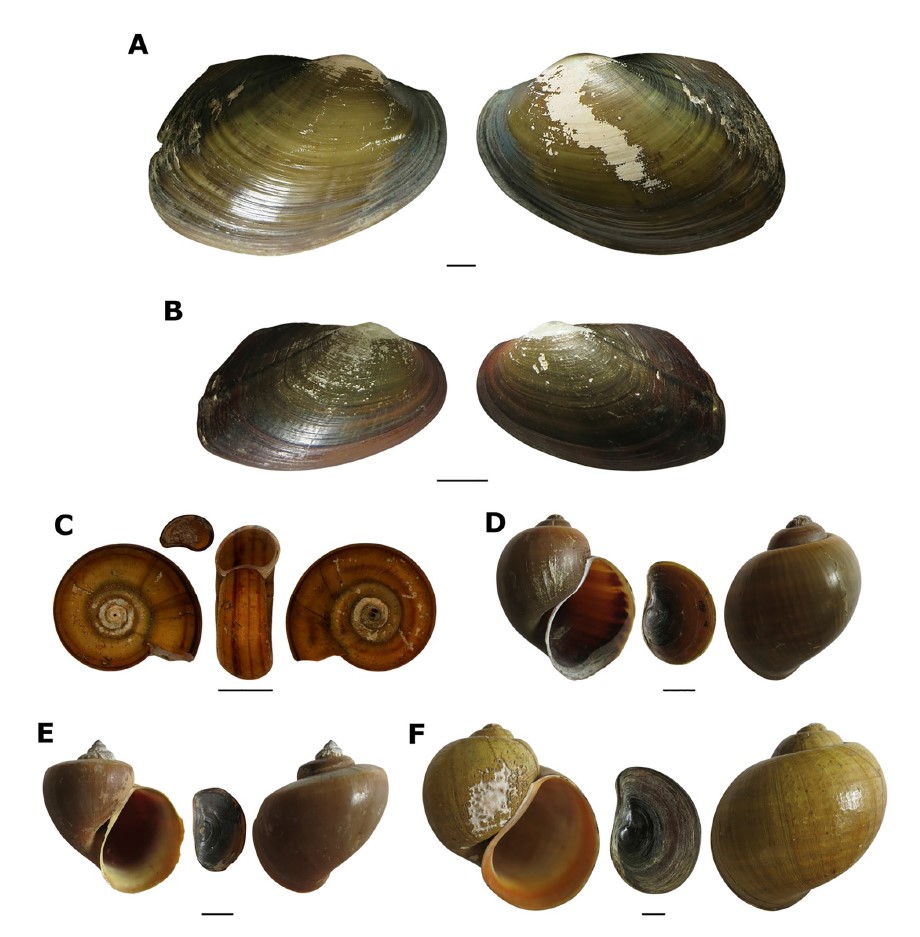

Photos: Eduardo da Silva Cinilha (Laboratory of Malacology, IOC/Fiocruz). A: Anodontites trapesialis; B: Anodontites elongatus; C: Marisa planogyra; D: Pomacea lineata; E: Pomacea scalaris; F: Pomacea maculata. Scale bars: 1 cm.

Figure 3 - Freshwater mollusks of the families Mycetopodidae and Ampullariidae from Mato Grosso State, Brazil

Only 36.1% of Bivalvia samples were identified to the species level: A. elongatus (two samples), A. trapesialis (four), C. ambigua (one), C. fluminea (four), E. tumida (one), and E. simoni (one). In addition to these, three samples of Anodontites sp. were also found (in Barão de Melgaço), ten of Eupera sp. (in three cities, excluding Cáceres), and one of Psidium sp. (in Santo Antônio do Leverger).

From 511 records of Gastropoda, 227 were Caenogastropoda and 284 were Heterobranchia, with a clear predominance of the Ampullariidae family (223 records). Among the two Pomatiopsidae samples collected in Cáceres, only one was identified. Regarding Heterobranchia, all 25 samples of the Physidae family were identified to the species level, and of the 259 records of Planorbidae, 6.9% (18/259) of the Planorbinae subfamily were identified to the species level, while 15.0% (39/259) of Ancylinae were not.

Over the whole study area, P. scalaris (present in 34.6% of the samples), P. maculata (30.1%), M. planogyra (25.6%), and D. lucidum (27.3%) were considered accessory species and the remaining species considered accidental, with the following frequencies of occurrence: B. occidentalis, 18.7%; D. anatinum, 17.0%; S. marmorata, 14.2%; B. amazonica; 13.6%; G. radiata, 24.4%; A. nordestensis, 3.4%; G. ticaga 3.4%; P. lineata, 2.8%; D. depressissimum, 2.8%; B. straminea, 1.7%; M. tuberculata, 1.1%; D. cimex, 1.1%; U. concentricus, 1.1%; and I. souleyetianus, 0.6%.

When the cities were analyzed separately, M. planogyra and P. scalaris were considered constant in Poconé. Those considered accessory species were B. amazonica (Barão de Melgaço only), B. occidentalis (Barão de Melgaço and Cáceres), D. anatinum (Barão de Melgaço), D. lucidum (Barão de Melgaço and Cáceres), G. radiata (Poconé), P. maculata (Barão de Melgaço and Poconé), and P. scalaris (Cáceres) (Table 2). According to the first-order Jackknife and Chao 2 estimators, the richness values in each locality were, respectively, 14.9 and 14.2 for Santo Antônio do Leverger, 17.9 and 14 for Poconé, 198.8 and 20.2 for Cáceres, and 18.9 and 17.7 for Barão de Melgaço.

Table 2 - Frequency-of-occurrence index (%) of the species present in four cities of Pantanal northern, Mato Grosso State, Brazil

| Species | Cities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barão de Melgaço | Cáceres | Poconé | Santo Antônio do Leverger | |

| Marisa planogyra | 6.7 | 7.1 | 52.6 | 2.8 |

| Pomacea lineata | 3.3 | - | 3.9 | 2.8 |

| Pomacea maculata | 40.0 | 21.4 | 36.8 | 20.0 |

| Pomacea scalaris | 23.3 | 35.7 | 52.6 | 11.4 |

| Stenophysa marmorata | 20.0 | 14.3 | 15.8 | 8.6 |

| Antillorbis nordestensis | 3.3 | - | 1.3 | 11.4 |

| Biomphalaria amazonica | 43.3 | - | 7.9 | 14.3 |

| Biomphalaria occidentalis | 33.3 | 25.0 | 14.5 | 14.3 |

| Biomphalaria straminea | 3.3 | 3.6 | 1.3 | - |

| Drepanotrema anatinum | 30.0 | 21.4 | 17.1 | 5.7 |

| Drepanotrema cimex | 3.3 | 3.6 | - | - |

| Drepanotrema depressissimum | 6.7 | - | - | 8.6 |

| Drepanotrema lucidum | 50.0 | 28.6 | 22.4 | 22.8 |

| Gundlachia ticaga | 6.7 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 5.7 |

| Gundlachia radiata | 13.3 | 17.8 | 35.5 | 20.0 |

| Uncancylus concentricus | - | 7.1 | - | - |

| Idiopyrgus souleyetianus | - | 3.6 | - | - |

| Melanoides tuberculata | - | 3.6 | 1.3 | - |

Conventional sign used: - Numeric data equal to zero, not resulting from rounding.

DISCUSSION

This study substantially increases the knowledge of the freshwater malacofauna in the Pantanal biome, especially regarding the Gastropoda. Although appropriate techniques for collecting Bivalvia were not adopted, finding A. trapesialis, A. elongatus, C. ambigua, C. fluminea, Eupera spp., and Pisidium spp. in the region confirms the records of Marçal and Callil22 and Callil et al.23. Regarding gastropods, Marçal and Callil22 reported only Ampullariidae (represented by M. planogyra, P. scalaris, and P. lineata), whereas, in the present study, 14 species were identified in Poconé. Junk et al.24 reported the presence of M. planogyra, P. scalaris, and P. lineata and their predation by the snail kite Rostrhamus sociabilis (Vieillot, 1817), especially at the beginning of the rainy season. In the Pantanal floodplain, many empty shells are found at snail kite feeding sites25. According to Thiengo et al.26, ampullariids serve as food for birds and a wide variety of other vertebrates and usually occur in dense populations, constituting an important link in trophic chains.

Populations of B. straminea, a species capable of transmitting the trematode Schistosoma mansoni Sambon, 1907, which causes schistosomiasis in Brazil, and B. amazonica, a potential host of this worm, were present in the study area. The locations where they were found were categorized as disease-free with transmission potential27. In these areas, the Ministry of Health indicates conducting epidemiological surveys, and any detected case of schistosomiasis should be reported and treated unless there is a formal contraindication. Fernandez and Thiengo28 analyzed the susceptibility of B. amazonica descendants to two S. mansoni strains (SJ and BH), and the infection rates were 33.33 (SJ) and 11.53% (BH) for Barão de Melgaço population; 0 and 5.88% for Poconé; and 10.0% for Santo Antônio do Leverger. Regarding B. straminea, although no experimental study has been conducted with these populations, the species is widely distributed in Brazil, present in 1,586 Brazilian cities29, and has great epidemiological importance, particularly in the country's Northeast Region, for maintaining high rates of human infection30. The present study expands the geographical distribution of B. straminea in Mato Grosso State by including Barão de Melgaço, Cáceres, and Poconé, which, added to Fernandez et al.31 records, totals 1,589 Brazilian cities.

As for the remaining species, the results of the present study complement the previous survey of freshwater malacofauna conducted by Paraense32, which analyzed 21 cities of Mato Grosso and found six species of Planorbidae, with a predominance of B. occidentalis (81% of municipalities) and D. lucidum (52%). From the four places analyzed, only Cáceres was reported in Paraense's study32, who found only three species there. Mollusks make possible the biological cycles of several trematodes involving birds, amphibians, fish, reptiles, and mammals, many of which are still unknown, as reported by Mattos et al.33, who recorded seven cercaria types in the study area.

Seasonal variations, with well-defined dry and wet seasons, influence malacofauna richness in the Pantanal region. In the dry season, many species are restricted to small biotopes, along with fish and reptiles, which feed on mollusks, as birds do. The ampullariids' predominance in the region might be due to their survival strategies, which enable the formation of new and abundant populations during the flooding period34.

We highlight the occurrence of exotic species in the area, such as M. tuberculata and C. fluminea, recorded for the first time in Brazil in 1967 and 1981, respectively, and currently present in several hydrographic basins17. The finding of C. fluminea in Barão de Melgaço confirms the record of Colle and Callil35. It reinforces the concern of researchers regarding its invasion potential, which affects native species in its areas of occurrence. A good example is the bivalve A. elongatus, a species categorized as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (2008)36. However, due to the lack of ecological and biological data, it was not included in the current list of Brazil's endangered species37. In addition to interspecific competition, the exotic snail M. tuberculata can host 17 families, 25 genera, and 37 species of trematodes38, including parasites with medical and veterinary importance, such as Centrocestus formosanus (Nishigori, 1924), the etiological agent of centrocestiasis in humans.

CONCLUSION

There has been an increase in tourism in Pantanal recently that, combined with the local seasonality, fishing, livestock raising, and the presence of exotic species, affects the ecological stability of native populations, especially rare species such as D. cimex and U. concentricus, with only two occurrence records. Thus, the present study confirmed the data from previous investigations and mapped, for the first time, the malacofauna found in Barão de Melgaço, Poconé, and Santo Antônio do Leverger. This study, therefore, increases the knowledge on the invasive freshwater malacofauna of Pantanal northern in Mato Grosso, highlighting the occurrence of ecological exotic species (C. fluminea and M. tuberculata) and medical and veterinary interest, as M. tuberculata, to support actions and studies on biodiversity conservation and human and wildlife health.