INTRODUCTION

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the document entitled “WHO recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience”, contemplating the prevention and reduce perineal trauma, this being relevant in the intrapartum period.1

Perineal trauma is an injury that occurs in the perineum during vaginal delivery, which can compromise other anatomical structures of the pelvic floor. It can be produced by perineal laceration, representing spontaneous rupture of the tissue during the passage of the cephalic pole of the newborn, and/or by episiotomy, a surgical incision performed by the professional.2 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers that the expected frequency inherent to some degree of laceration in vaginal delivery varies from 53% to 73%.2

Perineal lacerations are classified into degree I, II, III or IV, and although degree III and IV are less prevalent, they can further compromise the tissue plane, structures and functions of the pelvic floor. They can trigger sexual disorders (chronic pain and dyspareunia), gynecological disorders (discomfort during gynecological examination), urinary disorders (urinary incontinence), as well as coloproctological and pelvic organ prolapse disorders, requiring multidisciplinary therapeutic care.3),(4

Perineal lacerations are multifactorial, highlighting their association with maternal characteristics (age between 27 and 30 years, primiparity and gestational age ≥ 42 weeks), characteristics related to the fetus/newborn (head circumference > 35 cm),4 obstetric characteristics and those related to the procedures and interventions of the obstetric team during labor (second stage of labor lasting more than two hours, instrumental vaginal birth, use of oxytocin and induced labor).1),(4 In relation to degrees III and IV, the ACOG considers the main factors associated with the outcome to be the newborn’s weight above 4 kg, shoulder dystocia, type of fetal occiput posterior position, women of Asian ethnicity, primiparity, prolonged expulsion stage and instrumental delivery associated or not with episiotomy.2

In the literature, data on the prevalence of perineal laceration are divergent,2 in addition we did not find articles that jointly analyze associated factors and prevalence in the Brazilian context. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the prevalence of perineal laceration based on the self-reported perception of postpartum women and to analyze factors associated with its occurrence in Brazil.

METHODS

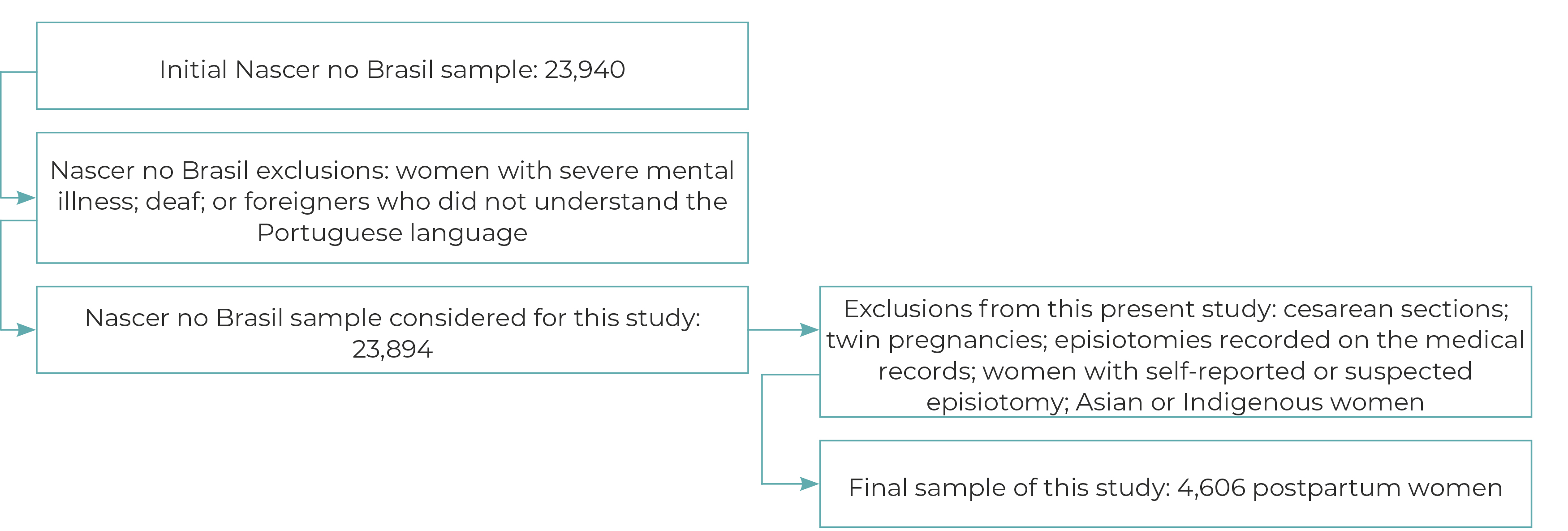

This was a cross-sectional study using data from the national survey entitled “Nascer no Brasil: Inquérito Nacional sobre Parto e Nascimento” (Born in Brazil: National survey on Childbirth and Birth, coordinated by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), conducted between between 2011 and 2012, and organized into three stages. In the first stage, 266 hospitals were selected, being public, private or a mixture of both, with 500 or more births/year in the Brazilian macro-regions, both in state capitals and interior regions. In the second stage, seven days were calculated to obtain a sample of 90 postpartum women per hospital. Finally, in the third stage, postpartum women were selected until the final sample of 23,894 postpartum women was obtained. Other details about the survey can be found in the study by Leal et al.5 Eligible women were those who gave birth to a live newborn or stillborn weighing ≥ 500 g and/or gestational age ≥ 22 weeks, excluding those with severe mental disorder, deaf or foreigners who did not understand the Portuguese language.5

The exclusion criteria used by this study were having had a cesarean section, having twins, having a medical record showing performance of episiotomy, self-reporting performance or suspected performance of episiotomy and/or being Asian or Indigenous. The data we analyzed were obtained from the women’s medical records, questionnaires and/or prenatal cards. The dependent variable was the women’s self-reported perception of perineal laceration, obtained by means of the following question as part of the questionnaire administered with the women: Do you know what your perineum (vagina) was like after giving birth? The answer options were as follows: it wasn’t torn, it wasn’t cut and there were no stitches; it tore a little, but didn’t need stitches; I didn’t get stitches, but I don’t know if it was torn; it was torn and I had stitches; they cut and stitched it; I had stitches, but I don’t know if it tore or if the doctor cut it; unable to inform. Women who replied “it tore a little, but didn’t need stitches” and “it was tore and I had stitches” were classified as having perineal laceration according to their perception. The remaining women were classified as not having perineal laceration according to their perception, and the reply “I had stitches, but I don’t know if it tore or if the doctor cut it” was not considered to indicate laceration because of the possibility of including women who underwent episiotomy, as this was an exclusion criteria in this study.

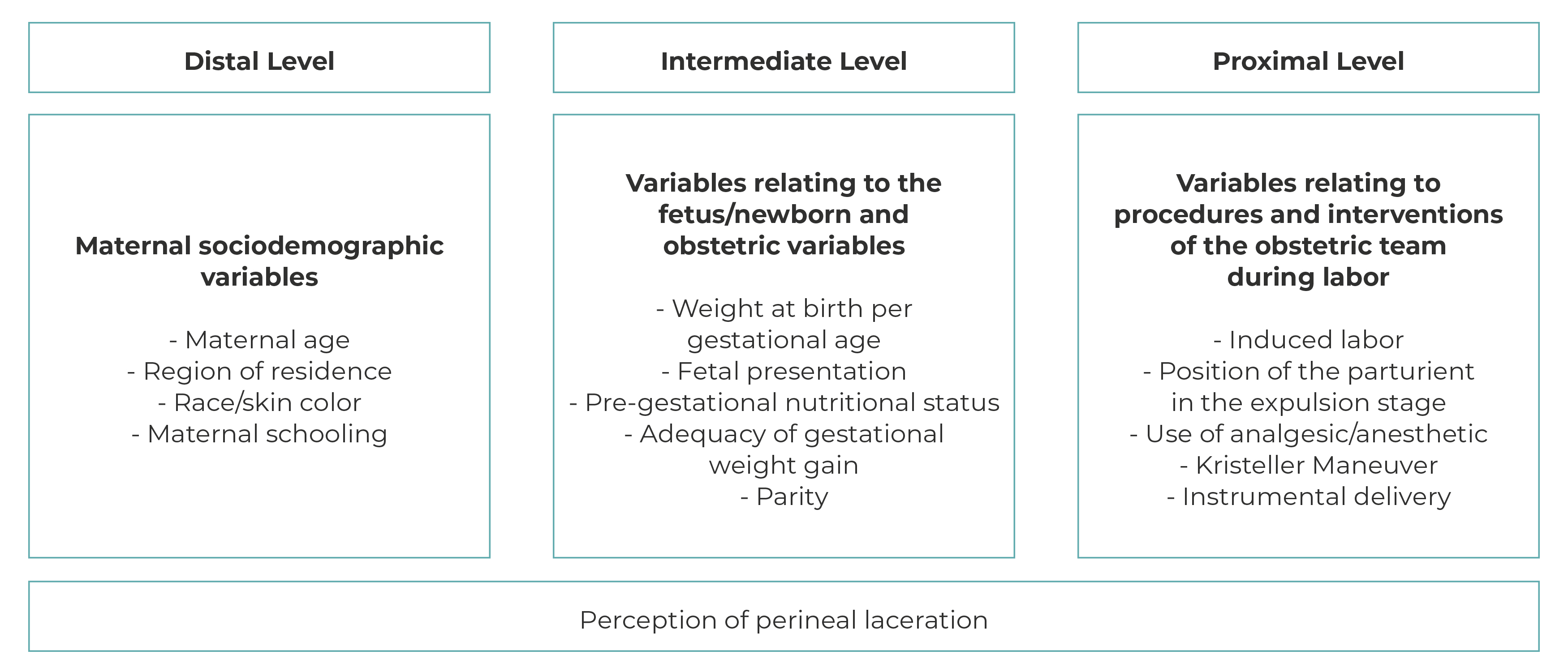

We considered the following independent variables: maternal sociodemographic characteristics, fetus/newborn characteristics, obstetric characteristics and the procedures and interventions of the obstetric team during labor, organized into distal, intermediate and proximal hierarchical levels (Figure 1).

On the distal level, maternal sociodemographic aspects obtained from the postpartum women’s questionnaire were included: maternal age range in years (12-19; ≥ 20-34; ≥ 35); Brazilian region of residence (North; Northeast; Southeast; South; Midwest); race/skin color (White; Black; mixed race; Asian; Indigenous); schooling (incomplete elementary education; complete elementary education; incomplete high school education; complete high school education; complete higher education and above). In view of the small sample size regarding Asian and Indigenous race/skin color, we decided to exclude this group from the analyses.

On the intermediate level, birth weight for gestational age was classified based on the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st), whereby newborns were classified as small for gestational age (below the 10th percentile), appropriate for gestational age, between the 10th and 90th percentile), and large for gestational age (above the 90th percentile).6) Fetal presentation was categorized as cephalic, breech or shoulder.5) These data were collected from medical records.

With regard to obstetric characteristics, we considered pre-gestational nutritional status (low weight: < 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: ≥ 18.5 to ≤ 24.9 kg/m2; overweight: ≥ 25 to ≤ 29.9 kg/m2; obese: ≥ 30 kg/m2),7) adequacy of gestational weight gain (insufficient; adequate; excessive) and parity (primipara; multipara). In order to calculate adequacy of gestational weight gain, we took weight at the end of pregnancy or weight at the last medical consultation, less pre-gestational weight, both self-reported or collected from the prenatal card, whereby adequacy was corrected for gestational age.5

On the proximal level, we considered variables related to obstetric team management and intervention during labor: induced labor (no; yes); position of the parturient in the expulsion stage (vertical; horizontal); analgesic/anesthetic use (no; yes); Kristeller maneuver (no; yes); instrumental delivery (forceps/vacuum cup: no; yes). These data were collected from medical records.

The variables were organized in a theoretical conceptual framework by level of proximity to the outcome, including predictive factors for perineal laceration based on criteria defined by the ACOG and Tavares et al.2),(4

The data were input to the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) REDCap application and analyzed using Stata 13 software. Prevalence ratios were estimated by adjusting Poisson regression models. In addition to the analysis model for each study covariate, the covariates of the three levels that were significant (p-value < 0.05) were kept in the final adjusted model. The analyses were performed using the Stata survey module because data were obtained through complex sampling.

The main study was approved by the Fiocruz Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública (ENSP) Research Ethics Committee (Opinion No. 92/10; Certificate of Submission for Ethical Appraisal [Certificado de Apresentação para Apreciação Ética - CAAE]: No. 0096.0.031.000-10), in keeping with the free and informed consent form. Our study was submitted to the Instituto Nacional de Saúde da Mulher, da Criança e do Adolescente Fernandes Figueira Research Ethics Committee and approved as per Opinion No. 5.486.223/CAAE: 57347922.2.0000.5269, in accordance with National Health Council Resolution No. 466/2012.

RESULTS

Of the total number of women who participated in the larger study (23,894), 19,288 postpartum women were excluded for the following reasons: 12,409 women who had cesarean sections, 43 with twin pregnancies, 5,683 with a record of episiotomy in their medical records, 1,063 with self-reported or suspected episiotomy and 90 of Asian or Indigenous race/skin color (Figure 2), so that our study consisted of 4,606 women who had recently given birth vaginally, 49.5% (95%CI 46.1;42.9) of whom self-reported perineal laceration.

Of the postpartum women evaluated, 71.5% were aged between 20 and 34 years, 39.7% lived in the Southeast region of Brazil, 64.3% were of mixed race/skin color, 40.3% had incomplete elementary education.

Regarding the characteristics of the fetus, 99.0% had cephalic presentation and 79.8% were classified as appropriate for gestational age. Regarding obstetric characteristics, 73% were multiparous, 34.7% had excessive gestational weight gain. Regarding obstetric team procedures and interventions, 96.4% of the postpartum women did not receive analgesia/anesthesia and 24.3% underwent the Kristeller maneuver (Table 1).

Table 1 ‒ Maternal sociodemographic profile, relating to the fetus/newborn, obstetrics and procedures and interventions of the obstetric team during labor, Brazil, 2011-2012

| Variables | na | % |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||

| 12-19 | 831 | 19.0 |

| 20-34 | 3,315 | 71.5 |

| 35 or over | 459 | 9.5 |

| Region of residence | ||

| North | 743 | 12.8 |

| Northeast | 1,538 | 33.3 |

| Southeast | 1,325 | 39.7 |

| South | 681 | 9.7 |

| Midwest | 319 | 4.6 |

| Race/skin color | ||

| White | 1,112 | 24.7 |

| Black | 478 | 11.0 |

| Mixed race | 3,014 | 64.3 |

| Maternal schooling | ||

| Incomplete elementary education | 1,967 | 40.3 |

| Complete elementary/incomplete high school education | 1,265 | 29.2 |

| Complete high school education | 1,268 | 28.6 |

| Complete higher education and above | 106 | 1.9 |

| Weight at birth per gestational age | ||

| Small for gestational age | 367 | 7.9 |

| Appropriate for gestational age | 3,606 | 79.8 |

| Large for gestational age | 619 | 12.3 |

| Fetal presentation | ||

| Cephalic | 4,121 | 99.0 |

| Breech | 39 | 1.1 |

| Adequacy of gestational weight gain | ||

| Insufficient | 1,538 | 32.6 |

| Adequate | 1,490 | 32.7 |

| Excessive | 1,578 | 34.7 |

| Pre-gestational nutritional status | ||

| Low weight | 428 | 9.1 |

| Normal weight | 2,780 | 61.2 |

| Overweight | 1,028 | 22.1 |

| Obesity | 370 | 7.6 |

| Parity | ||

| Primipara | 1,108 | 27.1 |

| Multipara | 3,498 | 73,0 |

| Induced labor | ||

| No | 3,989 | 85.4 |

| Yes | 617 | 14.6 |

| Position of the parturient during the expulsion period | ||

| Horizontal | 4,782 | 89.3 |

| Vertical | 575 | 10.7 |

| Use of analgesic/anesthetic | ||

| No | 4,374 | 96.4 |

| Yes | 163 | 3.6 |

| Kristeller Maneuver | ||

| No | 3,411 | 75.7 |

| Yes | 1,195 | 24.3 |

| Instrumental delivery | ||

| No | 4,551 | 99.0 |

| Yes | 55 | 1.0 |

a) n: Unweighted sample size.

In the bivariate analysis, the following distal level variables were associated with the outcome: maternal age between 12 and 19 years (PR = 1.27; 95%CI 1.12;1.43), living in the Northern region (PR = 0.59; 95%CI 0.45;0.76), Southern region (PR = 0.84; 95%CI 0.73;0.97), Northeast region (PR = 0.76; 95%CI 0.66;0.88), Black race/skin color (PR = 0.81; 95%CI 0.70;0.95), mixed race/skin color (PR = 0.83; 95%CI 0.76;0.90), incomplete elementary school education (PR = 0.56; 95%CI 0.47;0.69) and complete elementary school education (PR = 0.78; 95%CI 0.65;0.93). On the intermediate level, the variables associated with laceration were: having had a baby that was small for gestational age (PR = 0.75; 95%CI 0.61;0.92), breech fetal presentation (PR = 0.40; 95%CI 0.17;0.90), having had insufficient gestational weight gain (PR = 0.89; 95%CI 0.80;0.99) and being primipara (PR = 3.21; 95%CI 2 .40;4.30). On the proximal level, the following were associated: induced labor (PR = 1.13; 95%CI 1.02;1.25), use of analgesia (PR = 1.30; 95%CI 1.07;1.58), Kristeller maneuver (PR = 1.22; 95%CI 1.10;1.36) and use of forceps/vacuum cup (PR = 0.62; 95%CI 0.52;0.75) (Table 2).

Table 2 ‒ Bivariate analysis of maternal sociodemographic factors, relating to the fetus/newborn, obstetrics and procedures and interventions of the obstetric team during labor, Brazil, 2011-2012

| Variables | Perineal laceration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | PRa | 95%CIb | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Distal level | ||||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| 12-19 | 407 (15.0) | 615 (23.3) | 1.27 | 1.12;1.43 |

| 20-34 | 2,009 (74.0) | 1,815 (68.7) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| 35 or over | 298 (11.0) | 210 (8.0) | 0.87 | 0.75;1.01 |

| Region of residence | ||||

| North | 456 (16.8) | 236 (8.9) | 0.59 | 0.45;0.76 |

| Northeast | 968 (36.3) | 791 (30.0) | 0.76 | 0.66;0.88 |

| Southeast | 897 (33.0) | 1,226 (48.5) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| South | 268 (9.9) | 255 (9.7) | 0.84 | 0.73;0.97 |

| Midwest | 111 (4.1) | 131 (5.0) | 0.93 | 0.78;1.10 |

| Race/skin color | ||||

| White | 563 (20.7) | 734 (27.8) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Black | 311 (11.4) | 268 (10.2) | 0.81 | 0.70;0.95 |

| Mixed race | 1,784 (65.7) | 1,598 (60.6) | 0.83 | 0.76;0.90 |

| Maternal schooling | ||||

| Incomplete elementary education | 1,341 (49.3) | 821 (31.1) | 0.56 | 0.47;0.69 |

| Complete elementary/incomplete high school education | 750 (27.6) | 817 (30.9) | 0.78 | 0.65;0.93 |

| Complete high school education | 592 (21.8) | 933 (35.3) | 0.91 | 0.76;1.09 |

| Complete higher education and above | 35 (1.3) | 69 (2.6) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Intermediate level | ||||

| Weight at birth per gestational age | ||||

| Small for gestational age | 258 (9.5) | 160 (6.1) | 0.75 | 0.61;0.92 |

| Appropriate for gestational age | 2,112 (78.0) | 2,159 (81.8) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Large for gestational age | 337 (12.4 | 320 (12.1) | 0.96 | 0.83;1.11 |

| Fetal presentation | ||||

| Cephalic | 2,430 (98.3) | 2,409 (99.6) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Breech | 42 (1.7) | 10 (0.4) | 0.40 | 0.17;0.90 |

| Pre-gestational nutritional status | ||||

| Low weight | 230 (8.5) | 257 (9.7) | 1.03 | 0.89;1.20 |

| Normal weight | 1,640 (60.3) | 1,646 (62.4) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Overweight | 630 (23.2) | 543 (20.6) | 0.91 | 0.82;1.01 |

| Obesity | 219 (8.0) | 194 (7.3) | 0.91 | 0.78;1.07 |

| Adequacy of gestational weight gain | ||||

| Insufficient | 965 (35.5) | 776 (29.4) | 0.89 | 0.80;0.99 |

| Adequate | 890 (32.7) | 867 (32.8) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Excessive | 863 (31.7) | 997 (37.8) | 1.20 | 1.08;1.33 |

| Parity | ||||

| Primipara | 448 (16.5) | 1,005 (38.1) | 3.21 | 2.40;4.30 |

| Multipara | 2,270 (83.5) | 1,635 (61.9) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Proximal level | ||||

| Induced labor | ||||

| No | 2,362 (86.9) | 2,214 (83.9) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Yes | 355 (13.1) | 426 (16.1) | 1.13 | 1.02;1.25 |

| Position of the parturient in the expulsion stage | ||||

| Horizontal | 2,427 (89.3) | 2,355 (89.2) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Vertical | 290 (10.7) | 285 (10.8) | 1.10 | 0.71;1.71 |

| Use of analgesic/anesthetic | ||||

| No | 2,604 (97.3) | 2,494 (95.3) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Yes | 72 (2.7) | 122 (4.7) | 1.30 | 1.07;1.58 |

| Kristeller Maneuver | ||||

| No | 2,168 (79.8) | 1,891 (71.6) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Yes | 550 (20.2) | 748 (28.4) | 1.22 | 1.10;1.36 |

| Instrumental delivery forceps/vacuum cup | ||||

| No | 2,705 (99.5) | 2,598 (98.4) | 1.00 | ‒c |

| Yes | 12 (0.5) | 41 (1.6) | 0.62 | 0.52;075 |

a) PR: Prevalence ratio; b) 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; c) feature (‒): Information not applicable.

In the multivariate analysis, the followed raised the proportion of the outcome: maternal age between 12 and 19 years (PR = 1.12; 95%CI 1.02;1.25), primiparity (PR = 1.47; 95%CI 1.33;1.63), excessive gestational weight gain (PR = 1.17; 95%CI 1.07;1.29) and Kristeller maneuver (PR = 1.18; 95%CI 1.08;1.29). While living in the Northeast region (PR = 0.84; 95%CI 0.74;0.95) and Northern region (PR = 0.65; 95%CI 0.52;0.81), having incomplete elementary education (PR = 0.67; 95%CI 0.55;0.83), having had a baby that was small for gestational age (PR = 0.77; 95%CI 0.64;0.93) and having gained insufficient gestational weight (PR = 0.88; 95%CI 0.81;0.96) reduced the proportion of the outcome (Table 3).

Table 3 ‒ Multivariate analysis of maternal sociodemographic factors, relating to the fetus/newborn, obstetrics and procedures and interventions of the obstetric team during labor, Brazil 2011-2012

| Model 1 Distal variables | Model 2 Distal and intermediate variables | Model 3 Distal, intermediate and proximal variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | PRa | 95%CIb | PRa | 95%CIb | PRa | 95%CIb |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||

| 12-19 | 1.36 | 1.22;1.51 | 1.14 | 1.02;1.27 | 1.12 | 1.02;1.25 |

| 20-34 | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| 35 or over | 0.91 | 0.79;1.04 | 0.98 | 0.84;1.14 | 1.00 | 0.86;1.16 |

| Race/skin color | ||||||

| White | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Black | 0.90 | 0.78;1.03 | 0.89 | 0.78;1.01 | 0.89 | 0.78;1.01 |

| Mixed race | 0.94 | 0.86;1.02 | 0.93 | 0.84;1.03 | 0.93 | 0.85;1.03 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| North | 0.64 | 0.51;0.81 | 0.67 | 0.54;0.83 | 0.67 | 0.52;0.81 |

| Northeast | 0.86 | 0.75;0.98 | 0.87 | 0.77;0.99 | 0.87 | 0.74;0.95 |

| Southeast | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| South | 0.87 | 0.77;0.99 | 0.89 | 0.78;1.02 | 0.90 | 0.78;1.03 |

| Midwest | 0.96 | 0.82;1.12 | 1.03 | 0.87;1.21 | 0.99 | 0.85;1.16 |

| Maternal schooling | ||||||

| Incomplete elementary education | 0.57 | 0.47;0.70 | 0.68 | 0.56;0.84 | 0.67 | 0.55;0.83 |

| Complete elementary education | 0.73 | 0.61;0.88 | 0.86 | 0.71;1.05 | 0.89 | 0.73;1.09 |

| Complete high school education | 0.88 | 0.73;1.07 | 0.96 | 0.80;1.16 | 1.00 | 0.82;1.22 |

| Complete higher education and above | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Weight at birth per gestational age | ||||||

| Small for gestational age | 0.76 | 0.62;0.93 | 0.77 | 0.64;0.93 | ||

| Appropriate for gestational age | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Large for gestational age | 1.13 | 0.97;1.30 | 1.11 | 0.96;1.28 | ||

| Fetal presentation | ||||||

| Cephalic | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Breech | 0.50 | 0.23;1.09 | 0.50 | 0.21;1.20 | ||

| Adequacy of gestational weight gain | ||||||

| Insufficient | 0.89 | 0.81;0.97 | 0.88 | 0.81;0.96 | ||

| Adequate | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Excessive | 1.18 | 1.07;1.31 | 1.17 | 1.07;1.29 | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primipara | 1.50 | 1.36;1.65 | 1.47 | 1.33;1.63 | ||

| Multipara | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Induced labor | ||||||

| No | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 0.94 | 0.85;1.04 | ||||

| Parturient position during the expulsion period | ||||||

| Horizontal | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Vertical | 1.02 | 0.86;1.21 | ||||

| Use of analgesic and anesthetic | ||||||

| No | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.86;1.22 | ||||

| Kristeller Maneuver | ||||||

| No | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 1.18 | 1.08;1.30 | ||||

| Instrumental delivery forceps/vacuum cup | ||||||

| No | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 1.00 | ‒ |

| Yes | 1.14 | 0,93;1,39 | ||||

a) PR: Prevalence ratio; b) 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Being an adolescent or primipara woman, having had excessive gestational weight gain and having undergone a Kristeller maneuver during childbirth were associated with self-reported perception of perineal laceration. While living in the North or Northeast region, having incomplete elementary education, having a baby that was small for gestational age and having insufficient gestational weight gain, reduced the proportion of the outcome.

Although the prevalence of perineal laceration found in this study was different from that reported in other studies,8),(9 it was similar to that estimated by the ACOG.2

In their analysis of the medical records of a cohort of 935 parturient women who did not undergo episiotomy and gave birth at a university hospital in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, between 2013 and 2014, Monteiro et al. found that 78.2% of those women suffered some degree of perineal laceration.9 Likewise, a prospective analysis of 222 vaginal births without episiotomy in the city of Recife, Pernambuco, between 2012 and 2013, found that the prevalence of perineal laceration was 79.7%, whereby the authors suggested that the high occurrence of the outcome could be associated with interventional care of health teams, even in a humanized context.7) On the other hand, a cross-sectional study carried out on 3,255 parturient women in Iran,8 in 2015, found a prevalence of laceration (16%) lower than that found in the aforementioned Brazilian studies and in ACOG studies.2 The authors highlighted professional training as a measure for improving women’s care and quality of life.8

With regard to the distal level (maternal sociodemographic factors), maternal age, region of residence and maternal schooling were associated with the outcome.

The analysis showed that the proportion of perineal laceration was 14% higher among adolescents (12 and 19 years old) compared to adult women. These results are in keeping with the results of a retrospective study carried out in Romania with 1,498 parturient women, of whom 298 were adolescents, between 2020 and 2021, which found 89% higher odds of laceration among adolescents when compared to adults.10) Greater frequency of perineal laceration during adolescence can be attributed to the immaturity of pelvic bone growth and muscle development, leading to a reduction in the internal diameters of the pelvis and the muscular strength of the pelvic floor, increasing the risk of adverse birth outcomes, such as perineal laceration.11

We found that living in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil was associated with lower prevalence of laceration based on the perception of the postpartum women. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in partnership with the Network for the Humanization of Child Delivery and Birth (Rede pela Humanização do Parto e Nascimento), evaluated perinatal care in Brazil, based on Ministry of Health data on deliveries carried out between 2000 and 2017, and found inequalities in the availability and quality of obstetric care nationwide.12 Based on this survey, UNICEF concluded that although there was an increase in access to prenatal care in primary care and that Rede Cegonha network had been implemented during this period, there was less prenatal care available in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, suggesting the inadequate organization of obstetric care associated with the poorer living conditions in those regions.12),(13

However, the results we found, regarding the lower prevalence of the event among postpartum women living in the North and Northeast regions and among those with a lower level of education, must be evaluated with caution, since these factors can influence the perception of care and health status of this population.

Although obstetric interventions associated with pain, fear, tension and anxiety may favor the occurrence of adverse birth outcomes, these outcomes may be less perceived in vulnerable contexts.14 A meta-analysis carried out in Ethiopia in 2018, which included 20 studies and involved a sample of 13,744 pregnant women, estimated the effect of maternal schooling on knowledge and preparation for childbirth and decision-making capacity in the face of obstetric complications, and noted that pregnant women with higher levels of education had greater knowledge and preparation for the childbirth process.14

According to the WHO 2018 Recommendations, a higher level of maternal schooling can promote better understanding and adherence to prenatal and labor guidelines.1

Among the intermediate level variables (fetus/newborn characteristics and obstetric characteristics), adequacy of birth weight in relation to gestational age, maternal gestational weight gain and parity were associated with the occurrence of perceived perineal laceration.

According to the literature, macrosomia (newborn weight ≥ 4,000 g) increases the probability of dystocic births and may require instrumental delivery, increasing the risk of perineal laceration.15 In our study, delivery of newborns who were small for gestational age was a protective factor regarding perception of perineal laceration. These results agree with data from a study conducted in Sweden with 212,101 newborns, between 2006 and 2015, which found lower odds of serious perineal lacerations among mothers of those newborns.16 As such, lower biometric measurements (weight and length) partially justify these results, as they reduce mechanical challenges in relation to the path of the birth canal and perineum.15)-(17

Still in relation to the intermediate level variables, a higher proportion of the outcome was observed among primiparous women. These results are in keeping with the meta-analysis conducted by Wilson & Homer,18 involving 12 studies published between 2013 and 2018, and a sample of 515,161 postpartum women, which showed 3.2 times higher odds of laceration among primiparous women when compared to multiparous women.18 Confirming these results, cross-sectional study with data from medical records of 421 postpartum women with vaginal birth in Ceará, between 2016 and 2018, it found a higher percentage of lacerations among primiparous women (53.4%) when compared to multiparous women (46.6%).19 Greater risk of perineal laceration among primiparous women has been explained by the parturient’s lack of knowledge about the functionality and self-control of the perivaginal muscles during childbirth, associated with the fear-anxiety-pain cycle, leading to excessive activation of muscles that have not yet experienced elasticity and distensibility arising when there have been previous births.17

In addition to these factors, some interventions carried out by healthcare teams, such as restricting mobility and keeping the parturient in a lithotomy position, may favor the occurrence of perineal lacerations in primiparous women.18

Although it is not possible to avoid primiparity, it is possible to guide procedures, as per the WHO 2018 Recommendations, such as performing perineal massage from the 35th prenatal week onwards, in order to prevent more serious lacerations.1

A systematic review with meta-analysis of 50 clinical trials, involving 17,221 pregnant women, showed that perineal massage was effective in preserving the perineum, reducing the risk of perineal laceration.20 It also highlighted that the influence of educational activities during prenatal care can inform pregnant women and encourage them to adopt different positions during labor, reducing the risk of interventions and perineal trauma.20

Regarding maternal characteristics, insufficient gestational weight gain was a protective factor for the outcome, while excessive weight gain increased the prevalence of the outcome. Maternal gestational weight can be predictive of biometric changes in the fetus/newborn, which can result in dystocic births, predisposing to perineal laceration.15 It is noteworthy that excessive gestational weight gain predisposes to macrosomia and consequently to perineal laceration.21

A retrospective study of 4,127 births that occurred in Milan, Italy, between 2016 and 2020, found that postpartum women with excess gestational weight gain and mothers of large for gestational age newborns had 2.04 times greater odds of severe perineal lacerations when compared to women with insufficient weight gain and small for gestational age newborns, recommending control of gestational weight in order to reduce adverse birth outcomes.21

With regard to the proximal level variables, relating to health team procedures and interventions in childbirth care, the Kristeller maneuver was the only variable statistically associated with the outcome. A study with similar results, carried out in Peru by Becerra-Chauca & Failoc-Rojas, in 2016, found that among 116 births with Kristeller maneuver intervention, perineal lacerations occurred in 32.8% of them.22 The maneuver promotes intense downward pressure towards the pelvic floor, favoring association with instrumental delivery and, consequently, perineal laceration.1

It should be highlighted there have been WHO recommendations to eliminate this maneuver and similar interventions since 1996,1 and this recommendation was incorporated into Brazilian Ministry of Health guidelines in Brazil in 2017. The Kristeller maneuver was proscribed in the WHO global birth guidelines in 2018.1),(23 Notwithstanding, in the Brazilian birth guidelines published by the Ministry of Health in 2022, there is no mention of support or ratification of the current WHO proscription.24

In our study, data relating to perineal laceration extracted from medical records showed a high degree of incompleteness, with this event being recorded in only 25% of the parturient women studied, this being a much lower prevalence rate than that obtained from self-reporting. According to Correa et al.,25) data from medical records need to have sufficient completeness, quality and reliability in order to adequately represent the reality studied, contributing to the planning of health care strategies and related policies.25

A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by the WHO, with 74 review studies published between 2004 and 2016, involving 300,000 vaginal births, occurring in 41 countries, examined laceration rates in low - and middle-income countries, including Brazil.26 According to that study, rates of perineal trauma, indicators of health care quality, were above 70% in low- and middle-income countries and suggested underreporting. The study concluded that there is heterogeneity in care and professional practices and notifications, as well as difficulties in collecting this data from birth records, resulting in a lack of knowledge of the true parameters.26

It is also noteworthy that the majority of articles do not evaluate women’s perception of interventions during childbirth. Health service user perception allows evaluation of public health policies and provides support for their improvement.20 In the 2016 Cochrane meta-analysis review, covering 20 selected studies, with data from 15,181 women with perineal laceration, only one study evaluated their perception.

There are gaps regarding women’s opinions and perceptions regarding perineal trauma, beyond the simple investigation of satisfaction with birth outcomes.27 Roper et al. (2020)28) evaluated and compared 13 guidelines on perineal trauma and their recommendations, published between 2008 and 2019, using the validated instrument called Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II, and suggested that the formulation of guidelines should include interested parties, such as those affected by the problem, taking their opinions into consideration as relevant elements in the process.28

Therefore, although self-reporting does not constitute an accurate source for measuring the outcome, especially in areas with lower socioeconomic and educational levels, the high level of incompleteness and underreporting of the event in medical records, found in this study, guided the decision to use self-reported perception of parturient women as a source of information. Information on other factors that could influence the estimate of the event, such as previous perineal trauma, dystocia, head circumference, was not collected in the main study and is another limitation of our study.

Although the data used in this study were collected more than a decade ago, between 2011 and 2012, they are national in scope and included women cared for in public and private services, serving as a basis for comparative analyses on obstetric care in future studies, such as the 2022-2023 Nascer no Brasil Survey.

Based on the results found, the need to adopt recommendations and practices aimed at preventing perineal laceration in routine prenatal care and childbirth is confirmed. Actions aimed at training, attitudes and improving health professional practices and procedures and promoting interdisciplinary assistance in humanized maternal care are needed.

texto em

texto em