Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2337-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde v.25 n.2 Brasília abr./jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742016000200002

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Monitoring respiratory virus infection in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, 2011-2013

1Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Grupo de Pesquisa em Epidemiologia e Avaliação em Saúde, Belo Horizonte-MG, Brasil

2Fundação Hospitalar do Estado de Minas Gerais, Hospital Eduardo de Menezes, Belo Horizonte-MG, Brasil

OBJECTIVE:

to analyze the circulation of respiratory viruses in people living in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, and hospitalized in Belo Horizonte from 2011 to 2013.

METHODS:

this is a descriptive study of 5,158 patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; a comparison was made between the characteristics of confirmed cases and those of discarded cases or cases without swab samples.

RESULTS:

Influenza A virus accounted for half the isolated viruses, especially subtype A(H1N1)pdm09 among patients aged 20-59 years old, and subtype A(H3N2) in those aged 60 or over; the most frequently identified respiratory virus among children under five years old was respiratory syncytial virus (65.6%), followed by influenza A virus (21.2%); influenza virus circulated in all seasons of the year and its periods of greatest incidence were interspersed with those of higher Respiratory Syncytial Virus activity.

CONCLUSION:

monitoring respiratory viruses contributes to knowledge about periods of virus circulation and the adoption of specific control measures.

Key words: Hospitalization; Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; Respiratory Syncytial Viruses; Epidemiological Surveillance; Epidemiology, Descriptive.

Introduction

Acute respiratory diseases are responsible for most part of hospitalizations in developed countries and most of these infections are viral (80%).1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly eight million children under the age of five died in 2008 due to acute lower respiratory tract infections (ALRTI).2

The influenza and parainfluenza viruses are important etiologic agents of these infections.3 Among children under five years old, the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus are the most commonly involved in ALRTI cases. Not only are they associated with acute episodes, but also with worse symptoms in patients with chronic lung disease and young children.4,5 Studies on children in this age group indicate the rhinovirus as the most frequent (30%), followed by the RSV (24 to 28%), influenza virus (10%), parainfluenza (6%) and adenovirus (4%).6,7

Respiratory diseases caused by the influenza virus may be responsible for up to 64% of viral pneumonia in the society and its complication reflects in a significant number of hospitalizations in Brazil.3,8,9 WHO estimates that about one billion people are infected by the influenza virus every year, and in epidemic years the disease affects approximately 15% of the population.10,11 In 2009 - year of the pandemic of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus -, especially in Brazil, the mortality rate due to influenza A was 5.8%, and the incidence was 14.5/100 thousand inhabitants.12

The increase in hospitalizations and outpatient care due to acute respiratory infections may vary depending on the region of the country, climate and seasonality, hence the importance of knowing and monitoring its epidemiological profile in order to set priorities of human and financial resources allocation.13 A sentinel surveillance of respiratory viruses is held in Brazil since the year 2000. This surveillance monitors the strains of influenza virus that have been circulating in the five Brazilian regions by collecting nasopharyngeal secretions of outpatients with influenza syndrome (ILI). According to a study on sentinel surveillance of ILI in Brazil in the period 2000-2010, about three million patients with acute respiratory infection were assisted in sentinel units: 54% of those patients were under 15 years old and 1% had nasopharyngeal secretions samples collected.14

In 2011, the Brazilian Ministry of Health began an intensified surveillance of respiratory viruses in patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Belo Horizonte was the first city to apply this strategy. SARS surveillance is intended to be global so it can monitor the incidence of respiratory viruses in the hospitalized population and its results can contribute to the annual vaccination strategy. The vaccine is the main mechanism for preventing influenza and its health complications.

The aim of this study was to analyze the circulation of respiratory viruses in people living in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, and hospitalized in that city in the period between 2011 and 2013.

Methods

This is a descriptive study of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte (RMBH) admitted or awaiting admission in hospitals or urgency/emergency public and private care units of Belo Horizonte, at the time of notification on the epidemiological surveillance municipal system, from January 2011 to December 2013.

In the period analyzed, Belo Horizonte had approximately 2.5 million inhabitants,15 65 hospitals (60% of public beds), eight emergency care units (UPA) and eight hospitals with epidemiological surveillance service (NUVEH). The other 38 municipalities of the metropolitan region accounted for three million inhabitants, and Belo Horizonte was their health care reference. Namely: Belo Vale, Betim, Bonfim, Brumadinho, Caeté, Confins, Contagem, Crucilândia, Esmeraldas, Florestal, Ibirité, Igarapé, Itabirito, Jaboticatubas, Juatuba, Lagoa Santa, Mariana, Mário Campos, Mateus Leme, Matozinhos, Moeda, Nova Lima, Nova União, Ouro Preto, Pedro Leopoldo, Piedade dos Gerais, Raposos, Ribeirão das Neves, Rio Acima, Rio Manso, Sabará, Santa Luzia, Santana do Riacho, São Joaquim de Bicas, São José da Lapa, Sarzedo, Taquaraçu de Minas and Vespasiano.

According to the recommendation of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, SARS cases are defined as all patients hospitalized with ILI of any age group and with signs/symptoms of dyspnea, oxygen saturation below 95% or respiratory distress.16 The patient with ILI is understood to be the individual who presents sudden fever, even if it is self-reported, and cough or sore throat and at least one of the following symptoms in the absence of specific diagnosis: headache, myalgia or arthralgia.16

Even in the absence of fever, the epidemiological surveillance team established that patients awaiting hospitalization should also be reported, as well as children under two months old and adults aged 60 years old or more. These cases should be evaluated and reported to the municipal surveillance by the doctors and nurses of the medical unit. Clinical specimens were collected through a nasopharyngeal swab from those patients that were in the first seven days of symptoms, and those admitted to intensive care units (ICU), as well as patients who died in any phase of the disease. Patients hospitalized with positive laboratory results for respiratory virus were chosen to be compared to patients with negative results or that did not have material collected.

The methods used were the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and/or indirect immunofluorescence (IIF). Meetings with the involved health professionals were held in the Municipal Health Department and at the health care units, to explain the importance of monitoring respiratory viruses, patients flow and sample collection. Every month, reports were produced with primary results of this surveillance.

In order to report and investigate cases, the epidemiological surveillance adopted a standard form with the following variables:

- sex;

- age in years (<5; 5 to 19; 20 to 39; 40 to 59; and ≥ 60 years);

- place of residence (Belo Horizonte; other municipalities of the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte);

- pregnant woman (yes; no)

- puerperal woman (yes; no)

- comorbidities - heart disease; diabetes; liver disease; neurological disease; lung disease; kidney disease; immunodeficiency; obesity; asthma; smoking; hemoglobinopathy; Down syndrome; chronic metabolic disease - (yes; no)

- use of antiviral drugs (yes; no)

- symptoms - fever; cough; dyspnea; respiratory distress; oxygen saturation below 95%; sore throat; myalgia -; and

- hospitalization in intensive care units - ICU - (yes; no).

The municipal epidemiological surveillance conducted the data collection through passive or active report. A health professional of the health care unit where the patient was assisted carried out the passive report: the case was reported by phone and a standard form of notification was filled out. The active search was carried out by daily checking all patients admitted or awaiting admission for acute respiratory disease on the information system of the Municipal Hospital Admissions Center. The epidemiological surveillance professional required the inpatient care unit to fill out the form. Once the form was filled out it was returned to the municipal epidemiological surveillance service for registering into the information service. The reports were registered on an information system called influenza-BH, and on the national routine system. The municipal epidemiological surveillance team was responsible for receiving the report and requesting the swab collection of respiratory secretions to the home care service team (HCS). The collection was made within 24 hours of the request, although the appropriate period for this procedure could be up to seven days after the beginning of symptoms. For hospitalized patients in ICU and deaths, the material was always collected. The statistical analysis of the study was performed with the SPSS(r) version 19.0 and 2010 Microsoft Excel(r). The Pearson chi-square test and the level of significance of 5% were adopted to compare proportions between confirmed, discarded and without swab samples cases.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais and by the Municipal Health Department of Belo Horizonte, CAAE No. 19790213.7.0000.5149.

Results

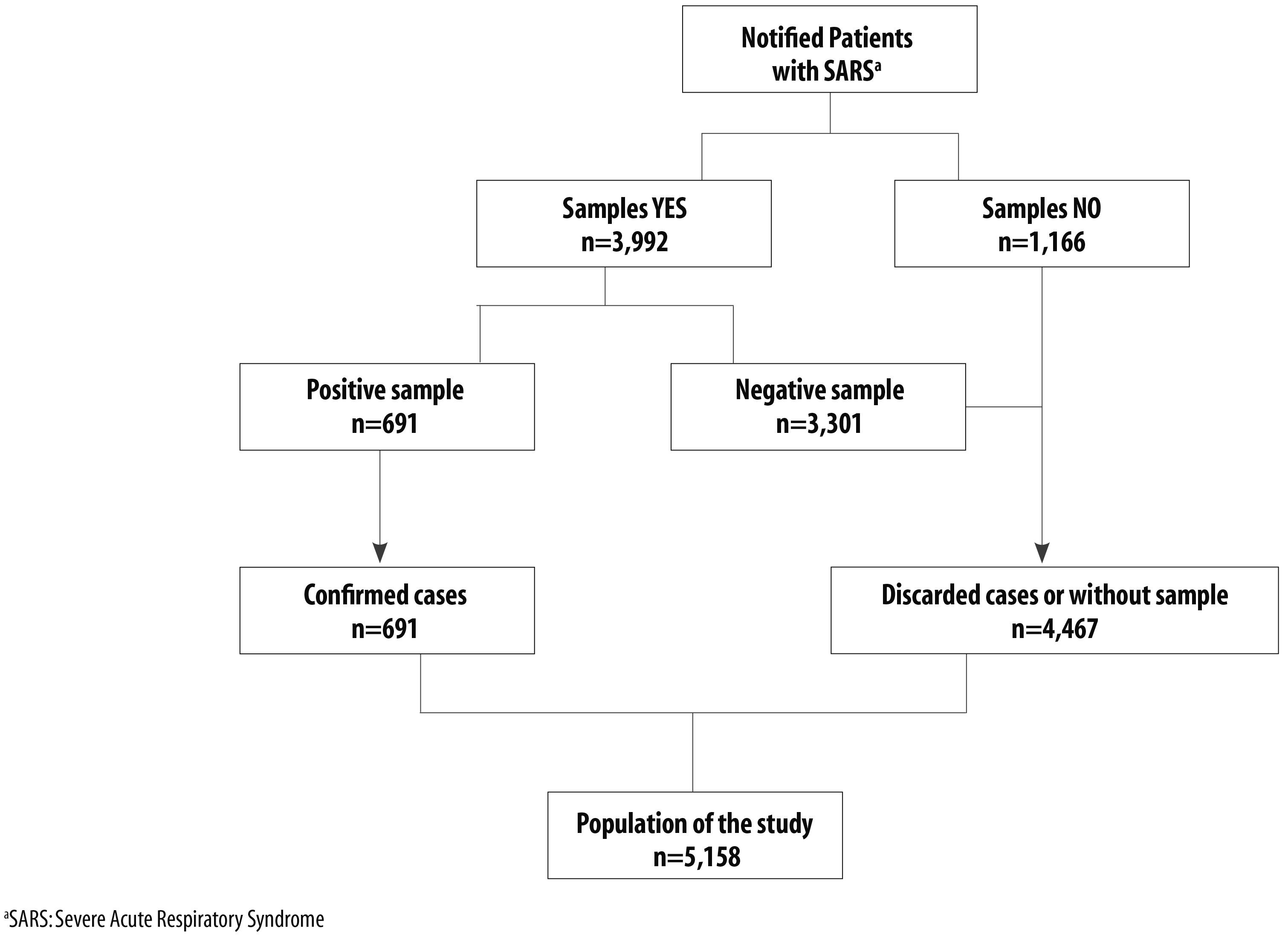

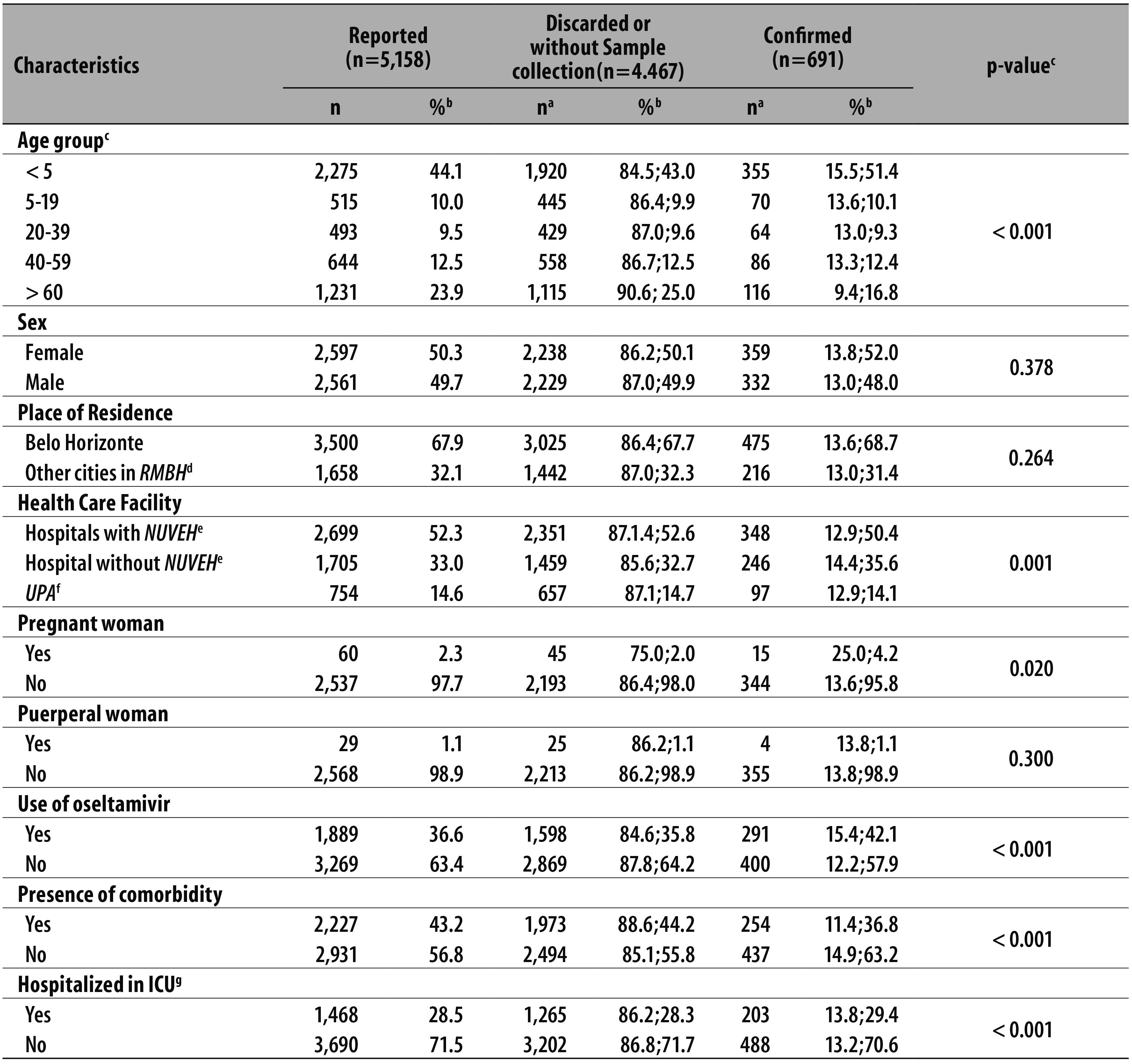

This study included all SARS reported cases from 2011 to 2013 (n=5,158). 68.8% of the individuals lived in Belo Horizonte and 31.4% in other municipalities of the metropolitan area (Figure 1). The laboratory material was collected in 77.4% of the reported cases (n=3,992) and 691 of the patients (17.3%) had positive results for at least one respiratory virus; 3 patients had double viral infection. Although the group of children under five years old was the one with the highest number of reported (n=2,265) and confirmed (n=355) cases, almost 30% of the individuals with positive results for respiratory virus were between 20 and 59 years old. There was no difference between the proportions of infected men and women. The groups of pregnant and puerperal women together represented less than 2% of the 2,597 reported women (50%), however the proportion of confirmed cases in these groups was 25% and approximately 15%, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1 - Flowchart of participants of the respiratory virus surveillance study in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2011 to 2013

Table 1 - Absolute and relative frequency of individual and clinical characteristics of reported patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome according to characteristics in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2011-2013

a) Calculation based on the total amount of notified cases

b) Calculation based on the total of cases in the column (notified, discarded or without sample collection, confirmed)

c) Pearson Chi-square

d) Metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte

e) Epidemiological Surveillance Service

f) Primary Health Care Service

g) Intensive Care Unit

The eight hospitals with epidemiological surveillance (NUVEH) were responsible for more than half of the reported (52.3%) and confirmed (50.4%) cases. The main reporting children's hospital in the city is also a NUVEH hospital. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) between confirmed cases and discarded cases or without sample collection for the following variables: age; use of antiviral drug; at least one comorbidity; and hospitalized in an ICU (Table 1).

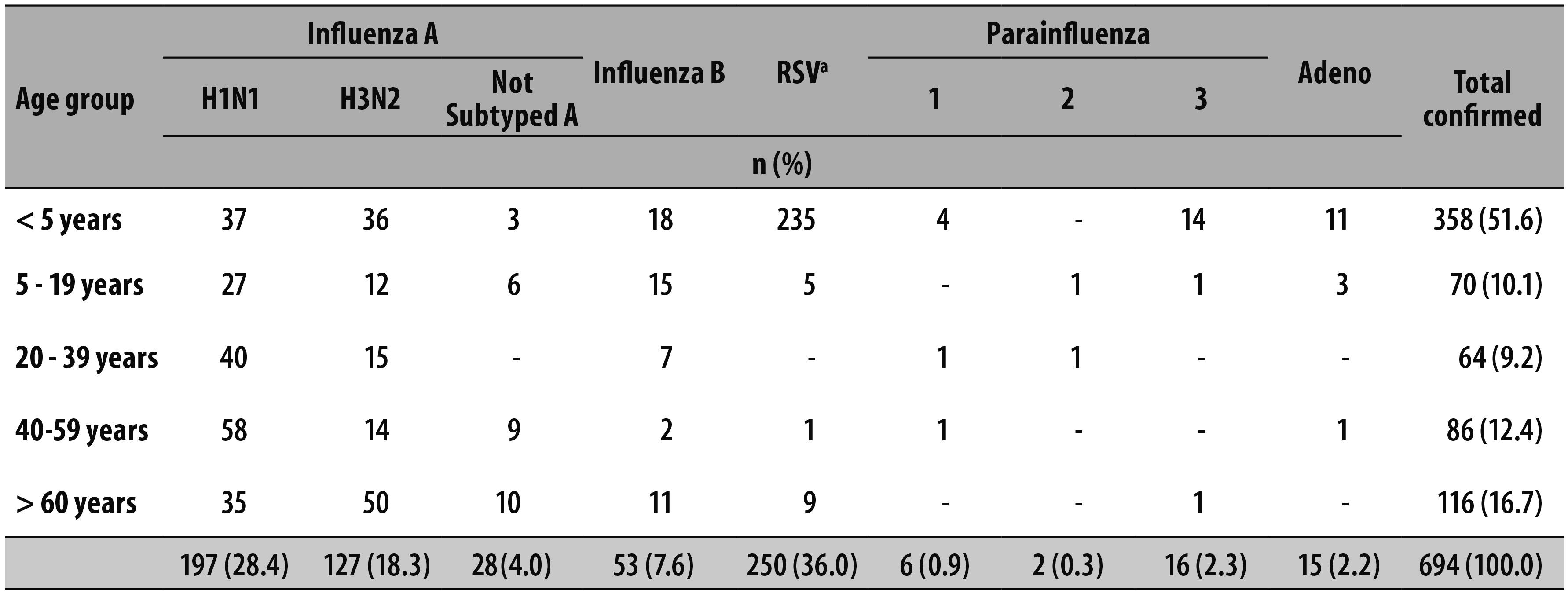

The influenza A virus (50.7%) was the most frequent of all isolated respiratory viruses and the subtype A (H1N1)pdm09 was identified in bigger proportions in adults. In the three selected years of the study, the RSV (36.0%) was the second isolated respiratory virus in the population living in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte and was identified in a bigger proportion in children under the age of five (94.0%) (Table 2). Among adults aged 60 years or more, the most frequent subtype was A(H3N2). Among children under five years old the most frequent virus was the RSV with 65.6%, followed by the A(H1N1), with 10.3% and A(H3N2) with 10.1%. Influenza virus circulated during all seasons of the year and its periods of major incidence were interspersed with those of higher RSV activity(Figure 2).

Table 2 - Absolute and relative frequency of respiratory virus according to age group, Belo Horizonte, 2011-2013

aRSV: respiratory syncytial virus

Figure 2 - Virus identified in samples of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome according to detection technique and month of notification in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2011-2013

The most frequent symptoms reported by patients with respiratory virus infection confirmed in laboratory were fever (n=4,794), cough (n=4,559) and dyspnea (n=4,480). The frequency of these symptoms was similar in patients infected with influenza or with other viruses. Symptoms as sore throat and myalgia were mostly found in patients infected with the influenza virus.

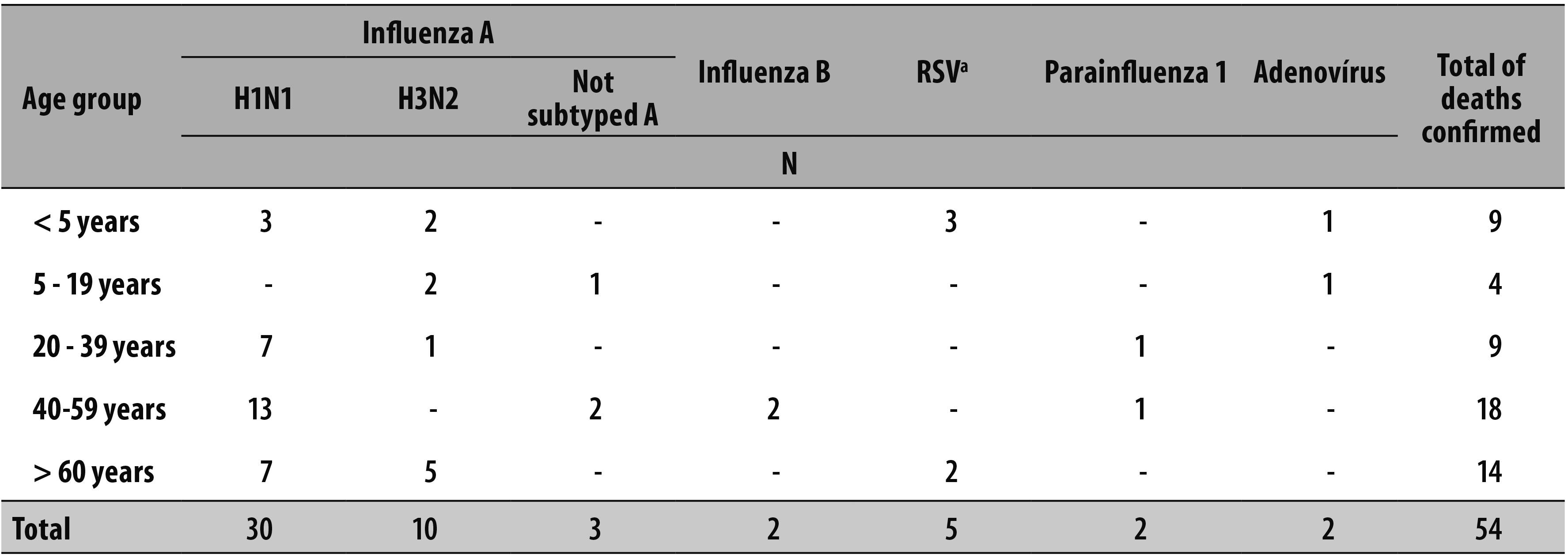

Among the 54 patients infected by respiratory viruses that died, about 80% were infected with the influenza virus, of which 55.6% were infected with the subtype A (H1N1)pdm09, and 43.3% were adults between 40 and 59 years old. Among pregnant and puerperal women reported with severe acute respiratory syndrome, a pregnant woman died because of an infection by subtype (H1N1)pdm09 and a puerperal woman died because of complications from the infection by subtype A(H3N2). Most people aged 60 years old or more that died were infected mostly with influenza viruses subtypes A(H1N1)pdm09 (n=7) and A(H3N2) (n=5). Three children under the age of five died from an infection with A(H1N1) and other 3 children with RSV infection (Table 3).

Discussion

The study results show that intensified surveillance of respiratory virus in Belo Horizonte was of great importance for comprehending the virus circulation in the city and its metropolitan area. Most patients reported with SARS had their samples collected (77.4%) and 17.3% of these samples were positive for virus. This is similar to results found in a study conducted by Freitas, in which the positivity for respiratory viruses was 17.0% of a total of 6,421 positive samples of patients with influenza syndrome - ILI - in the five Brazilian regions from 2000 to 2010.14

Underreporting is likely to have occurred in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, especially in cases discharged from emergency care units (UPA), when the admission to hospitals was unnecessary. The recommendation is that these patients are equally reported and the outcome considered as recovery, since there was no hospitalization.

A great part of health unit professionals contributed to the intensified surveillance of SARS, enabling adequate and timely sample collection. The strategy of including UPA patients awaiting hospitalization was important because of the opportunity of conducting a sample collection and initiating an early antiviral treatment. The focus on the home care service team (HCS), trained at the time of the virus influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic for collecting the samples, strengthened the adequate material collection, preventing samples loss.

It is important to highlight that Belo Horizonte was the first Brazilian city to intensify SARS surveillance to all hospitalized or awaiting hospitalization patients. This study presents the results related to viral monitoring in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte from 2011 to 2013, and the most common cause of illness among the reported patients was the influenza virus infection. The results of this surveillance showed the importance of the epidemiological team in hospitals. The Municipal Health Department encouraged the creation of this service by donating computers to hospitals and expanding the ILI surveillance in the public urgency/emergency care units. The vaccination campaigns in Belo Horizonte lasted longer than the period defined by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, so more people could have access to the immunobiological and to the antiviral drugs (available in all health facilities under the control of the Municipal Health Department). Belo Horizonte also has an Influenza Contingency Plan, with three different hypotheses - routine, alert, epidemic - for monitoring the respiratory virus circulation.

Within this context, the fact that recent population based studies on this subject are scarce in Brazil is noteworthy. Around 20 years ago, a four-year cross-sectional population based study was conducted in the city of Rio de Janeiro focusing on children under five years old.17

In the present study, it was possible to see that influenza was active in all seasons of the year in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte with higher incidences in May and peaks in June and July. The virus seasonality and its occurrence in hospitalized patients in the city were evident in all age groups.

Different age groups suffered from both influenza A virus subtypes. The A(H3N2) subtype infected mostly the extreme ages; and half of those who got influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 were individuals aged 20 to 59 years old, with a higher proportion of adults from 40 to 59 years old. A study conducted in the city of São Paulo with students under 12 years old confirmed such findings among children aged between 5 and 12, of whom most infections corresponded to the subtype A(H1N1)pdm09.18

The RSV was the second virus with highest number of positive samples in this study and the most frequent among children. This virus circulated all over the year with higher incidence from March to May and peak in April. This is a worldwide circulation virus and is responsible for causing annual outbreaks, affecting mainly young children.7,18 These results corroborate with a national level study on ILI samples, with data from 2000 to 2010.14 Another study conducted in the state of São Paulo between 2005 and 2006 showed a higher incidence of RSV in March (37.0%) and July (50.0%), circulating up to August.18 Another study carried out in the same state showed outbreaks of RSV later in the end of autumn and in the beginning of winter with peak in May. At the same time that those findings on periods of higher incidence and circulation of RSV corroborate with the results presented about the RMBH - higher activity in March and April extending until August -, it also reinsure Brazil as a country of continental characteristics and scale. This implies in local conditions and a number of climate variations, equally capable of determining the seasonality of these events.

Still regarding the RSV, the analysis of ages of infected individuals shows that the highest number of positive cases stroke children under the age of five which is also similar to findings in the international literature.19,20 There are three systematic reviews of literature showing a reduction on hospitalizations in high risk infants after the introduction of a monoclonal antibody against RSV: the palivizumab.

However, before taking any measures it is necessary to understand the virus seasonality.21-23 Results reported in revisions are similar and show how the prophylaxis with palivizumab was efficient in reducing hospitalization number and hospitalization in ICU: among preterm newborns (35 weeks of life) or children with a chronic lung disease there was a reduction of 55.0% in the hospitalization rate; and among children with congenital heart disease this reduction was of 45.0%. On the other hand, the results for the reduction of mortality are controversial.

More than half of reported deaths occurred to people aged 60 years old or more (51.9%). However, adults between 20 and 59 years old corresponded to half of the number of deaths positive for respiratory virus, especially the influenza virus A(H1N1)pdm09, with 72.2% of deaths among adults in this age group. In France and in the United States, the mortality rate of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 reached its peak in individuals under 20 years old demonstrating the susceptibility of these individuals to the new virus which last circulated in 1957 and also confirmed the low age as an important mortality risk factor for this infection.24 It is important to highlight that an explanation hypothesis for the largest number of infect people being adults is the fact that the immunization against influenza does not reach this public or most part of it, and the fact that the elderly are included in Brazilian vaccination campaigns since its beginning in 1990s.

People aged 60 years or more were the second group with the largest number of positive deaths, and half of them were infected by the virus A(H1N1)pdm09. In the world, influenza is the sixth leading cause of death, especially among the elderly with chronic diseases.25 Future studies are welcome in the sense of better evaluating the importance of preventing this disease through vaccination of vulnerable groups, such as the elderly,26 and the expansion of vaccination campaigns for other groups. Equally important is to evaluate the factors that predispose the increase in morbidity and mortality due to a respiratory disease, offering more subsidies for adapting health policies in this area.

The techniques used have different sensibilities and specialties. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) provides sensitivity around 70.0% and 80.0%. The reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is more sensitivity (80.0%) and specific (95.0%). Although the number of positive samples is considerably low (17.3%), this study allowed us to understand the morbidity and mortality profile of hospitalized patients in Belo Horizonte with acute respiratory condition, the most prevalent viruses and the respective age groups during the observed period.

However, it is necessary to consider possible limitations to achieve the study goals when interpreting and discussing results. The information system used was restricted to Belo Horizonte and is mostly based on passive report, which does not reflect effectively all hospitalizations due to respiratory diseases in the city or possible SARS cases that had not been reported. Furthermore, the study was based on secondary data. The lack of some information, such as vaccination status (with viral identification in people previously vaccinated), ethnicity/skin color, education level, disease period and initial date of antiviral use hampered the analysis of these variables and its possible correlation with the disease. Influenza A samples without identification of the subtypes were identified as "A not subtyped", which accounted for about 4% of the cases. Even if those samples did not belong to the subtype A (H1N1)pdm09, we could affirm that they did not belong to the subtype A(H3N2). In addition, it was not possible to calculate the mortality and lethality rates. Not only because sometimes it was impossible to prove that all patients with SARS had been hospitalized in Belo Horizonte, but also because among the hospitalized individuals, not all of them had been reported on the system. Finally, there are few studies published in Brazil dedicated to respiratory virus surveillance14 and they are usually restrict to surveillance in specific hospitals.6,7 Other studies are related to influenza vaccination coverage or to techniques used to identify the circulating respiratory viruses.27

Despite these limitations, it is possible to affirm that the presented analysis contributes to a greater magnitude, distribution and seasonality knowledge on respiratory viruses in the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte.

It can be concluded that the proposed respiratory virus surveillance in Belo Horizonte allowed us to understand the profile of morbidity and mortality of hospitalized patients with acute respiratory condition, the predominant viruses and the corresponding age group. It is possible to improve the service response by implementing and/or improving the hospitals with epidemiological surveillance (NUVEH) that are prepared for the early detection of changes in virus circulation pattern, especially influenza virus which is mutable and capable of causing epidemics and pandemics. Extended vaccination campaigns, recommending the early antiviral therapy and different care to risk groups can be efficient strategies in reducing the mortality of these groups.

Although the present study contemplates a heavily populated metropolitan area in the state of Minas Gerais, it is still necessary to conduct other researches with samples from different parts of the country and different age groups, allowing the comparison of results of seasonality of respiratory viruses, most susceptible age groups to infections, risk factors and lethality and mortality rates. Further studies may contribute to formulating more appropriate public policies in order to reduce the occurrence of acute respiratory diseases, and the number of hospitalization and deaths due to these causes.

Referências

1. Durigon EL. Diagnóstico viral: o que acrescentam os novos métodos? In: Kfouri RA, Berezin EN, Almeida F. Atualização em vírus respiratórios: 2012. São Paulo: Segmento Farma editores; 2013. p.29-34. [ Links ]

2. Berezin EN. Vírus respiratórios: quais são os principais fatores de risco? In: Kfouri RA, Berezin EN, Almeida F. Atualização em vírus respiratórios: 2012. São Paulo: Segmento Farma editores; 2013. p.47-54. [ Links ]

3. Ruuskanen O, Lahti E, Jennings LC, Murdoch DR. Viral pneumonia. Lancet. 2011 Apr;377(9773):1264-75. [ Links ]

4. Pitrez PMC, Stein RT, Stuermer L, Macedo IS, Schmitt VM, Jones MH, et al. Bronquiolite aguda por rinovírus em lactentes jovens. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2005 set-out;81(5):417-20. [ Links ]

5. Alvarez AE, Marson FAL, Bertuzzo CS, Arns CW, Ribeiro JD. Epidemiological and genetic characteristics associated with the severity of acute viral bronchiolitis by respiratory syncytial virus. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013 Nov-Dec;89(6):531-43. [ Links ]

6. Costa LF, Yokosawa J, Mantese OC, Oliveira TFM, Silveira HL, Nepomuceno LL, et al. Respiratory viruses in children younger than five years old with acute respiratory disease from 2001 to 2004 in Uberlândia, MG, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006 May;101(3): 301-6. [ Links ]

7. Thomazelli LM, Vieira S, Leal AL, Sousa TS, Oliveira DBL, Golono MA, et al. Vigilância de oito vírus respiratórios em amostras clínicas de pacientes pediátricos no sudeste do Brasil. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2007 set-out;83(5):422-8. [ Links ]

8. Olmos RD. Vírus respiratórios e pneumonias bacterianas em adultos. In: Kfouri RA, Berezin EN, Almeida F. Atualização em vírus respiratórios: 2012. São Paulo: Segmento Farma editores; 2013. p.107-12. [ Links ]

9. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. O desafio da influenza: epidemiologia e organização da vigilância no Brasil. Bol Epidemiol. 2004;4(1):1-7. [ Links ]

10. Bonvehí PE, Istúriz ER, Labarca JA, Rüttimann RW, Vidal EI, Vilar-Compte D. Influenza among adults in Latin America, current status, and future directions: a consensus statement. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2012 Jun;31(6):506-12. [ Links ]

11. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Surto de influenza no extremo oeste de Santa Catarina, setembro de 2002. Bol Epidemiol. 2002; 2(4):1-7 [ Links ]

12. Schuelter-Trevisol F, Dutra MC, Uliano EJM, Zandomênico J, Trevisol DJ. Perfil epidemiológico dos casos de gripe A na região sul de Santa Catarina, Brasil, na epidemia de 2009. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2012 Jul;32(1):82-6. [ Links ]

13. Vieira SE, Gilio AE, Durigon EL, Ejzenberg B. Lower respiratory tract infection caused by respiratory syncytial virus in infants: the role played by specific antibodies. Clinics (São Paulo). 2007 Dec;62(6):709-16. [ Links ]

14. Freitas FT. Sentinel surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses, Brazil, 2000-2010. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013 Jan-Feb;17(1):62-8. [ Links ]

15. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Banco de dados agregados [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2010 [citado em 2014 jul 07 ]. Disponível em: http://www.sidra.ibge.gov.br/bda/popul/default.asp?t=3&z=t&o=22&u1=1&u2=1&u4=1&u5=1&u6=1&u3=34 [ Links ]

16. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Protocolo de tratamento de influenza: 2013 [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2013 [citado em 2014 ago 18]. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/protocolo_tratamento_influenza.pdf [ Links ]

17. Nascimento JP, Siqueira MM, Sutmoller F, Krawczuk MM, Farias V, Ferreira V, et al. Longitudinal study of acute respiratory diseases in Rio de Janeiro: occurrence of respiratory viruses during four consecutive years. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1991 Jul-Ago; 33(4):287-96. [ Links ]

18. Guatura SB, Watanabe ASA, Camargo CN, Passos AM, Parmezan SN, Tomazella TKC, et al. Surveillance of influenza A H1N1 2009 among school children during 2009 and 2010 in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012 Sep-Oct;45(5): 563-6. [ Links ]

19. Iwane MK, Farnon EC, Gerber SI. Importance of global surveillance for respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 2013 Dec;208 Suppl 3:S165-6. [ Links ]

20. Piñeros JG, Baquero H, Bastidas J, García J, Ovalle O, Patiño CM, et al. Infecção por vírus sincicial respiratório como causa de internação na população com menos de 1 ano na Colômbia. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013 nov-dez;89(6):544-8. [ Links ]

21. Checchia PA, Nalysnyk L, Fernandes AW, Mahadevia PJ, Xu Y, Fahrbach K, et al. Mortality and morbidity among infants at high risk receiving prophylaxis with palivizumab: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011 Sep;12(5):580-8. [ Links ]

22. Morris SK, Dzolganovski B, Beyene J, Sung L. A metaanalysis of the effect of antibody therapy for the prevention of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2009 Jul; 9:106. [ Links ]

23. Wang D, Bayliss S, Meads C. Palivizumab for immunoprophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis in high-risk infants and young children: a systematic review and additional economic modelling of subgroup analyses. Health Technol Assess. 2011 Jan;15(5):iii-iv. [ Links ]

24. Lemaitre M, Carrat F. Comparative age distribution of influenza morbidity and mortality during seasonal influenza epidemics and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2010 Jun;10:162. [ Links ]

25. Gomes AA, Nunes MAP, Oliveira CCC, Lima SO. Doenças respiratórias por influenza e causas associadas em idosos de um município do nordeste brasileiro. Cad Saude Publica. 2013 jan; 29(1):117-22. [ Links ]

26. Bós AJG, Mirandola AR. Cobertura vacinal está relacionada à menor mortalidade por doenças respiratórias. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2013 maio;18(5):1459-62. [ Links ]

27. Cavalcante RS, Jorge AMZ, Fortaleza CMCB. Predictors of adherence to influenza vaccination for healthcare workers from a teaching hospital: a study in the prepandemic era. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010 nov-dec; 43(6):611-4. [ Links ]

Received: May 18, 2015; Accepted: December 19, 2015

texto em

texto em