Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2337-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde v.25 n.2 Brasília abr./jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742016000200007

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Skin-to-skin contact at birth: a challenge for promoting breastfeeding in a "Baby Friendly" public maternity hospital in Northeast Brazil*

1Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Unidade Materno-Infantil do Hospital Universitário Lauro Wanderley, João Pessoa-PB, Brasil

2Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Saúde Pública, São Paulo-SP, Brasil

3Universidade Católica de Santos, Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva, Santos-SP, Brasil

OBJECTIVE:

to identify prevalence of compliance with the fourth step of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative - to put the babies in skin-to-skin contact with their mothers immediately after birth for at least half an hour - in a public hospital in Northeast Brazil.

METHODS:

this was a cross-sectional study using data from interviews with mothers who had recently given birth during a typical week in 2014.

RESULTS:

107 mothers were interviewed; 9.3% had completed the fourth step properly; the fourth step was negatively associated to cesarean section (p<0.01), and adequacy was not associated with receiving guidance on breastfeeding during the prenatal period or with breastfeeding in the first hour of life.

CONCLUSION:

low compliance with the fourth step is cause for concern, especially because this is a Baby-Friendly Hospital; cesarean section was detrimental to infant skin-to-skin contact with their mothers immediately after birth.

Keywords: Breastfeeding; Maternal and Child Health; Public Health; Cross-Sectional Studies

Introduction

The fourth of ten steps for successful breastfeeding - recommended by the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) - is to put babies in skin-to-skin contact with their mothers immediately after birth for at least an hour, encouraging mothers to recognize when their babies are ready to be breastfed. This is an essential practice for the promotion and encouragement of breastfeeding.1

Established in 1990, BFHI is supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Since then, over 15,000 hospitals in 134 different countries received a Baby-Friendly Hospital title, contributing to improve the rates on breastfeeding and children's health.2

To meet BFHI recommendations regarding the encouragement of breastfeeding, the Stork Network (Rede Cegonha) recommends the adoption of best practices during labour and birth, one of which is the fourth step of BFHI. Stork Network's main objective is to ensure children the right to have a safe birth, a healthy growth and development.3

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in an attempt to improve the prevalence of breastfeeding in the United States of America (USA), introduced, in 2013, two new quality indicators to monitor the breastfeeding policy: (i) percentage of mother-baby binomials put in skin-to-skin contact in the first hour of life; and (ii) the percentage of mothers and babies who stayed on shared accommodation throughout their stay in maternity.4

The impact of putting BFHI into practice positively influenced the duration and early initiation of breastfeeding, and also the exclusive breastfeeding. That has been demonstrated through several researches carried out in different countries and cultural backgrounds.5-7

A study using secondary data on the proportion of children breastfed in their first hour of life and the neonatal mortality rate in 67 countries shows that countries with the lowest breastfeeding tertiles in the first hour of life had higher neonatal mortality rate. This difference remained even after adjustments between deliveries occurred in medical facilities and the mother's education level.7

In order to build favourable evidence to the fourth step of the BFHI, a meta-analysis showed that the early skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby has a positive effect on breastfeeding between the first and the fourth months after birth, on the glucose levels during the newborns first hours of life and on the cardiorespiratory stability of late preterm infants.8

Early skin-to-skin contact between the mother and the baby is a safe and inexpensive procedure that has proven benefits on the short and long term, for mothers and children,9 justifying its systematic implementation at Baby-Friendly Hospitals (BFH).

Despite strong favourable evidences, the fourth step of the BFHI is still unknown and overlooked by many health professionals.10

An evaluation conducted in 2002 on countries' experiences with the implementation of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding showed that the initiatives are easily understood and accepted; however, its sustainability seems to be more effective when it is associated to an approach that includes public policies, legislation, health system reform and contributions for the community.11 In Brazil, the sustainability of BFHI was also evaluated in 2002, when 90% of the accredited hospitals at the time were analysed. Results have shown that 92% of them met all ten steps, and the fourth step was accomplished in 96% of the evaluated hospitals.12

In this context, the aim of this paper was to identify the prevalence of newborns put in skin-to-skin contact with their mothers immediately after birth for at least 30 minutes or until the baby's first breastfeeding. The study was conducted in a public maternity hospital which holds the title of a BFH, located in the Northeast region of Brazil.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional observational study carried out in a public maternity hospital in the city of João Pessoa, the capital of Paraíba State, in the Northeast region of Brazil. This hospital was chosen because its maternity facility has the highest monthly number of live births in Paraíba State: about 670 births a month, approximately 70% of João Pessoa's births and 14% of the births in Paraíba.1 The evaluated maternity hospital holds the title of BFH since 1997.

In order to estimate the prevalence of the fourth BFHI step, face to face interviews were carried out using a structured questionnaire - through the LimeSurveyTM(r) software - applied to women admitted in the hospital's shared accommodation, who had given birth at least 12 and at most 36 hours before the interview. Postnatal women with formal contraindications that hampered skin-to-skin contact with their babies and/or early breastfeeding were excluded, namely: newborns with very low birth weight (less than 1,500g) or with gestational age - evaluated by the Capurro method - below 34 weeks or with Apgar score - at five minutes - below 7; mothers who were positive to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or with positive HIV serology recorded on medical records; and mothers or newborns whose immediate destination was to an intensive care unit (ICU).13 Cases of early neonatal death and/or maternal death were also excluded.

The proper compliance with the fourth step of BFHI (yes, no), putting newborns in skin-to-skin contact with their mother in the first half hour of their lives, as they remained in contact for at least 30 minutes or until the babies' first fed, was considered to be the outcome variable.

The following variables were included to characterize the mothers: age (in years: ≤19; 20 to 29; ≥30); self-reported skin color (white, black, yellow, brown; indigenous); marital status (single, married, unmarried unions, widowed); religion (no religion, catholic, evangelical/protestant, Jehovah's witnesses, other); socioeconomic status, calculated by the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria (CCEB) in social strata (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2, D and E),14 and city of origin (João Pessoa; metropolitan region of João Pessoa; other cities from the state of Paraíba).

Other variables included were: type of labour (vaginal, caesarean section); location where the prenatal care was provided (Primary Health Care Unit [pregnant women at normal conditions]; Reference Center [pregnant women with obstetric risk factors]; Private Clinics); guidance during prenatal care on the importance of breastfeeding (yes, no); and guidance during prenatal care on breastfeeding the baby in their first hour of life (yes, no).

The data were collected in January 2014, for seven days in a row, in a typical week, i.e. no unusual events affected the service, such as holidays, lack of staff or overcrowding, among others, typifying an easily accessed non-probability sample. The interviews began on a Monday and ended on a Sunday. As the institution's work timetable is organized in shifts, with each team working on their specific day, this way of collecting data allowed us to contemplate the various dynamics and routines that could exist at the work environment.

The variables were described by absolute and relative frequencies. The hypothesis test used was Fisher's exact test. The significance level was 5%.

In order to analyse the association between the place where the prenatal care was provided and the type of assistance offered to the interviewed women, the variables adopted were 'type of labour', guidance during the prenatal care on the importance of breastfeeding' and 'guidance during the prenatal care on breastfeeding the baby during the first hour of life'.

With regard to the assessment on whether there was an association of any health care variable with the outcome variable, the frequency of mothers who completed the fourth step of the BFHI properly was compared with the type of labour, place where the prenatal care was provided and the guidance received during the prenatal care on breastfeeding in general and breastfeeding during the first hour of the baby's life.

The softwares Excel and SPSS 20(r) were used.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Lauro Wanderley, from the Federal University of Paraíba: Report No. 508,904 (Brazil Platform).

Results

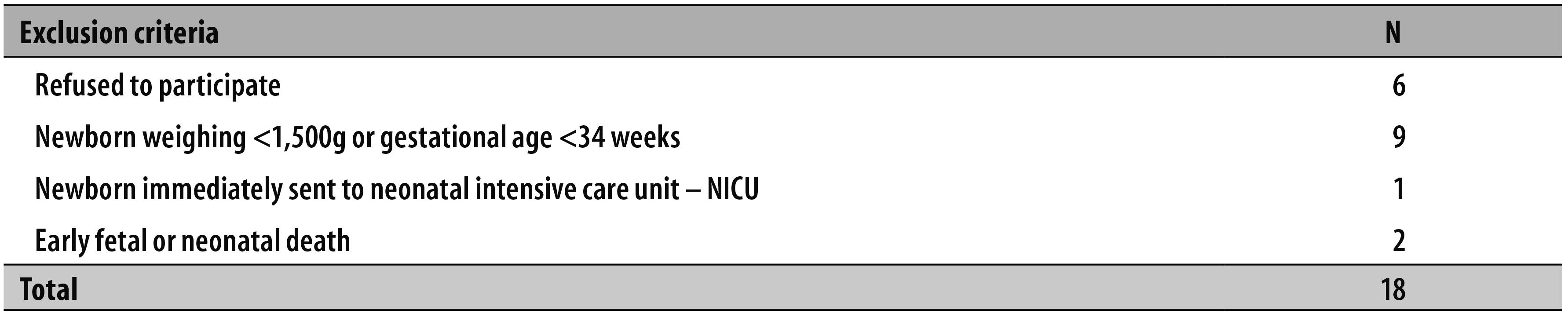

In the week chosen for data collection, in January 2014, a total of 125 women gave birth in the maternity hospital chosen, and 113 of them were eligible for the study. Out of the 113 women, 6 of them refused to participate, resulting in a loss of 5.3% (Table 1). Therefore, 107 patients were interviewed.

Table 1 - Distribution of mothers excluded from the study (n=18), according to the established criteria in a public maternity hospital from João Pessoa , Paraíba State, January 2014

Note: There was no exclusion of mothers with newborns with Apgar score <7 at five minutes, mothers with positive anti-HIV serology, those sent straight to an intensive care unit (ICU) and maternal death.

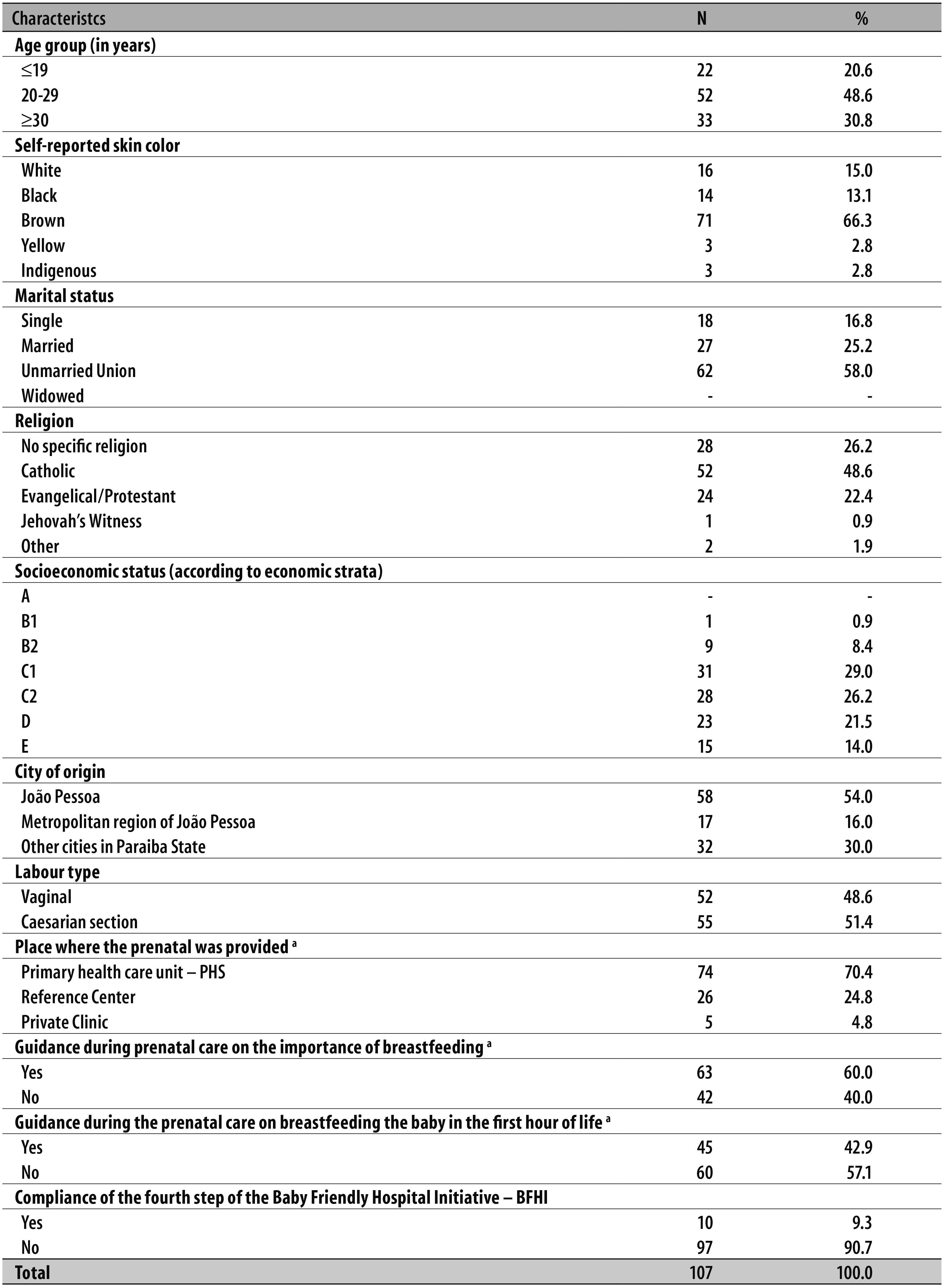

Most of mothers were between 20 and 29 years old (48.6%). The majority self-reported to have brown skin color (66.3%), were in an unmarried union (58.0%) and believed in a particular religion (73.8%). Less than 10% of the interviewees were part of the upper socioeconomic strata. A great part of the patients did not live in the city of João Pessoa (45.8%) (Table 2).

Table 2 - Frequency of mothers (n=107) according to age, self-reported skin color, marital status, religion, socioeconomic status, city of origin, type of labour, place where the prenatal was provided, guidance on breastfeeding during prenatal and compliance with the fourth step of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in a public maternity hospital from João Pessoa, Paraíba State, January 2014

a) Only patients who attended to prenatal care were included.

Only two patients did not get prenatal care. The percentage of caesarean sections was high (51.4%). Most patients got prenatal care in Primary Health Care Units (70.4%) and received guidance on breastfeeding during prenatal care (60.0%); however, most of these guidelines did not include the recommendation of breastfeeding in the first hour of the baby's life (57.1%) (Table 2).

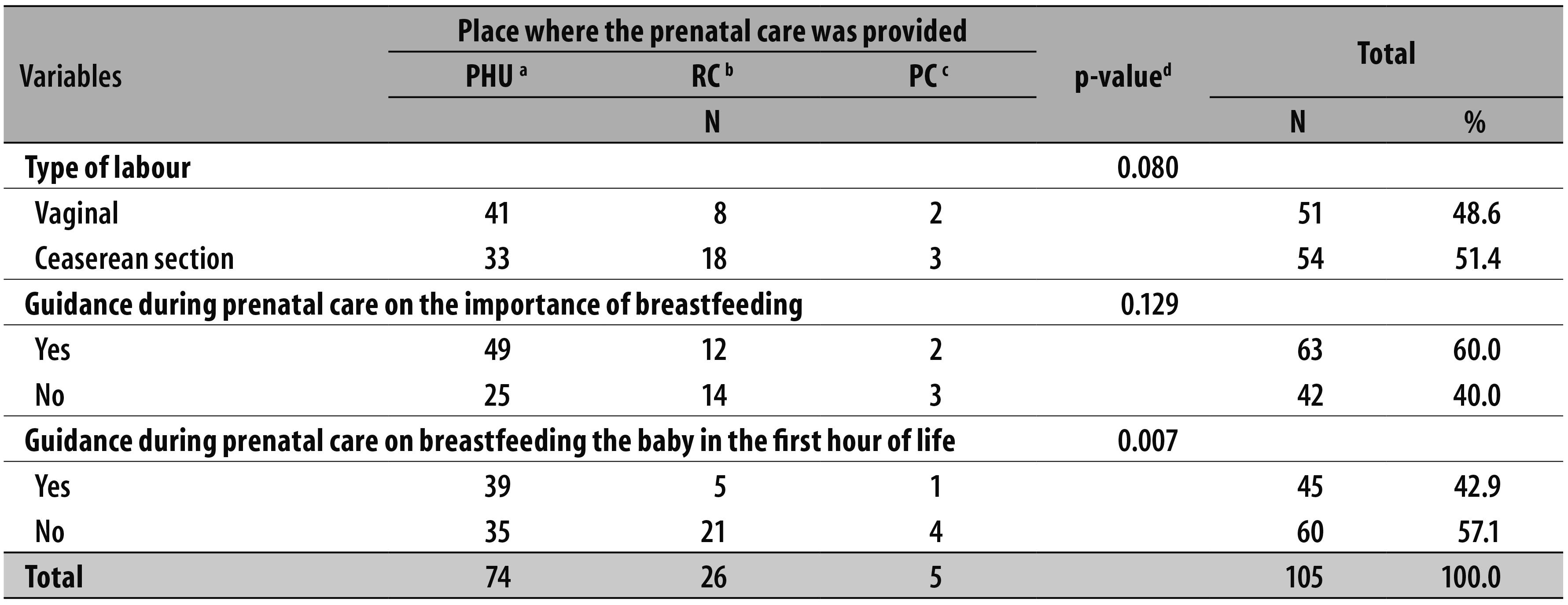

There was no association between where the prenatal care was provided and the type of labour (p=0.08) (Table 3). The percentage of caesarean sections was high among patients who got their prenatal care in Primary Health Care Units (44.6%) (Table 3).

Table 3 - Distribution of the place where mothers got their prenatal care (n=105), in relation to the type of labour and general guidelines received on everyday breastfeeding and in the first hour of the baby's life, in a public maternity hospital from João Pessoa, Paraíba State, January 2014

a) Primary Health Care Unit

b) Reference Center

c) Private Clinic

d) Fisher's exact test

We observed a statistically significant association between getting the prenatal care at a Primary Health Care Unit (PHU ) and receiving guidance on breastfeeding their babies in the first hour of life (p=0.007) (Table 3). Among the mothers who received this guidance, 86.7% got the prenatal care in Primary Health Care Units.

With regard to accomplishing the fourth step of the BFHI, 54 women reported they had received their babies on their lap in the first 30 minutes after birth. The nursing staff, along with pediatricians, was responsible for providing this early contact between the mother and the baby (Table 4).

Table 4 - Absolute number of babies put to early skin-to-skin contact with their mothers, according to the professional responsible for this contact (n=54), in a municipal maternity hospital from João Pessoa, Paraíba State, January 2014

There was no registry of assistance of doulas, physiotherapists, psychologists, or nursing technicians.

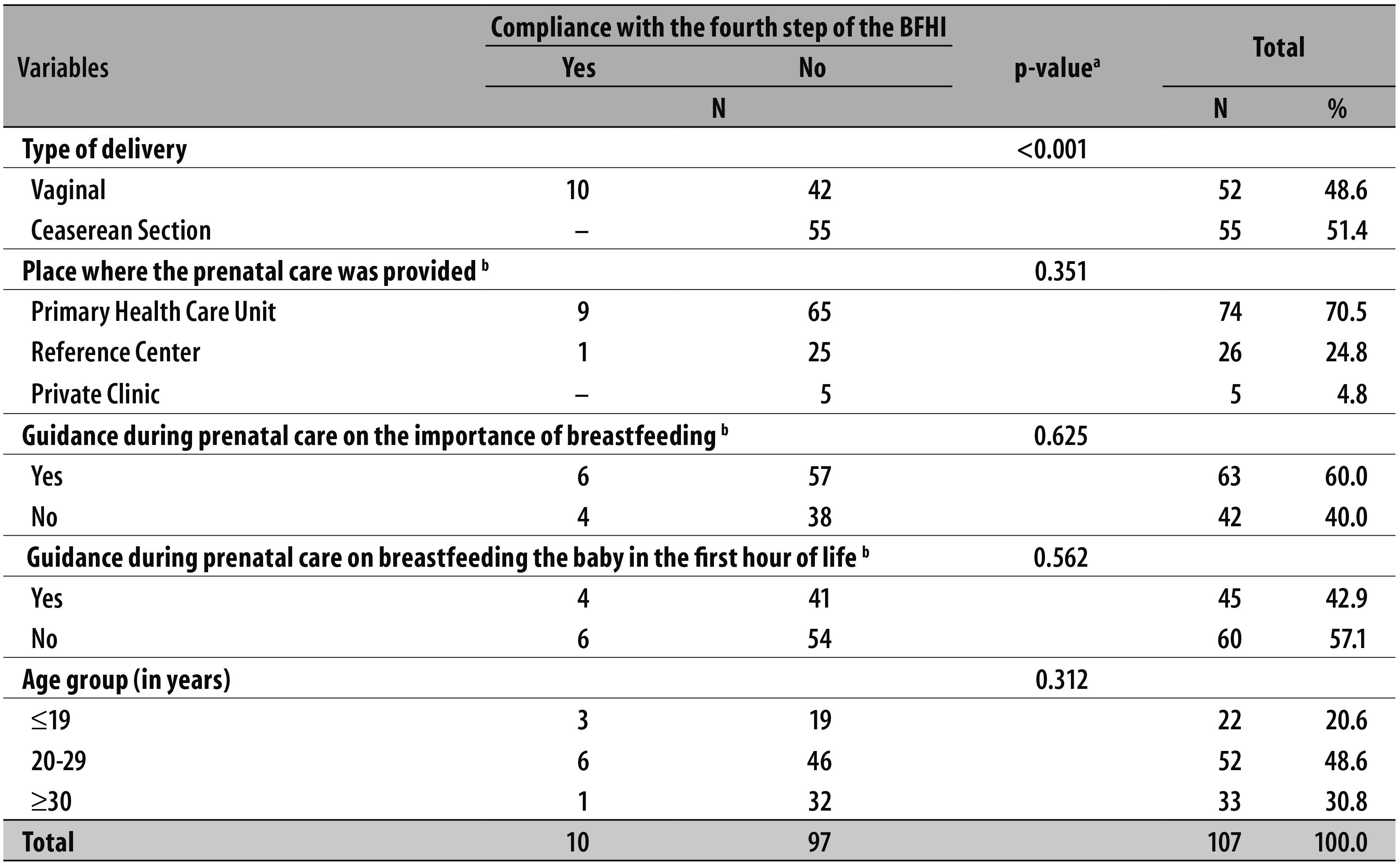

Although many mothers had had the chance to hold their babies in their arms immediately after birth, only 9.3% could have a skin-to-skin contact with their babies for more than 30 minutes or until they had their first breastfeeding - compliance of the fourth step of the BFHI. The labour type was the only significant variable associated with the achievement of the fourth step of the BFHI (p<0.01). No patient who underwent caesarean section had the opportunity to take the fourth step of the BFHI as recommended (Table 5).

Table 5 - Frequency of mothers who completed the fourth step from the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) properly in relation to the labour type, where the prenatal care was provided and guidance on breastfeeding during prenatal care, in a public maternity hospital from João Pessoa, Paraíba State, January 2014

a) Fisher's exact test

b) Only patients who got their prenatal care were included

Discussion

The prevalence of compliance with the fourth step of the BFHI was below the target recommended by the Ministry of Health for the BFH. According to instructions from the Ministry, at least 80% of randomly selected mothers who gave birth without general anaesthesia should confirm that their babies performed the fourth step and that they were encouraged to looking for - during this first contact - signals that their babies were ready to be breastfeed and receive help if necessary.1

All cases that presented any kind of formal contraindications that could hamper skin-to-skin contact with their babies and/or early breastfeeding were excluded. Therefore, the study sample was only composed by babies and mothers who were able to have skin-to-skin contact, as recommended by the Ministry of Health. The finding of this study is alarming, especially because it was conducted in a BFH. However, it is similar to the findings in other hospitals which are not "Child friendly", according to an evaluation carried out by Boccolini et al.15 in Rio de Janeiro between 1999 and 2001. That study showed that only 16.1% of newborns are breastfed in their first hour of life. The Brazilian National Survey on Labour and Birth, conducted between 2011 and 2012, showed similar results.16 In that survey, about 28% of the babies - 28.8% from the Northeast region - had skin-to-skin contact with their mothers shortly after birth, and the proportion of breastfeeding in the delivery room was even lower - 16.1% in Brazil and only 11.5% in the Northeast region.16

The aforementioned findings15,16 reveal that over the past few years, despite growing evidence of an increasing number of hospitals holding the title of "Baby friendly" and the public policies designed to encourage breastfeeding in Brazil, there was no change in the scenario regarding early breastfeeding, revealing a huge discrepancy between the most up to date scientific evidence and the everyday clinical practice of maternity hospitals.

Adherence to the fourth step of the BFHI still remains a challenge throughout the country; even though it is higher in the Northeast region, where the BFHI is established, only a few babies have the chance to be breastfed in their first hour of life.

However, some Brazilian cities managed to improve breastfeeding indicators. This is the case of Feira de Santana, in Bahia State, where, over a period of eight years, an increase of 16.7% was achieved (52.2% in 2001 to 68.9% in 2009) in the proportion of children breastfed in the first hour of life.17

In this study, we found that the nursing staff and the pediatricians were responsible for making the implementation of the fourth step of the BFHI possible, which may be a consequence of how the responsibilities on a typical maternity hospital routine are organized, meaning that the health professionals are the care protagonists, not leaving much room for companions, doulas, obstetricians, and other health professionals that are essentially responsible for the mother's assistance.

The relationship between the adequate compliance with the fourth step of the BFHI and the type of labour is similar to the one observed in another study conducted in the South region of Brazil and published in 2008, which evaluated the factors associated with breastfeeding start. The authors of that study found that both skin-to-skin contact and the time spent by the babies and their mothers soon after birth are reduced in case of caesarean sections, even if other factors are considered.18

Boccolini et al.15 and Moreira et al.16 also found out that vaginal birth is significantly associated to skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding in the first hour of the baby's life. Boccolini et al.15 also observed that breastfeeding in the first hour of life is determined essentially by the maternity facility where the births take place, however individual factors such as age, parity and mother's education level do not play a significant role. These findings15,16 together with this present study show that the choice of the maternity facility interferes with successful breastfeeding in the studied locations. We can affirm that the compliance with the fourth step is connected with the labour care model, and the prevailing labour care model in Brazil is one of the major inducers of the reality observed.

A qualitative research conducted in Australia - a country with a less interventionist labour care model - related to the perception of Australian health professionals regarding the implementation of the BFHI, showed that skin-to-skin contact between the mother and the baby was considered the easier step of the BFHI to be implemented. During the interview, one of the professionals said, "You can just leave your mother and baby there quite happily".19

In the US, where breastfeeding rates are still low, there is an increasing rate of newborns that were put in skin-to-skin contact with their mothers. According to the CDC/USA, maternity hospitals that properly accomplished the fourth step accounted for 90% or more, increasing from 43.4% in 2009 to 54.4% in 2011, thanks to an American national policy that resembles the BFHI worldwide policy.4

A USA study published in 2012 on the difficulties to overcome the barriers that prevented the medical staff of the hospital from adopting the recommended practices by the BFHI points out some issues related to the main problems encountered, such as cultural background, out-dated practices and misinformation. It concluded that overcoming these obstacles requires time and determination. After continuous intervention to change work proceedings related to labour assistance and postpartum, the USA hospital service evaluated managed to expand the practice of the fourth step of the BFHI, from 0% in May 2010 to over 85% December 2010.20

Another point to be questioned in this context is the labour type. As noted in this study, there was a high proportion of non-compliance with the fourth step of the BFHI when the caesarean section was performed.

Leal et al.,21 in the study 'Birth in Brazil' (Nascer no Brasil), conducted between February 2011 and October 2012, found that the caesarean section rate was 51.9% in Brazil. Considering only the usual obstetric caesarean risk, caesarean section rate decreased to 45.5% and natural labour accounted for only 5.6%. Those findings are similar to the ones from the present study: a caesarean section rate of 51.4%.

In both studies, the incidence of caesarean section was high, well above the recommended by the Ministry of Health in its Decree MS/GM No. 2,816 dated 29 May 1998 that established a payment of at most 30% of caesarean sections, compared to the total number of labour per hospital.22

The Brazilian obstetric care model is seen as interventionist. The caesarean section rate is the highest expression of this model and it is among the highest ones in the world,23 close to China (46.2%), Turkey (42.7%), Mexico (42%), Italy (38.4%) and the USA (32.3%); and far superior to England (23.7%), France (20%) and Finland (15.7%).24

Souza and Pileggi-Castro25 observed that the abuse of caesarean sections in Brazil is a complex and varied problem, involving, among other factors, the protagonism of obstetricians on labour care, commercial issues which make this surgery more convenient for many health professionals, and the perception of a considerable portion of the population of the potential superiority of this labour type.

The challenge to change women and newborns health care is huge. It demands strong efforts of many managers and health professionals dedicated to these practices, as well as the participation of women and social movements to share their desires and needs.

The change of this reality should start in family planning and prenatal care, as suggested by the Stork Network (Rede Cegonha), in a timely way, and led by educational and protective actions.3,26

In this study, the coverage of prenatal care for the women interviewed was almost complete, which represents the Brazilian reality.27 More than 60% of the mothers reported having received guidance on breastfeeding during prenatal care, although these advices did not always include breastfeeding in the first hour of the baby's life: less than half of the mothers were instructed to this practice. The results are worse than those found by Viellas et al.27 which presented a ratio of approximately 70.6% of women who gave birth in the Northeast region and 64% of Brazilian mothers who had received guidance on breastfeeding in the first hour of life; the findings of Boccolini et al.,28 were that 25% of the mothers had not received any information about breastfeeding during prenatal care.

Even if in this research the information received on breastfeeding was not associated with the outcome (adequacy of the fourth step), we should question again the women's autonomy and their role within the hospital scenario where they give birth. The understanding of mothers on breastfeeding did not affect the prevalence of the fourth step of the BFHI in the hospital where the study was conducted. This result demonstrates that the hospital routine leads labour care, without incorporating humanitarian precepts, and that mothers are susceptible to the practices within the maternity hospital, having no power to interfere in the decision of having skin-to-skin contact with their babies and/or feed them in their first hour of life.

Association between receiving information on breastfeeding and the place where pregnant women got their prenatal care was not possible, showing that prenatal educational practices are deficient both in Primary Health Care and in Reference Centers.

Boccolini et al.15 reported the need for mothers' empowerment to breastfeed in the delivery room, respecting their condition and sociocultural diversity, so that they can participate as protagonists in the act of breastfeeding their babies in the first hour of life. Monteiro Gomes and Nakano29 understand that the change in attitude of health professionals, with the interaction of the mother-baby binomial, can make the achievement of the fourth step of the BFHI easier, in a way that it will not be a mechanical and fragmented action, but an action conducted with respect and care.

Another aspect to mention is the evaluation process for obtaining and maintaining the title of "Baby-Friendly" Hospital. The evaluators themselves believe that the tools used are partially trustworthy, and are not able to grasp the reality of institutions.30

All in all, the compliance with the fourth step of the BFHI is not conducted as recommended in the hospital where this study was carried out. The low prevalence of skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby in the first hour of life seems to be a reflection of the Brazilian obstetric care model, in which, however, prevails an excess of interventions and female submission.15,21,23,25,29

We suggest new evaluations on BFH, aiming at keeping the quality of care, incorporating the reality and complexity of each maternal and child health unit and its action scenario.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women who participated in this study. All this work would be meaningless without you. It exists only for you, with you and to you. We hope this discussion may contribute to improving care for many other women and babies who are treated daily in all Brazilian maternity hospitals.

REFERENCES

1. Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância. Iniciativa Hospital Amigo da Criança: revista, atualizada e ampliada para o cuidado integrado: módulo 1: histórico e implementação. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2008. (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos). [ Links ]

2. Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância. The Baby-Friendly Hospital initiative [Internet]. New York: UNICEF; 2014 [cited 2016 Mar 07]. Available from: Available from: http://www.unicef.org/programme/breastfeeding/baby.htm [ Links ]

3. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 1.459, de 24 de junho de 2011. Institui no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS - a Rede Cegonha. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília (DF), 2011 jun 27; Seção 1:109. [ Links ]

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding: report card: United States/2013 [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013 [cited 2016 Mar 07]. Available from: Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2013breastfeedingreportcard.pdf [ Links ]

5. Labbok M. Breastfeeding and Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: more important and with more evidence than ever. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2007 Mar; 83(2):99-101. [ Links ]

6. Caldeira AP, Gonçalves E. Assessment of the impact of implementing the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. J Pediatr (Rio J).2007 Mar-Apr;83(2):127-32. [ Links ]

7. Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MI, Pérez-Escamilla R. Breastfeeding during the first hour of life and neonatal mortality. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013 Mar-Apr;89(2):131-6. [ Links ]

8. Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants (review) [Internet]. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2012 [cited 2016 Mar 07]. Available from: Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub3/pdf [ Links ]

9. Mercer JS, Erickson-Owens DA, Graves B, Haley MM. Evidence-based practices for the fetal to newborn transition. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007 May-Jun;52(3):262-72. [ Links ]

10. Toma TS, Rea MF. Benefícios da amamentação para a saúde da mulher e da criança: um ensaio sobre as evidências. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24 supl 2:S235-46 [ Links ]

11. United Nations Children's Fund. 1990-2005: celebrating the innocenti declaration on the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding: past achievements, present challenges and the way forward for infant and young child feeding [Internet]. Florence: UNICEF, 2005 [cited 2016 Mar 8]. Available from: Available from: http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Innocenti_plus15_BreastfeedingReport.pdf [ Links ]

12. Araújo MFM, Otto AFN, Schmitz BAS. Primeira avaliação do cumprimento dos "Dez Passos para o Sucesso do Aleitamento Materno" nos Hospitais Amigos da Criança do Brasil. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2003 out-dez;3(4):411-9. [ Links ]

13. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 371, de 07 de maio de 2014. Institui diretrizes para a organização da atenção integral e humanizada ao recém-nascido (RN) no Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília (DF), 2014 mai 8; Seção 1:50. [ Links ]

14. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa. Critério de classificação econômica: Brasil [Internet]. São Paulo: Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa; 2014[citado 2016 Mar 3]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil [ Links ]

15. Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MIC, Vasconcellos AGG. Fatores associados à amamentação na primeira hora de vida. Rev Saude Publica. 2011 nov;45(1):69-78. [ Links ]

16. Moreira MEL, Gama SGN, Pereira APE, Silva AAM, Lansky S, Pinheiro RS, et al. Práticas de atenção hospitalar ao recém-nascido saudável no Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2014; 30 sup 1:S128-139. [ Links ]

17. Vieira GO, Reis MR, Vieira TO, Oliveira NF, Silva LR, Giugliani ER. Trends in breastfeeding indicators in a city of northeastern Brazil. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015 May-Jun;91(3):270-7. [ Links ]

18. Silveira RB, Albernaz E, Zuccheto LM. Fatores associados ao início da amamentação em uma cidade do sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2008 jan-mar;8(1):35-43. [ Links ]

19. Schmied V, Gribble K, Sheehan A, Taylor C, Dykes FC. Ten steps or climbing a mountain: a study of Australian health professionals' perceptions of implementing the baby friendly health initiative to protect, promote and support breastfeeding. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Aug;11:208 [ Links ]

20. McKeever J, Fleur RS. Overcoming barriers to baby-friendly status: one hospital's experience. J Hum Lact. 2012 Aug;28(3):312-4. [ Links ]

21. Leal MC. et al. Nascer no Brasil: inquérito sobre parto e nascimento: sumário executivo temático da Pesquisa [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2014 [citado 2016 Mar 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.ensp.fiocruz.br/portal-ensp/informe/site/arquivos/anexos/nascerweb.pdf [ Links ]

22. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria n° 2.816, de 29 de maio de 1998. Estabelece critérios para o pagamento do percentual máximo de cesárea, em relação ao total de partos por hospital. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília (DF), 1998 jun 2; Seção 1:48. [ Links ]

23. Barros FC, Victora CG, Barros AJ, Santos IS, Albernaz E, Matijasevich A, et al The challenge of reducing neonatal mortality in middle-income countries: findings from three Brazilian birth cohorts in 1982, 1993, and 2004. Lancet. 2005 Mar; 365(9462):847-54. [ Links ]

24. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators [Internet]. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development;2011[cited 2016 Mar 8]. Available from: Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2011-en [ Links ]

25. Souza JP, Pileggi-Castro C. Sobre o parto e o nascer: a importância da prevenção quaternária. Cad Saude Publica. 2014; 30 supl 1:S11-13. [ Links ]

26. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Pré-natal e puerpério: atenção qualificada e humanizada: manual técnico. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde , 2006. 163 p. (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos); (Série Direitos Sexuais e Direitos Reprodutivos; Caderno nº 5) [ Links ]

27. Viellas EF, Domingues RMSM, Dias MAB, Gama SGN, Theme Filha MM, Costa JV, et al. Assistência pré-natal no Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2014; 30 supl 1:S85-100. [ Links ]

28. Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MIC, Leal MC, Carvalho MS. Fatores que interferem no tempo entre o nascimento e a primeira mamada. Cad Saude Publica. 2008 nov;24(11):2681-94. [ Links ]

29. Monteiro JCS, Gomes FA, Nakano AMS. Percepção das mulheres acerca do contato precoce e da amamentação em sala de parto. Acta Paul Enferm. 2006; 19(4):427-32. [ Links ]

30. Oliveira LS, Espírito Santo ACG. O processo de avaliação da Iniciativa Hospital Amigo da Criança sob o olhar dos avaliadores. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2013 out-dez;13(4):297-307. [ Links ]

* This work was part of the Master's thesis on Public Health entitled 'Strengthening Breastfeeding Practice in Public Maternity Hospitals in the Delivery Room of João Pessoa's Child Friendly Maternity Hospital: an Intervention Study', defended by the main author, Ádila Roberta Rocha Sampaio, at the Catholic University of Santos-SP, in 2015.

Received: November 13, 2015; Accepted: February 20, 2016

texto em

texto em