Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2337-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.26 no.4 Brasília dez. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742017000400013

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Assessment of the implementation of the Leprosy Control Program in Camaragibe, Pernambuco State, Brazil*

1Secretaria Estadual de Saúde de Pernambuco, Diretoria de Vigilância à Saúde, Recife-PE, Brasil

2Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira, Diretoria de Ensino, Recife-PE, Brasil

OBJECTIVE:

to assess the implementation of the actions of the Leprosy Control Program in Camaragibe, Pernambuco State, Brazil.

METHODS:

evaluative research with ‘implementation analysis’, based on criteria, indicators and parameters guided from the construction of the Logic Model; four components were assessed - management, health care, epidemiological surveillance, health education and communication -; direct observation/questionnaire was used, as well as data from the Information System for Notifiable Diseases.

RESULTS:

the implementation of the program was incipient (58.3%); the estimate for the components varied from ‘not implemented’ (health education and communication, 48.0%), ‘incipient’ (management, 53.3%; health care, 57.2%) to ‘partially implemented’ (epidemiological surveillance, 73.0%); in 2012, it was observed low proportion of examined contacts (28.4%), treatment dropout (34.1%), limited standardization of patient care flow, and poor resolution of problems by managers.

CONCLUSION:

the level of implementation found was related to the organization of services, with negative repercussions regarding the result indicators.

Keywords: Health Evaluation; Leprosy; Communicable Disease Control; Program Evaluation; Primary Health Care

Introduction

Leprosy, an ancient infectious disease of chronic evolution, affects mainly the skin and peripheral nerves, leading to deformities and permanent physical disability, related to late diagnosis.1

Currently, the efforts to eliminate leprosy are concentrated in regions of high endemicity, located in some areas of India, Brazil, Indonesia, Congo, Nepal, Tanzania, Philippines, Madagascar, and Mozambique, where the disease is still an important Public Health issue.2 India and Brazil remain, respectively, as the first and second countries on incidence of leprosy.2

In the Americas, Brazil is the country that has most cases of the disease, which remains with high magnitude in the North and Midwest macro-regions and in the metropolitan areas of the Northeast of the country.3

In Pernambuco State, in 2012, the endemicity prevalence was medium (from 4.9 to 1.0/10 thousand inhabitants), the general detection coefficient was very high (from 20.0 to 39.9/100 thousand inhabitants), and, among individuals under 15 years old, it presented hyperendemicity (values over 10.0/100 thousand inhabitants), according to parameters of the World Health Organization (WHO).4

These indicators point to an intense process of transmission and spread of the disease, which presents reported cases in almost every municipality in Pernambuco, with higher concentration in the Metropolitan Region of Recife, such as the municipality of Camaragibe: with a very high general detection rate, ranging from 20.00 to 39.99/100 thousand inhabitants in 2008, this municipality is seen as one of the most endemic of the state.4

The use of multidrug therapy in the treatment of the disease, the strategy to tackle the disease in endemic countries to less than a case per 10 thousand inhabitants and the decentralization of leprosy control actions (LCA) to primary health care, represent progress in the public policies of disease control worldwide. In Brazil, the implementation of LCA by the Family Health Strategy occurred in 1998 and represented an important guideline, adopted by the National Leprosy Control Program, to reduce the occurrence of the disease and break the transmission chain in the population.5

Despite the efforts and achievements, there are obstacles not only technical but also administrative and operational in the development of LCA that interfere in the process of decentralization of these actions. Among them, we should mention the fragility of appropriate assessment tools and systematic analysis of routine services, especially of municipal scope, with great impact on the program effectiveness.6-8 Evaluation studies contribute to the improvement of interventions, and are a management tool that promotes the organization of services and dialogue between practice and management, enabling the institutionalization of assessment practices.9

The objective of the present study was to assess the implementation actions of the Leprosy Control Program in the municipality of Camaragibe, Pernambuco State, Brazil, in 2013.

Methods

Design

Evaluation study, with ‘implementation analysis' of its second component, related to the influence of the implementation degree of the intervention over the observed effects.9 Additionally, a normative assessment was performed in 2013, to compare the criteria and rules of the National Leprosy Control Program to what was observed at the place of the study. The investigation strategy was of single-case study, for enabling the observation of behaviors and organizational processes in many levels,10 with the municipality of Camaragibe being the analysis unit and the Municipal Leprosy Control Program (MLCP), the case.

Context

Camaragibe is located in the west area of the Metropolitan Region of Recife, with total land area of 52.09 km2, demographic density of 2,654 inhabitants/km2 and estimated population, in 2012, of 146,847 inhabitants. The municipality has 29 neighborhoods, grouped into five political-administrative regions.11 The MLCP of Camaragibe is developed at the primary care network, through the Primary Health Care, and is composed of 42 Family Health teams, distributed into 40 Family Health units, besides a team of the Community Health Agents Program (CHAP) and a reference unit. The latter was excluded from the study for not developing actions of the program during the investigation period.

Stages of the evaluation process

The assessment was developed in four steps, as outlined below:

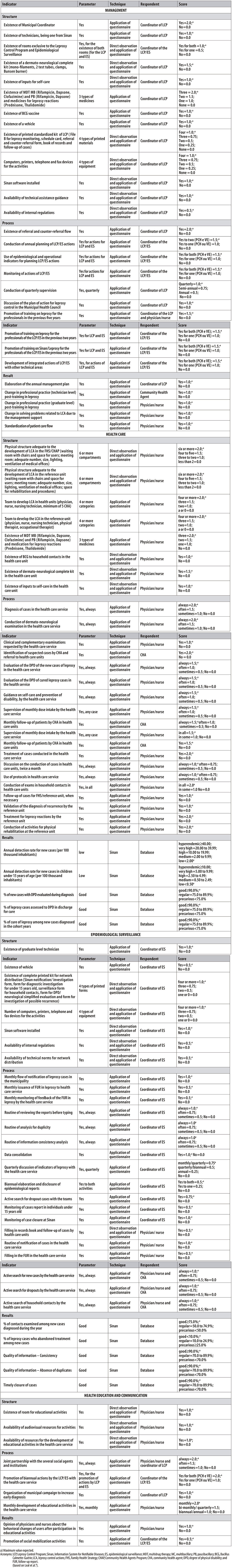

Step 1 - Construction of the Logical Model of MLPC

The Logical Model of MLPC intends to clarify the complex relationship between the structure, the process and the result and allows verifying the difference between planned intervention of LCA and empirical reality. The program was structured according to strategic areas (components) of the National Program: health care; epidemiological surveillance; management; and health education and communication. These strategic areas were developed by the teams from Family Health Care, at the management level of the Municipal Health Department of Camaragibe. The following documents from the Ministry of Health were used for its elaboration: Regulations and Ordinances (Ordinance No. 3,125, dated October 7th, 2010, which approves the guidance for surveillance, health care and control of leprosy; and Ordinance No. 594, dated October 29th, 2010, which classifies the comprehensive care for leprosy into levels I, II and III, in accordance with the infrastructure, competencies, equipment and core team); Technical Guides (Guide to Leprosy Control, 2002; Booklets for Primary Health Care Surveillance - Leprosy, 2.ed., 2008); and Management Report of the General-Coordination of the National Leprosy Control Program, 2011.12 The need to use institutional documents from the Ministry of Health owes to the fact that these municipal programs adopt the guidelines and defined activities, recommended and validated in national scope, and their execution is the responsibility of municipalities. Figure 1 presents the Logical Model of MLPC, listing the activities and results expected to each of the four components aforementioned.

Figure 1 - Summary of the Logical Model of the Leprosy Control Program in Camaragibe, Pernambuco, 2013

Step 2 - Development of the measure and judgment matrix

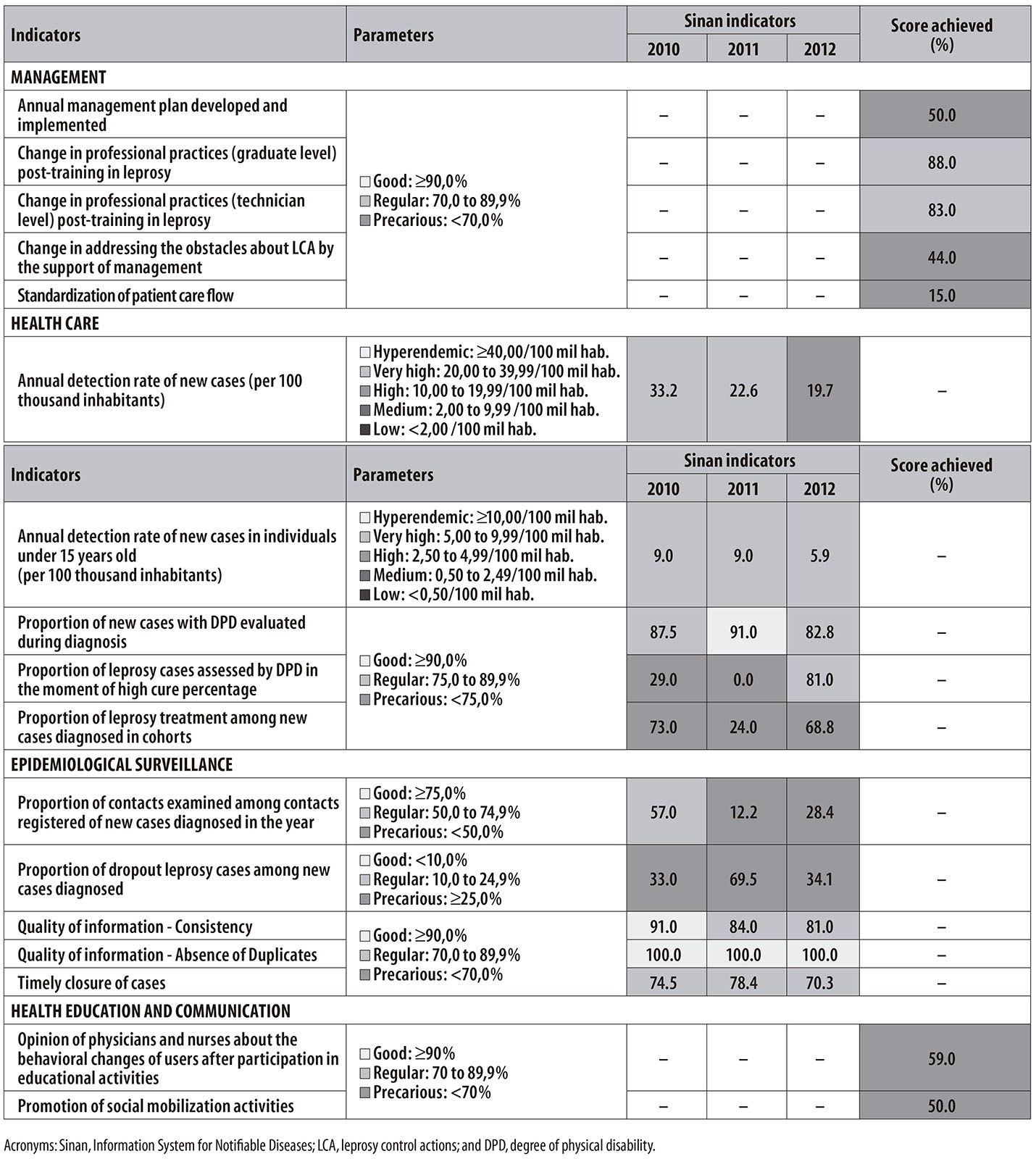

The Logical Model subsidized the development of the assessment questions that composed the measure and judgment matrix. Figure 2 presents, for each of the four components of MLPC, (i) indicators of structure, process and result dimension, (ii) parameters adopted for judgment and (iii) sources of data specified per indicator. The parameters were defined according to institutional documents or found in literature and, in case they were inexistent, referred by the researchers. The valuation of each selected indicator considered its degree of relevance on a scale from zero to 2, based on a previous study.8

Data collection

The indicators listed in the matrix were composed of (i) primary data, through non-participant direct observation, based on a script, and (ii) application of a questionnaire to professionals responsible for the program coordination (1), epidemiological surveillance (1) and health care - physicians, nurses and community health agents (CHA) (78), totalizing 80 professionals surveyed. The professionals with less than six months of work in the Family Health team and those working in units with no report of cases were excluded from the study. The data collection was performed from July to September 2013. The secondary data were extracted from the database of the Information System for Notifiable Diseases (Sinan) in leprosy, in August 2013.

Step 3 - Classification of degree of implementation

To calculate the degree of implementation, data from the normative assessment on structure and process indicators of each component were used. To calculate the degree of implementation of MLPC, maximum expected scores were referred to each of the components, taking into consideration their relevance in the reconstruction of the object study: management (30); health care (40); epidemiological surveillance (20); and health education and communication (10).

Initially, we determined the values observed (S of indicators scores) and calculated the degree of implementation, in percentage (S observed/S of maximum expected value x 100), for each component. The total degree of implementation was based on the sum of the listed indicators. The value obtained was compared with the maximum expected value of each component, obtaining the proportion to be classified as follows: program ‘implemented' (90.0 to 100.0%), ‘partially implemented' (70.0 to 89.9%), ‘incipient' (50.0 to 69.9%) and ‘not implemented' (<50.0%). The ranking, rated by us, had higher level of demand than the traditionally used, due to the strictness of the epidemiological indicators and period of continuous activity of the program evaluated.

Step 4 - Analysis of results (effects) and influence of degree of implementation on the observed effects

The analysis of effects was performed taking into consideration the indicators contained in the matrix of measures of the Leprosy Control Program for the period 2010-2012, last years with information available on Sinan database. All indicators are represented in Figure 2, including the result, and the respective framework for judgment. After the definition of the degree of implementation of each component and the set of MLPC, these degrees were compared to the result indicators, confronting them with the developed model, overlapping each other to identify the aspects that strengthened or undermined the achievement of results.

Results

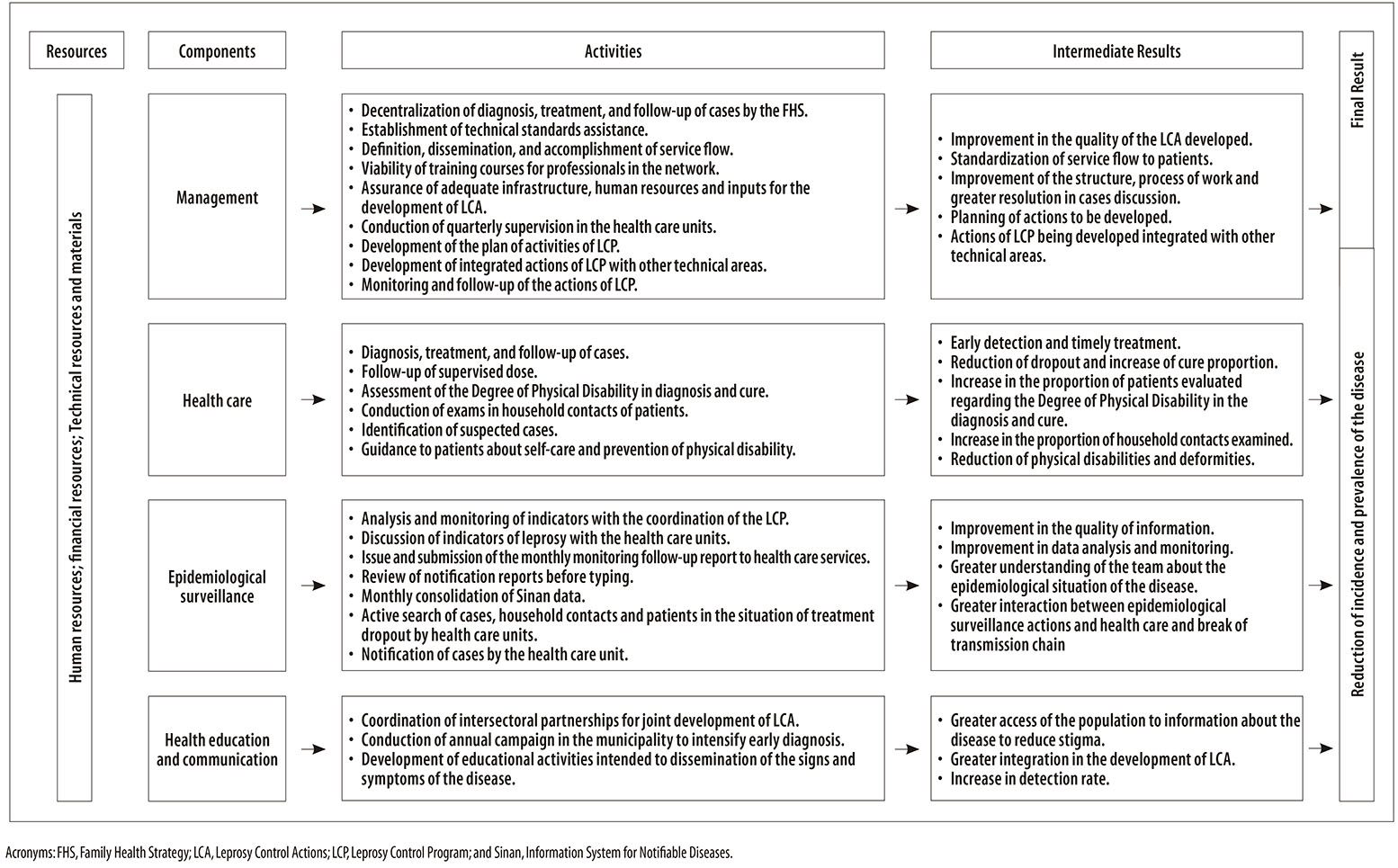

Figure 3 details the set of indicators of structure and process used to assess the degree of implementation of the Municipal Leprosy Control Program of Camaragibe, the maximum values expected and reached for each component of MLPC, based on the definition of the degree of implementation of the intervention.

Figure 3 - Score of indicators used in the assessment of the degree of implementation of the Leprosy Control Program, according to the Logical Model component, in Camaragibe, Pernambuco, 2013

Figure 4 shows a summary of expected and reached values for each component and level of implementation of MLPC. The total level of implementation of MLPC of Camaragibe was classified as ‘incipient' (58.3%). The degree of implementation by component ranged from ‘not implemented' (health education and communication, 48.0%) to ‘incipient' (management, 53.3%; health assistance, 57.2%) and ‘partially implemented' (epidemiological surveillance, 73.0%).

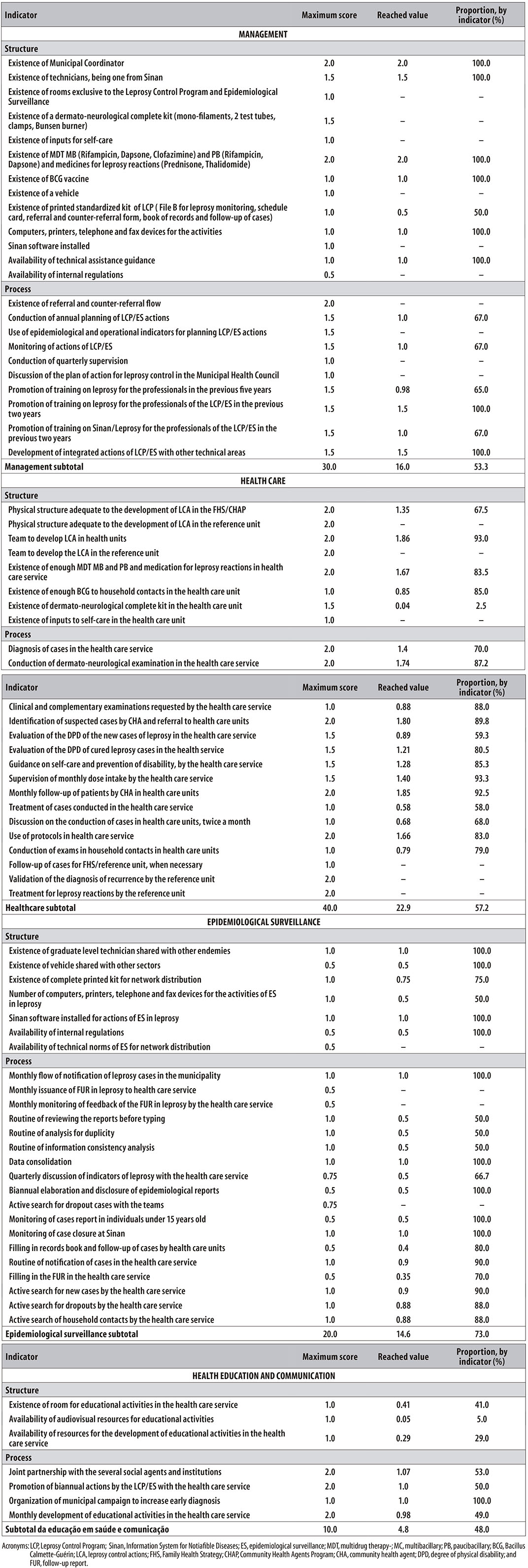

Figure 5 presents the results of MLPC by component. The indicators related to management showed to be regular (changes in professional practices of technicians and higher education levels after training, respectively, 83.0% and 88.0%) or precarious (annual plan, 50.0%; uniformity of assistance flow, 15.0%; and problems resolution, 44.0%).

The annual detection rate of new cases in 2010 and 2011 was very high (respectively, 33.2 and 22.6/100 thousand inhabitants); and in 2012, high (19.7/100 thousand inhabitants). The same rate in individuals under 15 years old, in all three years, remained very high: from 2010 to 2011, it remained in 9.0/100 thousand inhabitants; and decreased in 2012 to 5.9/100 thousand inhabitants. The proportion of new cases of leprosy with a degree of physical disability assessed by diagnosis varied from 82.8% to 91.0%; the ratio of cure of new cases diagnosed in the years assessed varied between 24.0 and 73.0%. The proportion of dropout cases remained precarious in 2010 (33%), in 2011 (69.5%) and 2012 (34.1%). As for the quality of information, the consistency varied from 81.0 to 91.0%; and the absence of duplicates remained at 100.0% in all three years. For timely closure of cases, it varied from 70.3 to 78.4% (Figure 5).

The result indicators related to health education and communication were classified as precarious (promotion of social mobilization activity, 50.0%; and behavior of users after participation in activities of prevention, 59.0%) (Figure 5).

Discussion

The analysis of the Municipal Leprosy Control Program has exposed operational, technical and administrative obstacles, as already demonstrated in previous studies,6,7 characterizing its degree of implementation in Camaragibe as ‘incipient’. After nearly four decades after the recommendation of multidrug therapy by WHO, almost three after its formalization in Brazil,13 and nearly two decades since the beginning of the process of decentralization of LCA to the Primary Health Care, it would be expected further progress regarding the implementation actions and the effects observed. Among the main critical points that contributed to the situation found, we should highlight: absence of referral service; low management autonomy and resolution; fragility of the information system; precariousness of epidemiological surveillance actions and educational activities; and little joint efforts with social and institutional agents.

The methodological approach used - a single case study - is described as having high potential of internal validity, by analyzing in depth a phenomenon, allowing the program’s functioning to be described and explained broadly, without sticking to specific issues about the object of evaluation.9 The quality of theoretical articulation of the model relates to the internal validity of the study.10 The construct of the Leprosy Control Program is well established, based on biomedical research and interventions applied in large scale.

The limitations of this research, inherent to single-case studies, relate to the excess of indicators in relation to the observation scores. Similarly, in this type of study we question the external validity, although what is sought is not the statistical generalization, but the analytical, based on the Logical Model of the program, that is, the extrapolation of the adopted model and not the empirical results.10

The inadequacy of the program's management in the municipal scope relates, among other aspects, to the insufficiency of monitoring process and epidemiological and operational indicators, of systematic evaluation of LCA and teams' supervision, besides the lack of annual planning of actions and dialogue with social control institutions. Similar findings to those highlighted were evidenced in evaluations of the Leprosy Control Program and the performance of Primary Health Care.14-16

Also, the weak management preparation, associated with the vertical municipal management and the lack of service integration, influence the program's condition, which becomes improvised, with low resolution of municipal services, as observed in another context.17 In order to minimize such difficulties, it is suggested an accurate definition of attributions, improvement of communication between the several departments and sharing of responsibilities.18

Despite the low investment of management in the promotion of leprosy training among the health professionals, it was observed a change in their practices. Also, during the assessment of the role of training in the quality of LCA, it was found that the positive differential was the teaching/learning process and the commitment of professionals.19 In a study conducted in Recife, in 2013, the training courses were analyzed from the professionals' perspectives, and it was revealed a need to negotiate the content and methodology from the problematization of the work, aiming at a better performance.20 In spite of that, there are no guarantees of a proactive professional profile and transformation of the health care model.21

The influence of the implementation degree of the effects observed, by component, was convergent and divergent between some indicators, especially among the unsatisfactory: (i) low proportion of contacts examined, (ii) treatment dropout, (iii) limited standardization of patient care flow, and (iv) inadequate resolution of issues with management support. A previous study carried out in the same municipality almost a decade before (2004), showed divergences between the degree of implementation of strategic areas of Primary Health Care and the operational epidemiological indicators of the program,22 similar to what was observed on the National Program.7

The rates of general detection and in individuals under 15 years of age showed very high endemicity, although the diagnostic activities were adequate, pointing out not only the increase of coverage of the health care system and diagnostic speed, but also - and mainly - expansion of the disease, reflecting a higher incidence of new cases.23,24 However, the high indicator in individuals under 15 years shows a persistence of transmission and precocity of exposure to active sites, suggesting a deficiency in surveillance and disease control.24 Most part of structure indicators of MLPC were deficient, which is a bottleneck and compromises the quality of assistance. Furthermore, when there is suspicion of the case, the referral to another service is frequent, which hampers early diagnosis and timely treatment. Reports about the lack of physicians in Primary Health Care, low professional commitment, deficient technical and scientific quality and inadequate performance are re-incident, overwhelming nurses, in addition to the transfer of responsibilities and blurring of roles.25,26

There are frequent reports about users in treatment or discharged from MLPC, who have not been evaluated for their degree of physical disability, perhaps due to the unfamiliarity, for many professionals, of the classification technique and its importance as a strategy to prevent disabilities.27 The analysis of degree of implementation of health assistance in the current study showed to be incipient. However, the indicators related to the level of physical disability in diagnosis ranged from regular to good during the three years studied, probably because some patients were evaluated according to State references, leaving the primary care in charge of notifying and starting treatment.

There was good evaluation regarding the active search for household contacts and dropout patients. Nonetheless, these procedures were not enough to ensure the high proportion of contacts examined and reverse the abandonment of treatment among newly diagnosed cases. The examination of contacts is essential to early discover new cases, guide about the signs of the disease and break of the chain of transmission.24 Similarly, other authors observed that a reduced number of contacts have received such measure, whilst the intake of medication for several months and the appearance of leprosy reactions are possible explanations to dropouts or irregularity in treatment.28

In spite of the highlighted results, it is important to consider the quality of information of Sinan related to the consistency and existence of duplicity, because it could compromise the analysis of indicators.14 The precarious conduction of these procedures by the municipality was not detected in the indicators due to the implementation, by the State Health Department, of emergency actions aiming to improve the quality of information from the public Sinan.

As the reference unit was not working the users were referred to other specialized services, located in other municipalities, adding barriers to access, such as cost and difficulties to schedule medical visits.28 Finally, the promotion actions, such as health education and communication, are effective strategies for a good performance of programs related to neglected diseases, though they are demoted, according to findings of this study. When these actions take place, they are predominantly vertical and unilateral, emphasizing campaigns and production of educational material29 in detriment to social and pedagogical practices developed by the team in partnership with social and institutional agents.21,28 This practice must be focused on community participation, allied to experience with the disease and its’ inclusion in the planning, execution and evaluation of actions. Thus, it is possible to favor changes in behavior, individual and collective health promotion and improve the community quality of life.30

In 2013, the Camaragibe MLPC presented an incipient degree of implementation in the municipality, with repercussions on the results achieved and here analyzed. The activities of health education and communication, as well as the program’s management and health assistance, are more problematic, whereas the epidemiological surveillance is better structured. For the effective control of leprosy, it is necessary to overcome such difficulties, with greater mobilization of resources and enough investments to qualify municipal health care network, the reorganization of services and strengthening of the health information system.

REFERENCES

1. Tavares APN, Marques RC, Lana FCF. Ocupação do espaço e sua relação com a progressão da hanseníase no Nordeste de Minas Gerais - século XIX. Saude Soc. 2015 abr-jun;24(2):691-702. [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014 89(36):389-400. [ Links ]

3. Alencar CH, Ramos Jr AN, Santos ES, Richter J, Heukelbach J. Clusters of leprosy transmission and of late diagnosis in a highly endemic area in Brazil: focus on different spatial analysis approaches. Trop Med Int Health. 2012 Apr;17(4):518-25. [ Links ]

4. Secretaria Estadual de Saúde (Pernambuco). Boletim hanseníase. Recife: Secretaria Executiva de Vigilância em Saúde; 2013. [ Links ]

5. Opromolla PA, Laurenti R. Controle da hanseníase no Estado de São Paulo: análise histórica. Rev Saúde Pública. 2011 fev;45(1):195-203. [ Links ]

6. Lustosa AA, Nogueira LT, Pedrosa JIS, Teles JBM, Campelo V. The impact of leprosy on health-related quality of life. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011 Sep-Oct; 44(5):621-6. [ Links ]

7. Raposo MT, Nemes MIB. Assessment of integration of the leprosy program into primary health care in Aracaju, state of Sergipe, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012 Mar-Apr;45(2):203-8. [ Links ]

8. Leal DR, Cazarin G, Bezerra LCA, de Albuquerque AC, Felisberto E. Programa de controle da hanseníase: uma avaliação da implantação no nível distrital. Saúde Debate. 2017 mar;38(Esp):209-228. [ Links ]

9. Champagne F, Brousselle A, Hartz ZMA, Contandriopoulos AP, Denis JL. A análise de implantação. In: Brousselle A, Champagne F, Contandriopoulos AP, Hartz ZMA, organizadores. Avaliação, conceitos e métodos. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2011. p. 217-38. [ Links ]

10. Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2009. [ Links ]

11. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Estimativa populacional para 2012. Brasília, 2012 . Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/estimativa2012/ [ Links ]

12. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Relatório de gestão da coordenação geral do programa nacional de controle da hanseníase: janeiro de 2009 a dezembro de 2010. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2011. [ Links ]

13. Eidt LM. Breve história da hanseníase: sua expansão do mundo para as Américas, o Brasil e o Rio Grande do Sul e sua trajetória na saúde pública brasileira. Saúde Soc. 2004 maio-ago;13(2):76-88. [ Links ]

14. Galvão PR, Ferreira AT, Maciel MD, De Almeida RP, Hinders D, Schreuder PA, Kerr-Pontes LR. An evaluation of the SINAN health information system as used by the hansen’s disease control programme, Pernambuco State, Brazil. Lepr Rev. 2008 Jun;79(2):171-82. [ Links ]

15. Facchini LA, Piccini RX, Tomasi E, Thumé E; Silveira DS, Siqueira VF, et al. Desempenho do PSF no Sul e no Nordeste do Brasil: avaliação institucional e epidemiológica da Atenção Básica à Saúde. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2006 jul-set; 11(3):669-81. [ Links ]

16. Almeida PF, Fausto MCR, Giovanella L. Fortalecimento da atenção primária à saúde: estratégia para potencializar a coordenação dos cuidados. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011 fev;29(2):84-95. [ Links ]

17. Lanza FM, Lana FCF. Decentralization of leprosy control actions in the micro-region of Almenara, State of Minas Gerais. Rev Latino-Am Enferm. 2011 Jan-Feb; 19(1):187-94. [ Links ]

18. Oliveira MM, Campos GWS. Matrix support and institutional support: analyzing their construction. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015 Jan;20(1):229-38. [ Links ]

19. Lima MSM, Pomini ACM, Hinders D, Soares MPB, Mello MGS. Capacitação técnica versus comprometimento profissional: o real impacto no controle da hanseníase. Cad Saúde Colet. 2008 abr-jun;16(2):293-308. [ Links ]

20. Souza ALA, Feliciano KVO, Mendes MFM. Family Health Strategy professionals' view on the effects of Hansen's disease training. Rev Esc Enferm. 2015 Jul-Aug;49 (4):610-18. [ Links ]

21. Pereira AJ, Helene LMF, Pedrazini ES, Martins CL, Vieira CSCA. Atenção básica de saúde e a assistência em hanseníase em serviços de saúde de um município do Estado de São Paulo. Rev Bras Enferm. 2008 nov;61(Esp):718-26. [ Links ]

22. Cavalcante MGS, Samico I, Frias PG, Vidal SA. Análise de implantação das áreas estratégicas da atenção básica nas equipes de Saúde da Família em município de uma região metropolitana do Nordeste brasileiro. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Infant. 2006 out-dez;6(4):437-45. [ Links ]

23. Penna MLF, Oliveira MLW, Carmo EH, Penna GO Temporão JG . Influência do aumento do acesso à atenção básica no comportamento da taxa de detecção de hanseníase de 1980 a 2006. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41(Supl 2):6-10. [ Links ]

24. Pires CAA, Malcher CMSR, Abreu Júnior JMC, Albuquerque TG, Corrêa IRS, Daxbacher ELR. Leprosy in children under 15 years: the importance of early diagnosis. Rev Paul Pediatr 2012 Jun;30(2):292-5. [ Links ]

25. Vanderlei LCM, Vázquez-Navarrete ML. Mortalidade infantil evitável e barreiras de acesso à atenção básica no Recife, Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2013 abr;47(2):379-89. [ Links ]

26. Rodrigues FF, Calou CGP, Leandro TA, Antezana FJ, Pinheiro AKB, Silva VM, Alves MDS. Knowledge and practice of the nurse about leprosy: actions of control and elimination. Rev Bras Enferm. 2015 Mar-Apr;68(2):271-7. [ Links ]

27. Silva Sobrinho RA, Mathias TAF, Gomes EA, Lincoln PB. Avaliação do grau de incapacidade em hanseníase: uma estratégia para sensibilização e capacitação da equipe de enfermagem. Rev Latino-Am Enferm. 2007 nov-dez;15(6):1125-30. [ Links ]

28. Arantes CK, Garcia MLR, Filipe MS, Nardi SMT, Paschoal VD. Avaliação dos serviços de saúde em relação ao diagnóstico precoce da hanseníase. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2010 abri-jun;19(2):155-64. [ Links ]

29. Kelly-Santos A, Rosemberg B, Monteiro, S. Significados e usos de materiais educativos sobre hanseníase segundo profissionais de saúde pública do município do Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009 jan-abr;25(4):857-67. [ Links ]

30. Souza LB, Aquino PS, Fernandes JFP, Vieira NFC, Barroso MGT. Educação, cultura e participação popular: abordagem no contexto da educação em saúde. Rev Enferm UERJ. 2008 jan-mar;16(1):107-12. [ Links ]

*Article originated from Monique Feitosa de Souza’s Master’s thesis in Health Assessment, entitled ‘Evaluation of the Implementation of the Leprosy Control Program in Camaragibe, Pernambuco,’ defended at the Post-graduation Program in Health Assessment of the Institute of Comprehensive Medicine Professor Fernando Figueira, in 2014.

Received: April 30, 2017; Accepted: June 17, 2017

texto em

texto em