Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versión impresa ISSN 1679-4974versión On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.27 no.2 Brasília jun. 2018 Epub 03-Mayo-2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742018000200010

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Characterization of sexual violence against children and adolescents in school - Brazil, 2010-2014

1Universidade Federal do Piauí, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde e Comunidade, Teresina, PI, Brasil

2Universidade de São Paulo, Departamento de Medicina Social, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil

Objective:

to describe the reports of sexual violence against children and adolescents at school, in Brazil, from 2010 to 2014.

Methods:

a descriptive study on the characteristics of the victims, the event, the aggressor and the attendance among the records of compulsory notification of sexual violence against children (0-9 years) and adolescents (10-19 years) at school; we used data from the Notification of Injury Information System (Sinan).

Results:

2,226 reports of sexual violence occurred at school, of which 1,546 (69.5%) were children and 680 (30.5%) were adolescents; the average age of the victims was 7.4 years and the median age was 6 years; prevalence of female victims (63.8%) and, most of the time, the aggressor was male (88.9%).

Conclusion:

children and adolescents are exposed to sexual violence at school, a place that supposedly should guarantee protection, healthy development and safety for schoolchildren.

Keywords: Sex Offenses; Mandatory Reporting; School Health; Child Abuse, Sexual; Epidemiology, Descriptive

Introduction

Violence has been present throughout the history of humankind, affecting all social classes and segments. It leads to a reduction in the quality of life of individuals and societies, constituting a serious public health problem at the global level.1 Among the different types of violence, sexual abuse is a constant concern, since it often occurs in the school environment.2 It is estimated that, annually, about 40 million children and adolescents suffer sexual abuse worldwide. However, this figure may be underestimated due to the circumstances in which these events occur, the dependency relationship between the victims and the abuser, as well as the fear and embarrassment related to difficulties in denouncing this type of violence.3

Psychological sequels, such as low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, anger, aggression, post-traumatic stress, sexual difficulties, suicidal thoughts, and low school performance, can be found in young adults with a history of sexual violence.4 The violence suffered by children and adolescents can also have an impact on their families, on future relationships, and on the social environment in which they live.

Therefore, it affects both individual and collective health. Since it is a complex phenomenon and is of great magnitude, sexual violence against children and adolescents requires special attention from public health authorities and a comprehensive response.5

In Brazil, the results of the 2015 National Adolescent School-based Health Survey (PeNSE)6 showed that 4.0% of interviewed students reported having been forced to have sexual intercourse, ranging from 3.7% in boys to 4.5% in girls. According to data from the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN), sexual violence ranked second among the aggressions against adolescents aged 10 to 19 years, accounting for 23.9% of all notifications, and being exceeded only by physical violence, which accounts for 63.3% of all notifications.7

The interest in identifying violence, including sexual abuse, in the school context is growing, not only because of its implications in the process of child and adolescent integration in society, but also because of its relation to the school's failure in achieving broader goals, such as educating, teaching and learning.8

For the purposes of epidemiological surveillance, sexual violence is defined as:

Any action in which a person, taking advantage of their position of power and making use of physical force, coercion, intimidation or psychological influence, with the use or not of weapons or drugs, obliges another person - of either sex - to have, witness, or participate in any way of sexual interactions or use in any manner, their sexuality, with the purpose of profit, vengeance or another intention.9

Although studies3,6,7 have described the characteristics of the occurrence of sexual violence against children and adolescents in Brazil, few publications8 have addressed this type of abuse specifically in the school environment.

Given the current interest in the occurrence of sexual abuse in the school environment, and considering that it constitutes an object for monitoring and surveillance by the health sector, this study aimed to describe the reports of sexual violence against children and adolescents at school, in Brazil, during 2010 -2014.

Methods

This is a descriptive study of cases of sexual violence committed against children aged 0 to 9 years and adolescents aged 10 to 19 years in the school environment, across the Brazilian territory, during 2010-2014.

Data from the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) were used. In Brazil, the Violence and Accidents Surveillance System (VIVA System) was established in 2006. The VIVA System is comprised of two components: one is focused on care for victims of accidents and violence at emergency health services and carried out through surveys(VIVA Survey), while the other provides continuous surveillance of interpersonal and self-inflicted violence identified in health services (VIVA SINAN). Since 2009, cases of violence and accidents are registered on SINAN; however, violence was only included in the National List of Compulsory Notifiable Diseases from 2011 onwards, and compulsory notification became universal countrywide. The individual notification form must be used for notification of any suspected or confirmed case of domestic/intrafamily, sexual or self-inflicted violence, trafficking in persons, slavery, child labor, torture, legal intervention and homophobic violence against women and men of all ages.9

The form for notification of interpersonal violence and intentional self-inflicted injury is composed of variables grouped in blocks, as follows: general data; individual notification; residence data; personal information of the victim; data about the incident; violence; sexual violence; data of the likely perpetrator of violence; arrangements made; and final data. These forms are input to SINAN by the Municipal Health Secretariats and the data are transferred to the state and federal levels, to compose the municipal, state and national databases.9

All cases of sexual violence against children and adolescents at school were selected from the SINAN database, based on the following criteria: (i) type of sexual violence; (ii) age of the victim - 0 to 19 years; and (iii) place of occurrence - School (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Flowchart for identification of records that met the definition of cases of sexual violence against children and adolescents occurring at school, on the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN), Brazil, 2010-2014

The cases were analyzed according to the following characteristics:

The victims

- age (in years: 0 to 9; 10 to 19);

- sex (male; female);

- ethnicity/skin color (white; black and brown; other

- yellow and indigenous);(B) The event

- repeated violence (if already occurred before); and

- type of sexual violence (Rape; Sexual harassment; indecent assault; sexual exploitation; pornography; other);

C) The aggressor(s)

- sex (male; female; both sexes, when more than one perpetrator of different sexes);

- if the victim suspected that the likely perpetrator of aggression had ingested alcoholic drink (no; yes); and

- likely perpetrator of aggression (known - family, spouse, boyfriend, friend, unknown - person without family or affective relationship with the victim); and (D) Health care provided

- procedures (blood collection; prophylaxis against sexually transmitted infections; prophylaxis against HIV; collection of vaginal secretion; prophylaxis against hepatitis B; Emergency contraception; semen collection; legal abortion );

- evolution (discharge; evasion/escape);

- referring the victim to other services (Tutelary Council, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Child and Adolescent Protection Police; other police; Reference Center specialized in Social Assistance; Women's Police Station; Child and Youth Court; the Sentinel Program; Public Prosecution Service; Women's Reference Center; shelter; others) Associations were tested using the Pearson chi-square test (X2), with a significance level of 5%. The statistical analyses were carried out using Stata® version 14.

The technical team of the Department of Surveillance of Noncommunicable Diseases and Health Promotion of the Ministry of Health (DANTPS/SVS/MS) provided the national dataset, which had previously undergone a consistency analysis and duplicate records were excluded.

The anonymity and confidentiality of record information was preserved. Since this is a study based on anonymous secondary data, this research project was exempted from appreciation by the Committee for Ethics in Research, in accordance with National Health Council (CNS) Resolution n° 510, dated April 7, 2016.

Results

A total of 2,226 notifications of sexual violence at school against children and adolescents was registered in Brazil during 2010-2014. Most victims were female (63.8%) and white (51.8%).

Approximately one third of the cases (34.7%) referred recurrence of violence. Rape (60.9%) was the most frequent type of sexual violence, followed by the sexual harassment (29.7%) and indecent assault (21.6%). The majority of the victims was assaulted by male individuals (88.9%) and by acquaintances of the victim (46.0%). In only 7.1% of all notifications, the victims suspected that the probable aggressors had drunk alcohol. Regarding the care provided, 25.3% of victims had blood collected, 96.9% were discharged and 73.8% were referred to the Tutelary Council (Table 1).

Table 1 - Distribution of reports of sexual violence against children and adolescents occurring at school, according to characteristics of the victim, the event, the aggressor and the care provider, Brazil, 2010-2014

| Characteristics | Children (0-9 years) (N=1,546; 69.5%) | Adolescents (10-19 years) (N=680; 30.5%) | Totala (N=2,226; 100.0%) | p-valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| The Victim | |||||||

| Sex (N=2,226) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Female | 897 | 58.0 | 524 | 77.1 | 1,421 | 63.8 | |

| Male | 649 | 42.0 | 156 | 22.9 | 805 | 36.2 | |

| Ethnicity/skin color (N=1,906) | <0.001 | ||||||

| White | 742 | 57.1 | 245 | 40.4 | 987 | 51.8 | |

| Black | 543 | 41.8 | 343 | 56.5 | 886 | 46.5 | |

| Other | 14 | 1.1 | 19 | 3.1 | 33 | 1.7 | |

| The event | |||||||

| Repeated violence (N=1,566) | 0.001 | ||||||

| No | 696 | 68.2 | 327 | 60.0 | 1,023 | 65.3 | |

| Yes | 325 | 31.8 | 218 | 40.0 | 543 | 34.7 | |

| Type of sexual violence c | |||||||

| Rape | 713 | 56.1 | 440 | 70.9 | 1,153 | 60.9 | <0.001 |

| Sexual harassment | 356 | 27.9 | 202 | 33.4 | 558 | 29.7 | 0.014 |

| Indecent assault | 283 | 24.1 | 88 | 16.2 | 371 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| Sexual exploitation | 41 | 3.3 | 24 | 4.1 | 65 | 3.5 | 0.380 |

| Child pornography | 28 | 2.3 | 22 | 3.8 | 50 | 2.7 | 0.065 |

| Others | 132 | 10.8 | 28 | 5.0 | 160 | 9.0 | <0.001 |

| The Aggressor | |||||||

| Sex of the Aggressor (N=1,924) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 1,087 | 85.5 | 624 | 95.7 | 1,711 | 88.9 | |

| Female | 159 | 12.5 | 12 | 1.8 | 171 | 8.9 | |

| Both sexes | 26 | 2.0 | 16 | 2.5 | 42 | 2.2 | |

| Suspicion that the offender has ingested alcoholic drink (N=1,289) | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 843 | 96.9 | 355 | 84.7 | 1,198 | 92.9 | |

| Yes | 27 | 3.1 | 64 | 15.3 | 91 | 7.1 | |

| Probable author of aggression c | |||||||

| Known | 618 | 46.9 | 274 | 44.1 | 892 | 46.0 | 0.248 |

| Unknown | 202 | 15.7 | 156 | 25.6 | 358 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Health Care | |||||||

| Procedures c | |||||||

| Blood collection | 234 | 19.8 | 204 | 37.3 | 438 | 25.3 | <0.001 |

| Prophylaxis against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) | 111 | 9.5 | 143 | 26.3 | 254 | 14.8 | <0.001 |

| Prophylaxis against HIV | 93 | 8.0 | 138 | 25.4 | 231 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| Collection of vaginal secretions | 48 | 7.4 | 73 | 17.9 | 121 | 11.4 | <0.001 |

| Prophylaxis against hepatitis B | 58 | 5.0 | 107 | 19.9 | 165 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Emergency contraception | 7 | 1.1 | 94 | 22.7 | 101 | 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Semen collection | 16 | 1.4 | 31 | 5.9 | 47 | 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Legal abortion | - | - | 5 | 1.3 | 5 | 1.1 | - |

| Evolution (N=1,517) | 0.491 | ||||||

| Discharged | 1,038 | 97.1 | 432 | 96.4 | 1,470 | 96.9 | |

| Avoidance/Escape | 31 | 2.9 | 16 | 3.6 | 47 | 3.1 | |

| Referral to other sectors c | |||||||

| Tutelary Council | 1,031 | 77.5 | 375 | 65.2 | 1,406 | 73.8 | <0.001 |

| Institute of Forensic Medicine | 344 | 27.1 | 144 | 26.1 | 488 | 26.8 | 0.660 |

| Child and Adolescent Protection Police | 298 | 23.7 | 135 | 24.8 | 433 | 24.0 | 0.634 |

| Other Polices | 212 | 16.9 | 100 | 18.2 | 312 | 17.3 | 0.481 |

| Reference Center Specialised in Social Assistance | 202 | 16.1 | 104 | 18.8 | 306 | 16.9 | 0.159 |

| Women's Police | 116 | 9.2 | 68 | 12.4 | 184 | 10.2 | 0.043 |

| Childhood and Adolescence Law Court | 57 | 4.6 | 35 | 6.4 | 92 | 5.2 | 0.106 |

| Sentinel Program | 47 | 3.8 | 21 | 3.9 | 68 | 3.8 | 0.932 |

| Public Prosecution Service | 40 | 3.2 | 27 | 5.0 | 67 | 3.8 | 0.077 |

| Women’s Reference Center | 29 | 2.3 | 24 | 4.4 | 53 | 3.0 | 0.017 |

| Shelter | 4 | 0.3 | 8 | 1.5 | 12 | 0.7 | NA d |

| Other | 241 | 19.9 | 83 | 15.7 | 324 | 18.6 | 0.038 |

a) Totals vary due to missing data (unknown/blank)

b) Test of Pearson's chi-square

c) Does not correspond to 100%, because there could be more than one option for the same case notified.

d) NA: Not applicable - there were calculated using the Pearson chi-square test and p-value, due to the existence of cell with expected value <5.

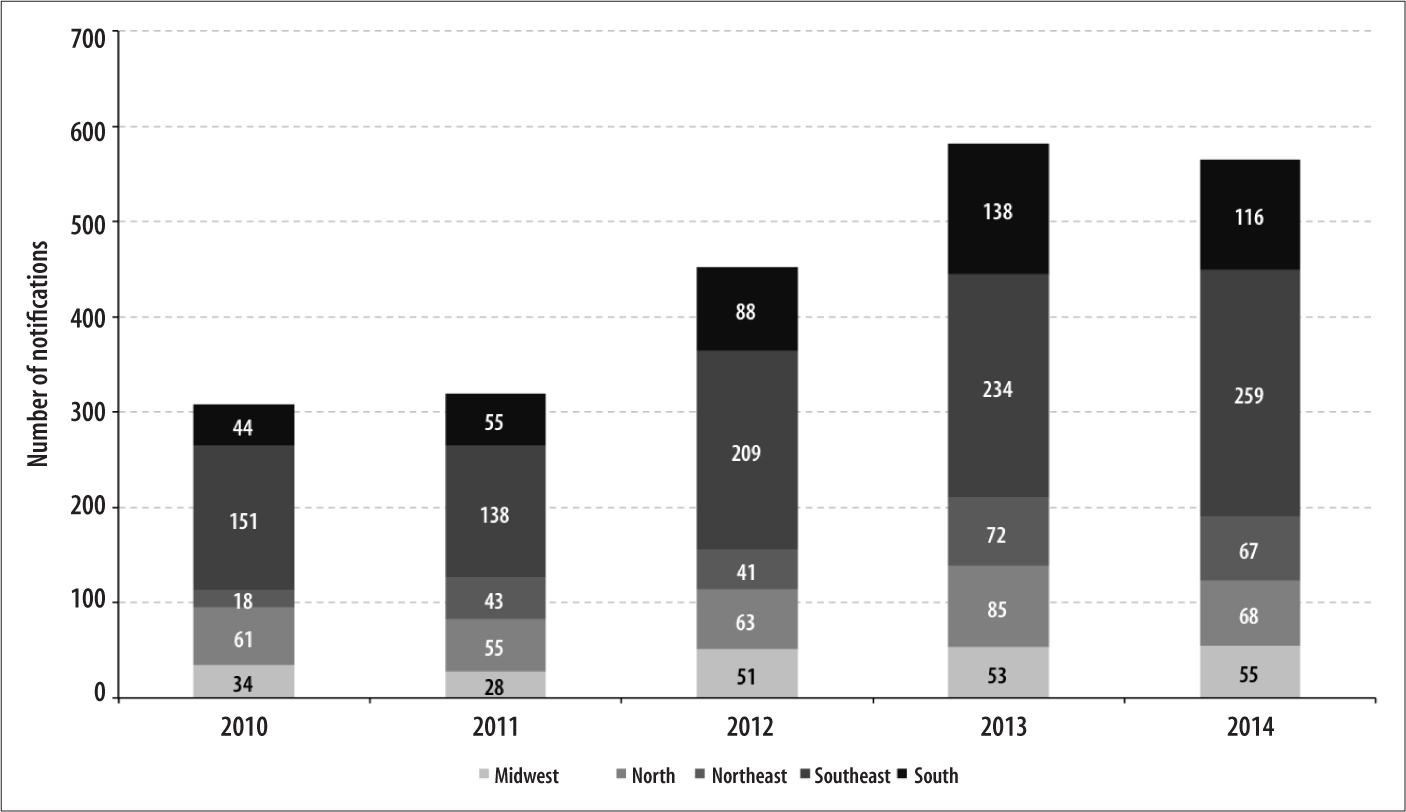

In this period, there was an increase in the number of notifications of sexual violence against children and adolescents at school, increasing from 308 in 2010 to 565 in 2014 countrywide. This growth was observed in all regions of the country (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Evolution of reports of sexual violence against children and adolescents occurring at school, according to geographic region, Brazil, 2010-2014

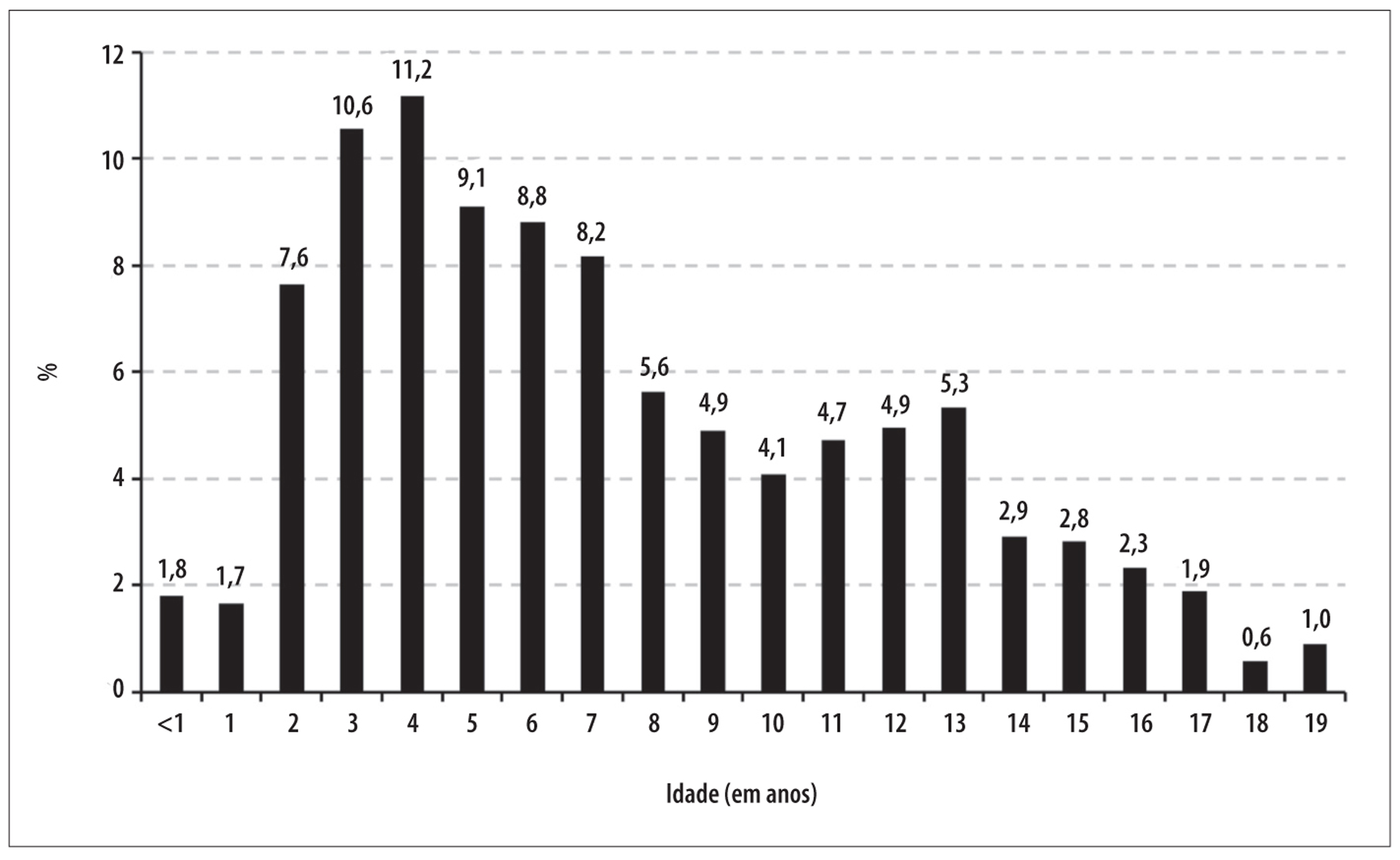

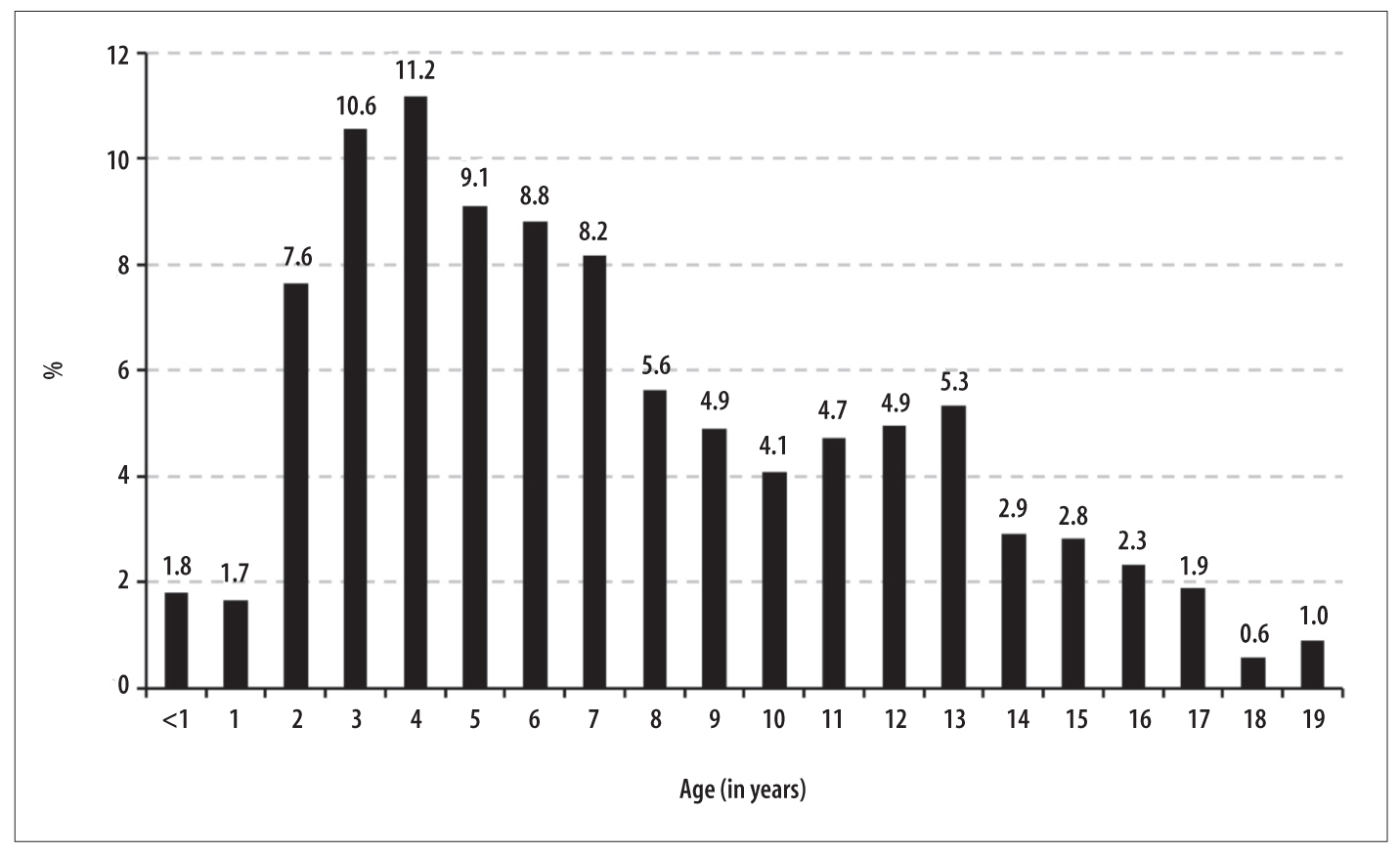

The age group of 3 to 6 years concentrated 39.7% of notifications (Figure 3). The average age of the victims was 7.4 years (standard deviation: 4.5), with a median age of 6 years old.

Figure 3 - Proportional distribution of reports of sexual violence against children and adolescents occurring at school, according to age of the victim, Brazil, 2010-2014

The notified cases were concentrated in the 0 to 9 years age group (69.5%), while the cases among adolescents aged 10-19 years comprised 30.5% of the notifications. The proportion of female victims (77.1%) and those with black skin color (56.5%) was significantly higher among adolescents (p<0.001)(Table 1).

There was a greater proportion of recurrence of sexual violence against adolescents at school (40.0%) in comparison with children (31.8%) (p=0.001). The cases of rape (70.9%; p<0.001) and sexual harassment (33.4%; p=0.014) were more frequent among adolescents, while the notifications of indecent assault prevailed among children (24.1%; p<0.001). The cases perpetrated by males were more frequent, mainly against adolescents (95.7%; p<0.001). Intake of alcohol by the abuser was five times more frequent in cases against adolescents compared to those against children (15.3%; p<0.001). The aggressor was, in most cases, a person known to the victim in both age groups. Aggression by individuals unknown to the victim was reported in a greater proportion among adolescents (25.6%; p<0.001) (Table 1).

Health care procedures related to the collection of clinical samples and prophylaxis of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were indicated, to a greater extent, among victims aged 10 to 19 years (p <0.001). In the two age groups analyzed, the proportion of discharge was greater than 96%. The Tutelary Council was the institution that received the largest percentage of referrals, mainly among the victims under 10 years of age (77.5%; p<0.001) (Table 1).

Discussion

This study shows that children and adolescents are exposed to sexual violence at school, an institution

which, supposedly, should ensure protection, healthy development and security for students. This article comprises the first national study of sexual violence in the school environment.

It should be emphasized that although several studies6.12-14 are cited in this article, none refers to sexual violence at school but only to sexual violence reported by students or by adolescents of school age that could have happened anywhere. This article unveils a problem capable of triggering several consequences for children and adolescents, such as isolation, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, low school performance among others, due to their emotional, cognitive and social abilities being less mature.11

The results of this study show the gradual increase in the number of reports of sexual violence occurring at school, in all regions of Brazil, over the period from 2010 to 2014. The global prevalence of sexual abuse against children and adolescents varies between 8-31% for girls and 3-17% for boys, and continues to worry the public authorities and society in general.12 A study on risk behaviors among young students in the United States of America in 201513 showed that 6.7% of the participants had been forced to have sexual relations. The study also revealed that the prevalence of sexual violence among students was almost three times higher in females (15.6%) in relation to males (5.4%).

In a study conducted in Brasilia-DF, in 2012, with children aged 11 to 15 years enrolled in public schools, it was possible to identify high occurrence of physical violence (85.4% prevalence), followed by psychological violence (62.5%) and sexual violence (34.7%).14 Given the magnitude of these findings, the need to investigate sexual violence within the school environment is reinforced, as well as the deleterious effects that this type of violence may have on the development of the individual.

Of the total cases reported, it was observed that female children and adolescents are more likely to suffer sexual violence at school, which is consistent with a study carried out in Campo Grande-MS, during 2007-2008, that pointed to the female sex as the group most affected by sexual violence, especially during adolescence.15 Other studies demonstrate that the risk of sexual violence is twice higher among women compared to men.16 Also, 10-20% of girls and 5-10% of boys have suffered sexual violence before the age of 18 years.12

In a study carried out among school adolescents in the United States of American,17 30% of respondents showed victimization through sexual harassment, 37% in women and 21% in men. Other studies showed that perpetrators of sexual violence were more commonly intimate partners, family members and teachers.18-20 These findings are similar to the results of this study in relation to the probable perpetrators of aggression, which, in their majority, were known to the family.

With regard to care for children and adolescents victims of sexual violence at school, the role played by the Tutelary Councils deserves special mention. According to article 131 of the Statute for Children and Adolescents, 'the Tutelary Council is a permanent and autonomous organ, non-judicial, made responsible by society to ensure the fulfilment of the rights of the child and adolescent'. Because of this assignment, schools refer sexual violence cases identified to the Tutelary Councils for the necessary measures to be taken. The Councils, in turn, redirect cases to other components of the sexual violence care and coping network.21

In relation to the types of sexual violence, rape, sexual harassment, indecent assault, sexual exploitation, child pornography and others were identified. It was observed that, among the types of sexual violence, rape was the most frequent, possibly related to the fact that other types of sexual violence are not recognized as violence. It seems to be more difficult for children to define harassment, indecent, pornography and other types of violence, and this hinders complaints and/or explanation of the facts. On the other hand, rape is a form of sexual violence, and for this reason, triggers complaints, which is something that may not occur with other types of violence.22

Given this scenario, efforts are being made to minimize sexual violence and encourage complaints, such as, for example: enactment of the Statute for Children and Adolescents (ECA), in 1990;23 the campaign for the prevention of accidents and violence in childhood and adolescence, established by the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics in 1998; elaboration of the National Plan for the Combat of Sexual Violence against Children and Adolescents, by the Ministry of Justice, in 2000; and implementation by the Ministry of Health of National Policy on Reducing Mortality from Accidents and Violence (Ordinance No 737/2001);24 as well as the National Health Promotion Policy (Decree No. 687/2006)25 and the deployment of the Childhood and Adolescence Information System (SIPIA) in 2002, which enables a national system of continuous monitoring of the situation of children and adolescents under Tutelary Council protection, thus providing, with agility and speed, information to various bodies (municipal, state and federal level).3

In the 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the concept and encouraged Health Promoting Schools. Because of this initiative, in 2008, more than 100 countries were already monitoring the health of students, helping to modify curricula and structuring health programs aimed at the adolescent age group.26

In Brazil, since 2004 the Federal Government has been developing theSchool that Protects project, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, aimed at expanding dialog with society and articulating the means to protect children and adolescents from different types of violence."27 In addition, the Federal Government deployed the Health at School Program (PSE), instituted by Decree No. 6286, dated 5 December 2007, having as one of its goals the promotion of health and the culture of peace, strengthening the prevention of health problems - including violence -, developing integrated actions between the health and education sectors.28 Schools must provide a healthy and safe environment for children to learn and develop fully, protecting them from situations that pose risks to their physical and psychological health.

Although it is essential, there is insufficient data on sexual violence at school and this hinders prevention efforts. In both cases, WHO recommends strengthening data collection in order to reveal the true extent of the problem, integrating different sectors such as health, education and justice, in addition to ensuring care services for victims. Data should be supported by evidence and inform studies intended to evaluate results. WHO also makes a further recommendation in addition to these: full implementation of existing laws dedicated to the protection of children and adolescents and to coping with this kind of violence.29

The limitations encountered in this study are proper to research based on secondary data, such as the quality of the filling-in of variables found on the notification form and the incorrect power supply system. Difficulty in obtaining the actual number of cases by means of notification may be related to the fact that those who suffer sexual violence, when affected by the stigma that blames the victim, avoid reporting the abuses suffered. As a result, the numbers reported fall short of reality.30

Despite the limitations mentioned, this article has brought important contributions by revealing, for the first time, reported sexual violence against children and adolescents in Brazilian schools. These findings are a valuable tool for planning and developing intersectorial actions to prevent violence and provide assistance to students. The results presented here can be used to guide actions that contribute to improving the monitoring and prevention of cases of sexual violence against children and adolescents at school, supporting the provision of assistance to victims and the implementation of measures for monitoring and accountability of perpetrators.

Referências

1. Minayo MCS. Conceito, teorias e tipologias de violência: a violência faz mal a saúde. In: Njaine K, Assis SG, Constantino P. (Org.). Impacto da violência na saúde [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2009 [citado 2017 nov 20]. p. 21-42. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www1.londrina.pr.gov.br/dados/images/stories/Storage/sec_mulher/capacitacao_rede%20/modulo_2/205631-conceitos_teorias_tipologias_violencia.pdf [ Links ]

2. Haile RT, Kebeta ND, Kassie GM. Prevalence of sexual abuse of male high school students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013 May;13:24. [ Links ]

3. Martins CBG, Jorge MHM. Violência contra crianças e adolescentes: contexto e reflexões sob a ótica da saúde. Londrina: Eduel; 2011. [ Links ]

4. Mekuria A, Nigussie A, Abera M. Childhood sexual abuse experiences and its associated factors among adolescent female high school students in Arbaminch town, Gammo Goffa zone, Southern Ethiopia: a mixed method study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2015 Aug;15(1):21. [ Links ]

5. Ullman SE, Peter-Hagene LC. Longitudinal relationships of social reactions, PTSD, and revictimization in sexual assault survivors. J Interpers Violence. 2016 Mar;31(6):1074-94. [ Links ]

6. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar, 2015 [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2016 [citado 2017 nov 20]. 132 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv97870.pdf [ Links ]

7. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças e Agravos Não Transmissíveis e Promoção da Saúde. Viva: sistema de vigilância de violências e acidentes: 2013 e 2014 [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017 [citado 2017 nov 20]. 218 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/viva_vigilancia_violencia_acidentes_2013_2014.pdf [ Links ]

8. Nesello F, Sant’Anna FL, Santos HG, Andrade SM, Mesas AE, Gonzáles AD. Características da violência escolar no Brasil: revisão sistemática de estudos quantitativos. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2014 abr-jun;14(2):119-36. [ Links ]

9. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Análise de Situação de Saúde. Viva: instrutivo notificação de violência interpessoal e autoprovocada. [Internet]. 2. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2016. [citado 2017 nov 20]. 92 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/viva_instrutivo_violencia_interpessoal_autoprovocada_2ed.pdf [ Links ]

10. Stata Corp. Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station (TX): Stata Corp LP; 2015. [ Links ]

11. Nooner KB, Linares LO, Batinjane J, Kramer RA, Silva R, Cloitre M. Factors related to posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012 Jul;13(3):153-66. [ Links ]

12. Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2013 Jun;58(3):469-83. [ Links ]

13. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016 Jun;65(6):1-174. [ Links ]

14. Ribeiro IMP, Ribeiro AST, Pratese R, Gondolf L. Prevalência das várias formas de violência entre escolares. Acta Paul Enferm. 2015 jan-fev;28(1):54-9. [ Links ]

15. Justino LCL, Ferreira SRP, Nunes CB, Barbosa MAM, Gerk MAS, Freitas SLF. Violência sexual contra adolescente: notificações nos conselhos tutelares, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2011 dez;32(4):781-7. [ Links ]

16. Kwako LE, Noll JG, Trickett PK. Childhood sexual abuse and attachment: an intergenerational perspective. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010 Jul;15(3):407-22. [ Links ]

17. Clear ER, Coker AL, Cook-Craig PG, Bush HM, Garcia LS, Williams CM, et al. Sexual harassment victimization and perpetration among high school students. Violence Against Women. 2014 Oct;20(10):1203-19. [ Links ]

18. Jemal J. The child sexual abuse epidemic in Addis Ababa: some reflections on reported incidents, psychosocial consequences and implication. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012 Mar;22(1):59-66. [ Links ]

19. Kisanga F, Nystrom L, Hogan N, Emmelin M. Child sexual abuse: community concern in urban Tanzania. J Child Sex Abuse. 2011 Mar;20(2):196-217. [ Links ]

20. Shimekaw B, Megabiaw B, Alamrew Z. Prevalence and associated factors of sexual violence among private college female students in Bahir Dar city, North Western Ethiopia. Health. 2013 Jun;5(6):1069-75. [ Links ]

21. Deslandes SF, Campos DS. A ótica dos conselheiros tutelares sobre a ação da rede para a garantia da proteção integral a crianças e adolescentes em situação de violência sexual. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015 jul;20(7):2173-82. [ Links ]

22. Oliveira JR, Costa MCO, Amaral MTR, Santos CA, Assis SG, Nascimento OC. Violência sexual e coocorrências em crianças e adolescentes: estudo das incidências ao longo de uma década. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2014 mar;19(3):759-71. [ Links ]

23. Brasil. Casa Civil. Lei nº 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Dispõe sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília (DF), 1990 jul 16; Seção 1:13563. [ Links ]

24. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria MS/GM nº 737, de 16 de maio de 2001. Política Nacional de Redução da morbimortalidade por acidentes e violência. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília (DF), 2001 maio 18; Seção 1:3. [ Links ]

25. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 687, de 30 de março de 2006. Aprova a Política Nacional de Promoção da Saúde. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília (DF), 2006 mar 31; Seção 1:138. [ Links ]

26. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa nacional de saúde do escolar, 2012 [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE ; 2013 [citado 2017 nov 20]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv64436.pdf [ Links ]

27. Faleiros VP, Faleiros ES. Escola que protege: enfrentando a violência contra crianças e adolescentes [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Educação, Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade; 2007[citado 2017 nov 20]. 100 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=638-vol-31-escqprotege-elet-pdf&Itemid=30192 [ Links ]

28. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. Saúde na escola [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2009 [citado 2017 nov 20]. 96 p. (Cadernos de Atenção Básica; n. 24). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/cadernos_atencao_basica_24.pdf [ Links ]

29. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Relatório mundial sobre a prevenção da violência 2014 [Internet]. São Paulo: Núcleo de Estudos da Violência; 2015 [citado 2017 nov 20]. 274 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://nevusp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/1579-VIP-Main-report-Pt-Br-26-10-2015.pdf [ Links ]

30. DeLoveh HL, Cattaneo LB. Deciding where to turn: a qualitative investigation of college students’ helpseeking decisions after sexual assault. Am J Community Psychol. 2017 Mar;59(1-2):65-79. [ Links ]

Received: March 13, 2017; Accepted: November 10, 2017

texto en

texto en