Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.28 no.1 Brasília mar. 2019 Epub 24-Jan-2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742019000100002

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of the implantation of the Notifiable Diseases Information System in Pernambuco state, Brazil, 2014*

1Secretaria de Saúde de Jaboatão dos Guararapes, Núcleo de Apoio à Saúde da Família, Jaboatão dos Guararapes, PE, Brasil

2Grupo de Estudos de Avaliação em Saúde, Instituto de Medicina Integral Prof. Fernando Figueira, Recife, PE, Brasil

3Secretaria Estadual de Saúde de Pernambuco, Diretoria de Vigilância em Saúde, Recife, PE, Brasil

Objective:

to evaluate the implantation of the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) in Pernambuco, Brasil, 2014.

Methods:

This was an evaluation study based on primary data (interviews) and secondary data (SINAN documents/data) provided by the State Health Department and its Regional Divisions in order to estimate the degree of SINAN implantation, comparing structure and process indicators with results achieved.

Results:

SINAN was found to be partially implemented at central level (77.2%); and at regional level (61.2%), ranging from 54.7 to 71.6%; the following components had been implemented: reporting/investigation (90.0%) and processing (84.1%); analysis/divulgation had been partially implemented (61.6%); while monitoring (53.4%) and management (56.8%) were incipient; there was a lack of planning and published information bulletins; 46.9% of municipalities closed compulsory reporting on time; 68.7% sent batches regularly, 3.0% of tuberculosis cases were duplicated.

Conclusion:

SINAN was found to be partially implemented in Pernambuco due to shortcomings in monitoring and management, with negative influences on system results; its strengths related to reporting, investigation and data processing.

Keywords: Health Evaluation; Information Systems; Disease Notification; Epidemiological Monitoring

Introduction

The Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) was created in the 1990s1 and has been evaluated according to attributes of quality, coverage, completeness of form filling and reliability, based on secondary data on specific diseases.2,3 Disease control institutions recommend that surveillance systems evaluations be focused on specific diseases,4 in order to ensure the efficient and effective monitoring of important Public Health problems.5,6

When evaluations have specific dimensions their usefulness is restricted,7 with gaps remaining in knowledge about the complete process of information production. There is a scarcity of evaluation research addressing the totality of health surveillance information systems, such as studies that have identified weaknesses in organizational settings and in the data collection, processing, transmission and dissemination stages,8,9 so as to contribute to the development of strategies favouring better information coverage, regularity and quality.9,10

Accurate and timely information is needed in order for epidemiological surveillance to be effective.1,11 The globalized world, characterized by individual mobility and the constant flow of groups of people between countries and regions, requires structured services capable of providing quick responses to Public Health emergencies and monitoring national and international agreements and commitments.11,12 The shortage of SINAN evaluation studies hinders identification of flaws in information generation, causing repercussions for the decision-making process.

The diversity of methodological approaches, in turn, enables more in-depth studies as to the operational adequacy of systems, ranging from data collection to information being publicized, whereby studies that encompass the entire information production process are useful.9 The objective of this study was to evaluate SINAN implantation in the state of Pernambuco in 2014.

Methods

This is an evaluation study using implantation analysis, with the purpose of examining the influence of variation in the degree of implantation of an intervention on the effects observed.13 The single-case study strategy was used,14 focused on the state of Pernambuco and its central and regional health levels.

The SINAN system is in operation in the twelve political/administrative regions of Pernambuco, corresponding to its regional health divisions which cover the state’s 185 municipalities. The purpose of the system is to collect, process, transmit and disseminate epidemiological data which are generated by health professionals as part of the service routine. Cases of compulsory notifiable diseases are registered on investigation forms which are sent to the municipal epidemiological surveillance service which is responsible for inputting them on SINAN, taking control measures and closing investigations based on case evolution.1

Our evaluation was carried out in four stages:

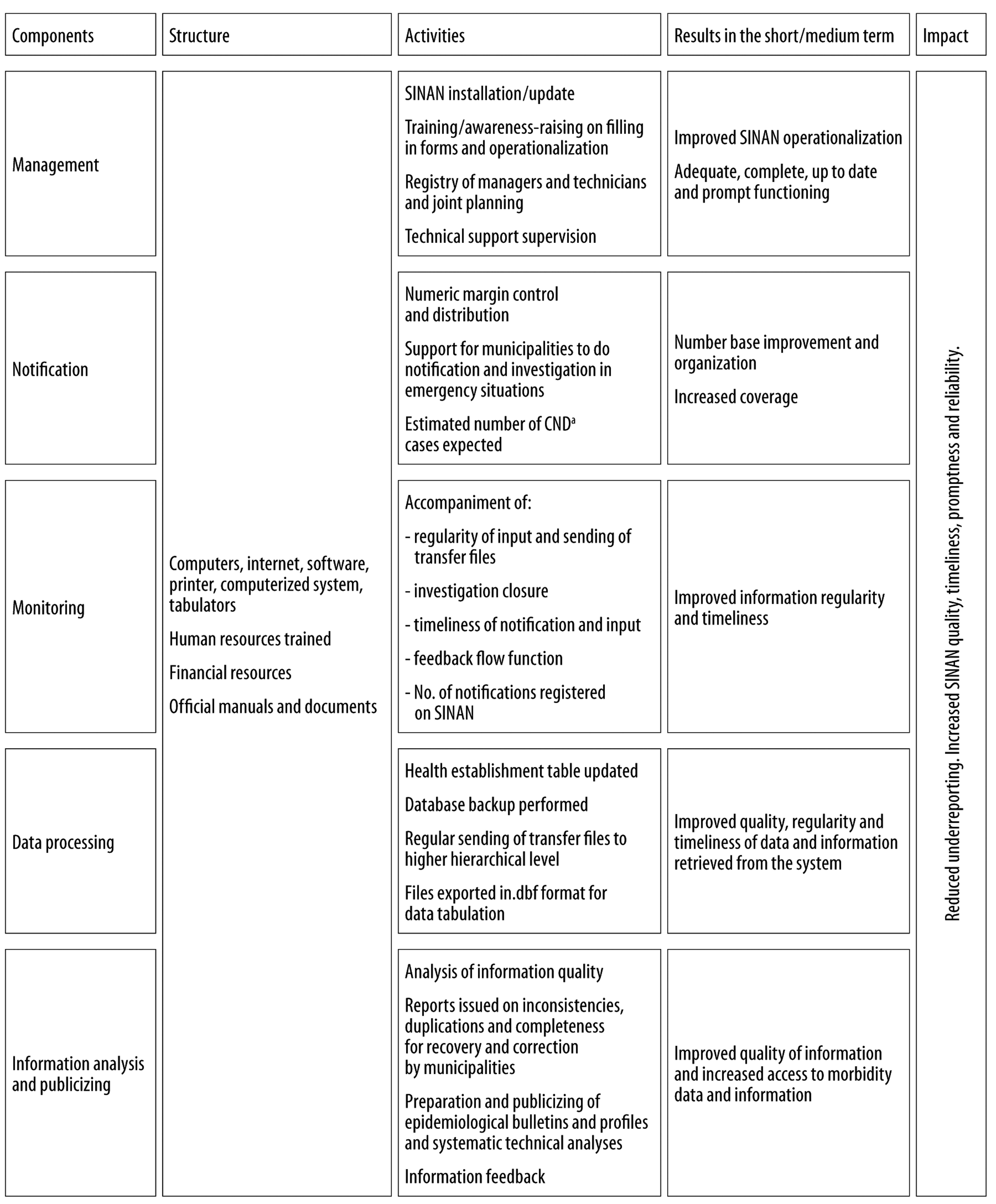

Stage 1 - Preparation of the logic model for SINAN

In order to detail the intervention we evaluated, we designed the logic model for SINAN at state level (Figure 1) based on the trinity of structure-process-result15 within the five technical components of an information system: management; notification and investigation; monitoring; data processing; information analysis and publicizing. The analysis was built based on the following normative documents: Normative Instruction SVS/MS No. 2/2005; manuals (SINAN Net, norms and routines 2007; SINAN Online Operation Manual, SINAN Reports); and ministerial ordinances (SVS/MS No. 201/2010, issued by the MoH Health Surveillance Secretariat; and GM/MS No. 1.271/2014, issued by the Health Minister’s Office).

a) CND: compulsory notifiable disease.

Figure 1 - Logic Model for state-level Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN), Pernambuco, 2014

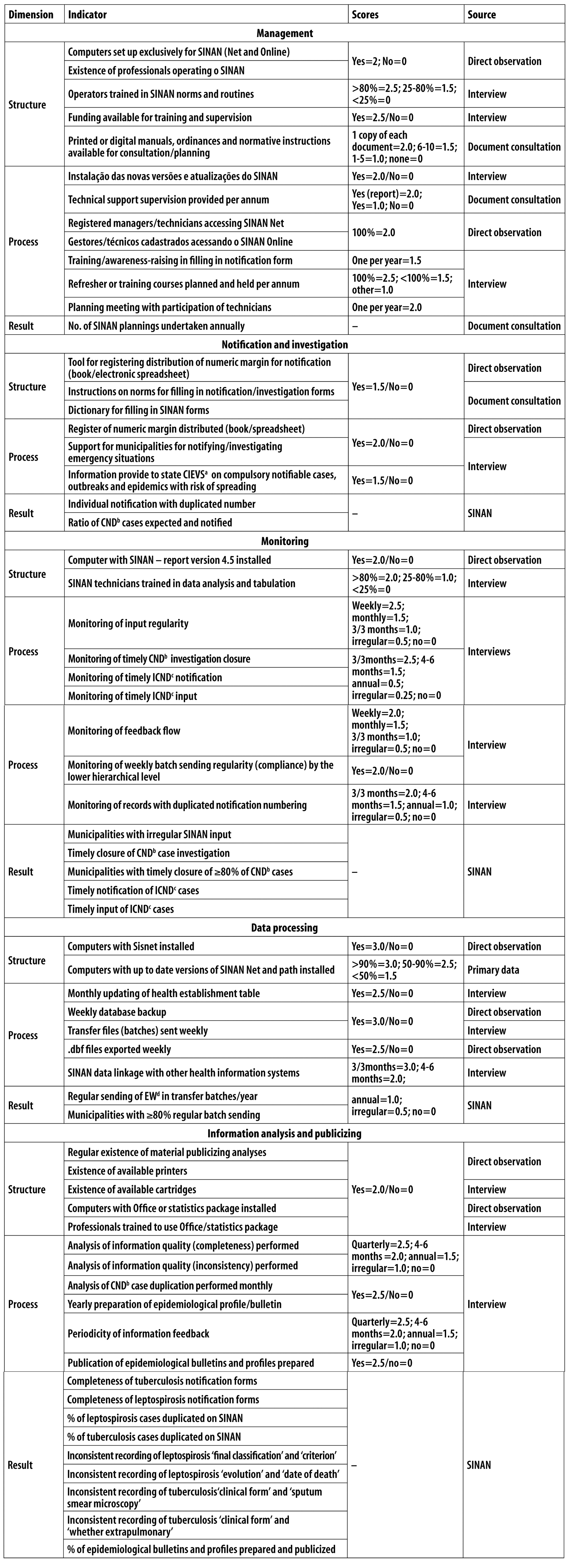

Stage 2 - Building of the indicator and judgement matrix

The indicator matrix and judgement criteria were prepared based on the state-level SINAN logic model. All the indicators were submitted to system technical staff and managers in order to validate the construct and the criteria. An adapted version of the nominal group technique was used in two meetings with the participants, to whom these documents had been sent previously (Figure 2). When selecting the indicators we considered content validity, relevance, availability, ease of obtaining, calculation simplicity and timeliness, dividing the scores pre-established for the components between them. When defining the judgement criteria, we used the parameters set out in the legal instruments and/or scientific studies and if there were no parameters we created them in accordance with the service routine.

a) CIEVS: Health Surveillance Strategic Information Centre.

b) CND: compulsory notifiable disease.

c) ICND: immediate compulsory notifiable disease.

d) EW: epidemiological week.

Note: Scores are not attributed to results, nor are they included in the degree of implantation.

Figure 2 - Indicator and judgement matrix by Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) compnents, Pernambuco, 2014

Figure 2 shows the matrix of the 65 indicators by component, with 17 in the ‘structure’ dimension, 28 in the ‘process’ dimension with the judgement criteria and 20 in the ‘result’ dimension, which was not considered in the definition of the degree of implantation. Based on the indicators selected, we created the data collection instrument according to the SINAN system components.

The primary data were collected in November and December 2014, by means of interviews in which a questionnaire with 13 open questions was administered with all 13 epidemiological surveillance managers and 13 technicians responsible for SINAN at the central level and at the 12 regional health divisions; during this period we also undertook non-participant direct observation of structural and procedural aspects. The secondary data were taken from the normative documents and also retrieved from the SINAN database for the reference year (2014), in March 2015, in order to analyze the results indicators.

Stage 3 - Classification of degree of implantation

In order to define the degree of implantation, we used structure and process indicators according to SINAN’s five technical components. The participants of the nominal group technique gave a score to each of the components according to its relevance in making the state-level SINAN operational: management (25 points); notification and investigation (10 points); monitoring (20 points); data processing (20 points); and information analysis and publicizing (25 points). Degree of implantation was calculated taking the sum of the scores obtained in relation to the maximum scores foreseen for dimension, component, regional health divisions and central health level. Degree of implantation at the regional level was obtained by the arithmetic mean of the scores found for each of the 12 regions, while degree of implantation for the state as a whole was obtained by the arithmetic mean of the regional and central level scores. Degree of implantation was classified as follows: implemented, when percentages varying between 80.0 and 100.0% were achieved; partially implemented, 60.0%-79.9%; incipient, 40.0-59.9%; and not implemented, below 40.0%. This classification was defined by the authors based on a prior evaluation study of an information system.9

Stage 4 - Analysis of the results and analysis of the influence of degree of implantation on the effects observed

For analysis of the results (effects), we considered the indicators contained in the SINAN indicators and judgement matrix (Figure 2). When classifying the degree of completeness of the tuberculosis and leptospirosis notification forms we used the model proposed by Malhão et al.16 The analysis of degree of implantation done in stage 3 was compared with the result indicators, using a deductive process based on the SINAN logic model to identify elements bringing influence to bear on result achievement.

In order to increase the robustness of the system implantation analysis, we triangulated information regarding the structure and process dimensions contained in the interviews with the non-participant direct observation at the 12 regional health divisions and at the central health level, as delineated in the single-case study of SINAN/Pernambuco. Triangulation was used as a strategy capable of adding rigour, amplitude and depth to the investigation.17

The study project was approved on November 21st 2014 by the Prof. Fernando Figueira Institute of Integral Medicine Human Research Ethics Committee - Opinion No. 4488/14; Certificate of Submission for Ethical Consideration (CAAE) No. 488214.400005201. All the participants agreed to take part in the study and signed the Free and Informed Consent form.

Results

SINAN was found to be partially implemented in Pernambuco (69.2%), at the central level (77.2%) and the regional level (61.2%). The system was incipient in seven of the twelve regional health divisions. Implantation of the structure dimension was better than that of the process dimension at the central and regional level, with the exception of the notification and investigation component (Table 1).

Table 1 - Degree of implantation (%) of the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) at the central, regional and state levels, by components and dimension, Pernambuco, 2014

| Component | Health regions and degree of implantation | Regional Level | Central Level | State | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | ||||

| Management | 46.0 | 48.0 | 40.0 | 48.0 | 54.0 | 46.0 | 58.0 | 54.0 | 50.0 | 48.0 | 58.0 | 46.0 | 49.7 | 64.0 | 56.8 |

| Structure | 63.6 | 50.0 | 72.7 | 68.2 | 72.7 | 72.7 | 77.3 | 63.3 | 50.0 | 45.5 | 54.5 | 63.6 | 62.9 | 68.2 | 65.5 |

| Process | 32.1 | 46.4 | 14.3 | 32.1 | 39.3 | 25.0 | 42.9 | 46.4 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 60.7 | 32.1 | 39.3 | 60.7 | 50.0 |

| Notification and investigation | 70.0 | 70.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 85.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 85.0 | 70.0 | 100.0 | 70.0 | 80.0 | 100.0 | 90.0 |

| Structure | 33.3 | 33.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 100.0 | 33.3 | 100.0 | 33.3 | 61.1 | 100.0 | 80.6 |

| Process | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 72.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 72.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 100.0 | 97.7 |

| Monitoring | 33.8 | 57.5 | 32.5 | 38.8 | 47.5 | 38.8 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 55.0 | 26.3 | 55.0 | 47.5 | 44.4 | 62.5 | 53.4 |

| Structure | 75.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 | 70.8 | 75.0 | 72.9 |

| Process | 23.4 | 53.1 | 28.1 | 23.4 | 40.6 | 29.7 | 68.8 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 20.3 | 43.8 | 46.9 | 37.8 | 59.4 | 48.6 |

| Data processing | 85.0 | 75.0 | 72.5 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 70.0 | 85.0 | 70.0 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 80.6 | 87.5 | 84.1 |

| Structure | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Process | 78.6 | 64.3 | 60.7 | 78.6 | 78.6 | 78.6 | 57.1 | 78.6 | 57.1 | 78.6 | 78.6 | 78.6 | 72.3 | 82.1 | 77.2 |

| Information analysis and publicizing | 48.0 | 40.0 | 44.0 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 40.0 | 70.0 | 44.0 | 84.0 | 44.0 | 60.0 | 44.0 | 51.2 | 72.0 | 61.6 |

| Structure | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Process | 13.0 | - | 6.7 | 13.3 | 13.3 | - | 50.0 | 6.7 | 73.3 | 6.7 | 33.3 | 6.7 | 18.6 | 53.3 | 36.0 |

| SINAN | 56.6 | 58.1 | 57.8 | 64.0 | 63.9 | 56.0 | 67.6 | 56.6 | 68.8 | 54.7 | 71.6 | 58.5 | 61.2 | 77.2 | 69.2 |

With regard to the state as a whole, the notification and investigation (90.0%) and data processing (84.1%) components were implemented; however, management (56.8%) and monitoring (53.4%) were incipient, with 40.0-58.0% variation between the health regions for the former and 26.3-70.0% for the latter. The monitoring component was not implemented in six regions; information analysis and publicizing was partially implemented at state level (61.6%), varying from 40.0-84.0% between the regions (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the result indicators according to the SINAN components for the central and regional health levels. The management component indicator ‘number of SINAN plannings undertaken annually’ was inexistent for the state as a whole; and the notification and investigation component indicator ‘Regional consistency of notification volume’ was 28.7% implemented on both levels - regional and central -, varying from 24.1-36.9%. With regard to the monitoring component, the ‘timely closure of compulsory notifiable disease investigations’ (CND) indicator on the state level was 78.1%; while for the data processing component the ‘municipalities with ≥80% regular batch sending’ indicator showed considerable differences between the health regions, ranging from 0% to 100.0%. In relation to the information analysis and publicizing component, ‘completeness of tuberculosis notification forms’ reached a rate of 10.1 for the state as a whole, varying between 9.1 (good) and 12.4 (excellent) between the health regions, while ‘completeness of the leptospirosis notification forms’, reached a rate of 8.8 for the state as a whole, varying between 5.2 (poor) and 13.1 (excellent) between the health regions.

Table 2 - Result indicators for Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) components at the central, regional and state levels, Pernambuco, 2014

| Component/Indicator | Health Regions | Regional Level | Central Level | State | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | ||||

| Management | |||||||||||||||

| No. of SINAN plannings undertaken annually | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Notification and investigation | |||||||||||||||

| Individual notification with duplicated number | 3.9 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| Ratio of expected and notified CND a cases | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | - | - | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Regional consistency of notification volume | 36.9 | 24.1 | 24.2 | 30.5 | 25.0 | 24.2 | 32.1 | 33.2 | 28.3 | 29.4 | 31.5 | 24.7 | 28.7 | 28.7 | 28.7 |

| Monitoring | |||||||||||||||

| Municipalities with irregular input to SINAN | - | - | 4.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Timely closure of CND a investigations | 77.6 | 72.5 | 72.3 | 73.5 | 77.8 | 78.9 | 92.9 | 94.5 | 85.3 | 75.0 | 80.0 | 69.9 | 79.2 | 77.0 | 78.1 |

| Municipalities with timely closure of ≥80% CND a cases | 50.0 | 55.0 | 40.9 | 34.4 | 47.6 | 46.2 | 42.9 | 71.4 | 36.4 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 47.9 | 45.9 | 46.9 |

| Timely notification of ICND b cases | 12.4 | 24.4 | 15.9 | 30.7 | 8.3 | 24.2 | 16.7 | 26.5 | 43.8 | 21.4 | 37.5 | 15.2 | 23.1 | 13.6 | 18.3 |

| Timely input of ICND b cases | 20.7 | 48.8 | 31.7 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 39.4 | 54.2 | 18.4 | 43.8 | 64.3 | 37.5 | 38.0 | 41.4 | 23.6 | 32.5 |

| Data processing | |||||||||||||||

| Regular sending of EW c in transfer batches /year | 88.5 | 86.5 | 88.5 | 98.1 | 90.4 | 92.3 | 88.5 | 94.2 | 92.3 | 88.5 | 98.1 | 80.8 | 90.5 | 82.7 | 86.6 |

| Municipalities with ≥80% regular batch sending | 50.0 | 75.0 | 63.6 | 71.9 | 61.9 | 76.9 | - | 100.0 | 36.4 | 100.0 | 90.0 | 100.0 | 68.8 | 68.6 | 68.7 |

| Information analysis and publicizing | |||||||||||||||

| Completeness of tuberculosis notification forms | 12.4 | 11.0 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 9.1 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 10.1 |

| Completeness of leptospirosis notification forms | 7.5 | 9.7 | 9.4 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 10.6 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 8.8 |

| % of leptospirosis cases duplicated on SINAN | 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| % of tuberculosis cases duplicated on SINAN | 3.0 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 6.9 | 6.3 | - | - | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| Inconsistent recording of leptospirosis ‘final classification’ and ‘criterion’ | 1.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Inconsistent recording of leptospirosis ‘evolution’ and ‘date of death’ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Inconsistent recording of tuberculosis ‘clinical form’ and ‘spuum smear microscopy’ | 0.5 | - | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | - | - | - | - | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Inconsistent recording of tuberculosis ‘clinical form’ and ‘whether extrapulmonary’ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | - | - |

| % epidemiological bulletins and profiles prepared and publicized | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

a) CND: compulsory notifiable disease.

b) ICND: immediate compulsory notifiable disease.

c) EW: epidemiological week.

In Table 3, coherence was found between degree of implantation and results indicators. In the case of the notification and investigation component, which was found to be implemented (90.0%), the result for one of the three indicators, ‘regional consistency of notification volume’, was lower than expected (28.7%). With regard to the nine indicators of the analysis and publicizing component, which was identified as being partially implemented (61.6%), only one indicator, ‘proportion of epidemiological bulletins and profiles prepared and publicized’, had no score.

Table 3 - Degree of implantation of the state-level Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) by component and result indicators, Pernambuco, 2014

| Component | Degree of implantation (%) | Indicadores | Metas | Resultado |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management | 56.8 (incipient) | No of SINAN plannings undertaken annually | 1 | - |

| Notification and investigation | 90.0 (implemented) | Individual notification with duplicated number | <5% | 1.7 |

| Ratio of expected and notified CND a cases | 1 | 0.9 | ||

| Regional consistency of notification volume | >80% | 28.7 | ||

| Monitoring | 53.4 (incipient) | Municipalities with irregular input to SINAN | zero | 0.5 |

| Timely closure of CND a investigations | ≥80% | 78.1 | ||

| Municipalities with timely closure of ≥80% CND a cases | ≥50% | 46.9 | ||

| Timely notification of ICND b cases | 100% | 18.3 | ||

| Timely input of ICND b cases | 100% | 32.5 | ||

| Data processing | 84.1 (implemented) | Regular sending of EW c in transfer batches /year | ≥80% | 86.6 |

| Municipalities with ≥80% regular batch sending | ≥50% | 68.7 | ||

| Information analysis and publicizing | 61.6 (partially implemented) | Completeness of tuberculosis notification forms | >8.9 | 10.1 |

| Completeness of leptospirosis notification forms | >8.9 | 8.8 | ||

| % of leptospirosis cases duplicated on SINAN | ≤5% | 0.3 | ||

| % of tuberculosis cases duplicated o SINAN | ≤5% | 3.0 | ||

| Inconsistent recording of leptospirosis ‘final classification’ and ‘criterion’ | ≤5% | 1.0 | ||

| Inconsistent recording of leptospirosis ‘evolution’ and ‘date of death’ | ≤5% | - | ||

| Inconsistent recording of tuberculosis ‘clinical form’ and ‘sputum smear microscopy | ≤5% | 0.3 | ||

| Inconsistent recording of tuberculosis ‘clinical forma’ and ‘whether extrapulmonary’ | ≤5% | - | ||

| % of epidemiological bulletins and profiles prepared and publicized | ≥50% | - |

a) CND: compulsory notifiable disease.

b) ICND: immediate compulsory notifiable disease.

c) EW: epidemiological week.

Discussion

SINAN in Pernambuco was found to be partially implemented, with variations between health regions generally coherent with the low effects achieved. The system does not fully meet its objectives owing to organizational shortcomings, despite being in operation for more than 20 years18 and despite being an important information production tool.1,19

The routine activities undertaken by central level technicians to improve indicators of data completeness, duplication and inconsistency may conceal negative results in the health regions. In turn, the SINAN logic model and indicator and judgement matrix, which were validated by the state-level team without being appraised by specialists at other hierarchical levels, may have weaknesses in the study judgement criteria and may be subject to changes, given that the nominal group expresses the opinion of the participant without the inconvenience of interactions with multiple stakeholders. Moreover, the validity of the logic model is related to the quality of theoretical articulation and to the complexity of the interdependence between components. For this reason, the logic model can be applied to other places, with some adaptations; notwithstanding, the results cannot be extrapolated.14,17

Management and monitoring were found to be the critical components of the state SINAN, this being reflected in the inexistence of planning and insufficiency of timely notification, case closure and data input. However, health information systems should provide reliable data identifying relevant events and enabling rapid responses to Public Health problems. In view of the flow of people between countries with a multiplicity of diseases, accurate information reinforces the importance of these systems for epidemiological surveillance.18-20

In our case study, the SINAN management component in Pernambuco as a whole and in all its health regions was found to be incipient, with negative repercussions on system coordination. This may possibly have been observed because, although in Brazil information systems are coordinated at the three management levels (national, state and municipal), there is no full joint accountability between the different levels of the Brazilian federation.1 This has repercussions on the quality of data produced, especially at local level. In Pernambuco, the evaluation of SINAN structure was better than the evaluation of SINAN process, despite the need for good quality internet access. These structural aspects of some of the health regions studied are similar to the finding of a study conducted in the state of São Paulo on the Mortality Information System (SIM), whereby there was greater availability of computers and staff and better access to fast internet in municipalities with larger populations.21

Well-structured health information systems are essential for accompanying the progress of national and local strategic indicators;22 including those agreed to in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG),23 in particular SDG 3 in relation to diverse communicable diseases, including neglected ones. On the international level, the lessons learned from the results of the Millennium Development Goals relating to mortality and morbidity show the need for developed information systems with compete and accurate information. The health challenges of the forthcoming decade cannot be addressed without effective information system management.20,22-24

It was expected, given the length of time SINAN has been in existence, that the work process would be adequate, but this was not what our study found. Inconsistencies in the attributions of each management level9 can be related to the historical centralizing conception of systems the function of which, at the local level, has been restricted to data collection.25 State management takes on the responsibilities of municipalities when they do not undertake them. The same occurs with the health regions,9 which perhaps explains incoherencies revealed in our study such as the incipient degree of implantation in the majority of these regions, which diverges from the good quality of the indicators of effects relating to the information analysis and publicizing component.

Shortcomings in completeness owing to poor filling in of forms by health service workers were not minimized by information being recovered at the state level. If monitoring and recovery of incomplete or inconsistent variables were a routine hospital or municipal epidemiological surveillance activity, this would enable greater knowledge of disease magnitude and profile, thus favouring planning and execution of strategic actions.11,26

Despite monitoring being a relevant attribute of the state and health region levels, the effect indicators relating to timeliness were lower than expected. This fact arose from irregular periodicity and reflected on the promptness of the surveillance system and on the taking of measures for the prevention and control of health events.5,26-28 These monitoring indicator results may indicate low acceptance of the surveillance system by the health workers involved. Usually, acceptance is greater when the usefulness of the information produced is recognized. To achieve this, health workers who produce the information need system managers to provide awareness-raising and training.19,29

The degree of data processing implantation was coherent with the result indicators, probably because this is an essential routine for the system and which has been improved in the face of criticism as to coherence between variables, correction of mistakes and enhanced quality of information.1,27-30 Notwithstanding, the state-level SINAN system should not be restricted only to these activities.

SINAN in Pernambuco was found to be partially implemented. This had repercussions on the results achieved and presented in our study. The management and monitoring components were the main obstacles to full system implantation, especially the aspects relating to work process, whilst its strengths related to notification and investigation and data processing. In order for SINAN to fully meet its objectives, services need to be reorganized and there needs to be greater mobilization of resources and greater investment in the qualification of surveillance and disease information systems involving epidemiological rationality, associated with new evaluation research to deepen knowledge regarding the weaknesses of health information systems.

REFERENCES

1. Caetano R. Sistema de informação de agravos de notificação (Sinan). In: Ministério da Saúde (BR). Organização Pan-Americana de Saúde. Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. A Experiência brasileira em sistemas de informação em saúde [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009 [citado 2016 mar 10]. p.41-64. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/experiencia_brasileira_sistemas_saude_volume2.pdf [ Links ]

2. Lima CRA, Schramm JMA, Coeli CM, Silva MEM. Revisão das dimensões de qualidade dos dados e métodos aplicados na avaliação dos sistemas de informação em saúde. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009 out;25(10):2095-109. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2009001000002 [ Links ]

3. Delziovo CR, Bolsoni CC, Lindner SR, Coelho EBS. Qualidade dos registros de violência sexual contra a mulher no sistema de informação de agravos de notificação (Sinan) em Santa Catarina, 2008-2013. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2018;27(1):e20171493. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742018000100003 [ Links ]

4. German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, Milstein RL, Pertowski CA, Waller MN, et al. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001 Jul;50(RR13):1-35. [ Links ]

5. Barbosa JK, Barrado JCS, Zara ALSA, Siqueira Júnior JB. Avaliação da qualidade dos dados, valor preditivo positivo, oportunidade e representatividade do sistema de vigilância epidemiológica da dengue no Brasil, 2005 a 2009. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2015 jan-mar;24(1):49-58. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742015000100006 [ Links ]

6. Cantarino L, Merchan-Hamann E. Influenza in Brazil: surveillance pathways. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016 Jan;10(1):13-23. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7135 [ Links ]

7. Patton MQ. The challenges of making evaluation usefull. Ensaio: Aval Pol Públ Educ. 2005 jan-mar;46(13):67-78. doi: 10.1590/S0104-40362005000100005 [ Links ]

8. Vasconcelos CS, Frias PG. Evaluation of the Influenza-like syndrome surveillance: case studies in sentinel unit. Saúde Debate. 2017 mar;41(n. spe):259-74. doi: 10.1590/0103-11042017s19 [ Links ]

9. Pereira CCB, Vidal SA, Carvalho PI, Frias PG. Avaliação da implantação do sistema de informações sobre nascidos vivos em Pernambuco. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2013 jan-mar;13(1):39-49. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292013000100005 [ Links ]

10. Melo CF, Leite MJVF, Carvalho JBLF, Silva ER, Aquino GML, Macedo CP, et al. As gestões municipais e o uso das informações no pacto pela saúde no estado do Rio Grande do Norte. HOLOS. 2012;28(6):220-36. [ Links ]

11. Cerroni MP, Carmo EH. Magnitude das doenças de notificação compulsória e avaliação dos indicadores de vigilância epidemiológica em municípios da linha de fronteira do Brasil, 2007 a 2009. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2015 out-dez;24(4):617-28. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742015000400004 [ Links ]

12. Anema A, Druyts E, Hollmeyer HG, Hardiman MC, Wilson K. Descriptive review and evaluation of the functioning of the International Health Regulations (IHR) Annex 2. Global Health. 2012 Jan;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-1 [ Links ]

13. Champagne F, Brousselle A, Hartz ZMA, Contandriopoulos AP, Denis JL. A análise de implantação. In: Brousselle A, Champagne F, Contandriopoulos AP, Hartz ZMA. Avaliação conceitos e métodos. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2011. p. 217-38. [ Links ]

14. Yin RK. Estudo de caso: planejamento e métodos. 5. ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman; 2015. [ Links ]

15. Donabedian A. The definition of quality: a conceptual exploration. In: Arbor A. The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Michigan: Health Administration Press; 1980. p. 3-31. (Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring , v. 1). [ Links ]

16. Malhão TA, Oliveira GP, Codennoti SB, Moherdaui F. Avaliação da completitude do sistema de informação de agravos de notificação da tuberculose, Brasil, 2001-2006. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2010 jul-set;19(3):245-256. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742010000300007 [ Links ]

17. Denzin NK, Lincoln Y. The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln Y. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2000. p. 1-28. [ Links ]

18. Zambrini DAB. Lecciones desatendidas entorno a la epidemia de dengue en Argentina, 2009. Rev Saúde Pública. 2011 abr;45(2):428-31. [ Links ]

19. Laguardia J, Domingues CMA, Carvalho C, Lauerman CR, Macário E, Glatt R. Sistema de informação de agravos de notificação (Sinan): desafios no desenvolvimento de um sistema de informação em saúde. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2004 set;13(3):135-47. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742004000300002 [ Links ]

20. Figueira GCN, Carvalhanas TRMP, Okai MIG, Yu ALF, Liphaus BL. Avaliação do sistema de vigilância das meningites no município de São Paulo, com ênfase para doença meningocócica. Bol Epidemiol Paul. 2012 jan;9(97):5-25. [ Links ]

21. Minto CM, Alencar GP, Almeida MF, Silva ZP. Descrição das características do Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade nos municípios do estado de São Paulo, 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2017 out-dez;26(4):869-80. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742017000400017 [ Links ]

22. AbouZahr C, Savigny D, Mikkelsen L, Setel PW, Lozano R, Nichols E, et al. Civil registration and vital statistics: progress in the data revolution for counting and accountability. Lancet. 2015 Oct;386(10001):1395-406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60171-4 [ Links ]

23. Organizações das Nações Unidas Brasil. Documento temático. Objetivos de desenvolvimento sustentável. 1.2.3.5.9.14 [Internet]. Brasília: Organizações das Nações Unidas; 2017 [citado 2018 out 8]. 103 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.br.undp.org/content/brazil/pt/home/library/ods/documentos-tematicos--ods-1-2-3-5-9-14.html [ Links ]

24. AbouZahr C, Savigny D, Mikkelsen L, Setel PW, Lozano R, Lopez AD. Towards universal civil registration and vital statistics systems: the time is now. Lancet. 2015 Oct;386(10001):1407-18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60170-2 [ Links ]

25. Vidor AC, Fisher PD, Bordin R. Utilização dos sistemas de informação em saúde em municípios gaúchos de pequeno porte. Rev Saúde Pública. 2011 feb;45(1):24-30. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102011000100003 [ Links ]

26. Abath MB, Lima MLLT, Lima PS, Silva MCM, Lima MLC. Avaliação da completitude, da consistência, e duplicidade de registros de violências do Sinan em Recife, Pernambuco, 2009-2012. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2014 jan-mar;23(1):131-42. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742014000100013 [ Links ]

27. Paula Júnior FJ, Matta ASD, Jesus R, Guimarães RP, Souza LRO, Brant JL. Sistema gerenciador de ambiente laboratorial - GAL: avaliação de uma ferramenta para a vigilância sentinela de síndrome gripal, Brasil, 2011-2012. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2017 abr-jun;26(2):339-48. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742017000200011 [ Links ]

28. Braz RM, Tauil PL, Santelli ACFS, Fontes CJF. Avaliação da completude e da oportunidade das notificações de malária na Amazônia Brasileira, 2003-2012. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2016 jan-mar;25(1):21-32. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742016000100003 [ Links ]

29. Santos KC, Siqueira Júnior JB, Zara ALSA, Barbosa JR, Oliveira ESF. Avaliação dos atributos de aceitabilidade e estabilidade do sistema de vigilância da dengue no estado de Goiás, 2011. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2014 abr-jun;23(2):249-58. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742014000200006 [ Links ]

30. Correia LOS, Padilha BM, Vasconcelos SML. Métodos para avaliar a completitude dos dados dos sistemas de informação em saúde do Brasil: uma revisão sistemática. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2014 nov;19(11):4467-78. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320141911.02822013 [ Links ]

*Article derived from the Master’s Degree dissertation entitled ‘Evaluation of the implantation of the Notifiable Diseases Information System in Pernambuco’, submitted by Daniely Aleixo Barbosa Maia to the Professional Master’s Degree Course, Health Evaluation Postgraduate Programme, Prof. Fernando Figueira Institute of Integral Medicine, on December 23rd 2015.

Received: July 06, 2018; Accepted: October 22, 2018

texto em

texto em