Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versión impresa ISSN 1679-4974versión On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.28 no.2 Brasília jun. 2019 Epub 22-Ago-2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742019000200022

NARRATIVE REVIEW

Expansion of Zika virus circulation from Africa to the Americas, 1947-2018: a literature review*

1Universidade Federal da Bahia, Hospital Universitário Professor Edgard Santos, Salvador, BA, Brasil

2Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Institut für Virologie, Berlim, Alemanha

Objective:

to describe the temporal and geographical expansion of Zika virus (ZIKV) circulation in countries and territories, from the time it was first isolated until 2018.

Methods:

This was a non-systematic literature review covering the period from 1947 to 2018 using the MEDLINE database and World Health Organization estimates.

Results:

Since its isolation in 1947, ZIKV circulation spread through Africa, Asia and the Pacific before reaching the Americas in 2013, causing serious clinical manifestations; the highest seroprevalence rates were recorded in Yap (74%) and in Brazil (63%); genetic mutations, absence of immunity and high vector susceptibility may have influenced ZIKV transmissibility and help to explain the magnitude of its expansion.

Conclusion:

The spread of ZIKV circulation in the Americas was the most extensive recorded thus far, possibly as a result of population and geographical characteristics of the sites where the virus circulated.

Keywords: Zika Virus, Flavivirus; Epidemiology; Epidemics; Congenital Abnormalities; Review Literature as Topic

Introduction

Following its discovery in 1947, Zika virus (ZIKV) was responsible for sporadic cases of mild infections that were not cause for great concern and were limited to the African and Asian continents.1 This scenario changed with effect from 2007, when the virus began to be considered a pathogen capable of causing large epidemics after having produced two large-scale outbreaks in the Pacific Islands2-4 and in French Polynesia.4-6 ZIKV circulation continued to expand (Figure 1A). Within a short time, the virus was considered to be a Public Health concern associated with a large number of microcephaly cases that occurred in Brazil.7,8

Notes:

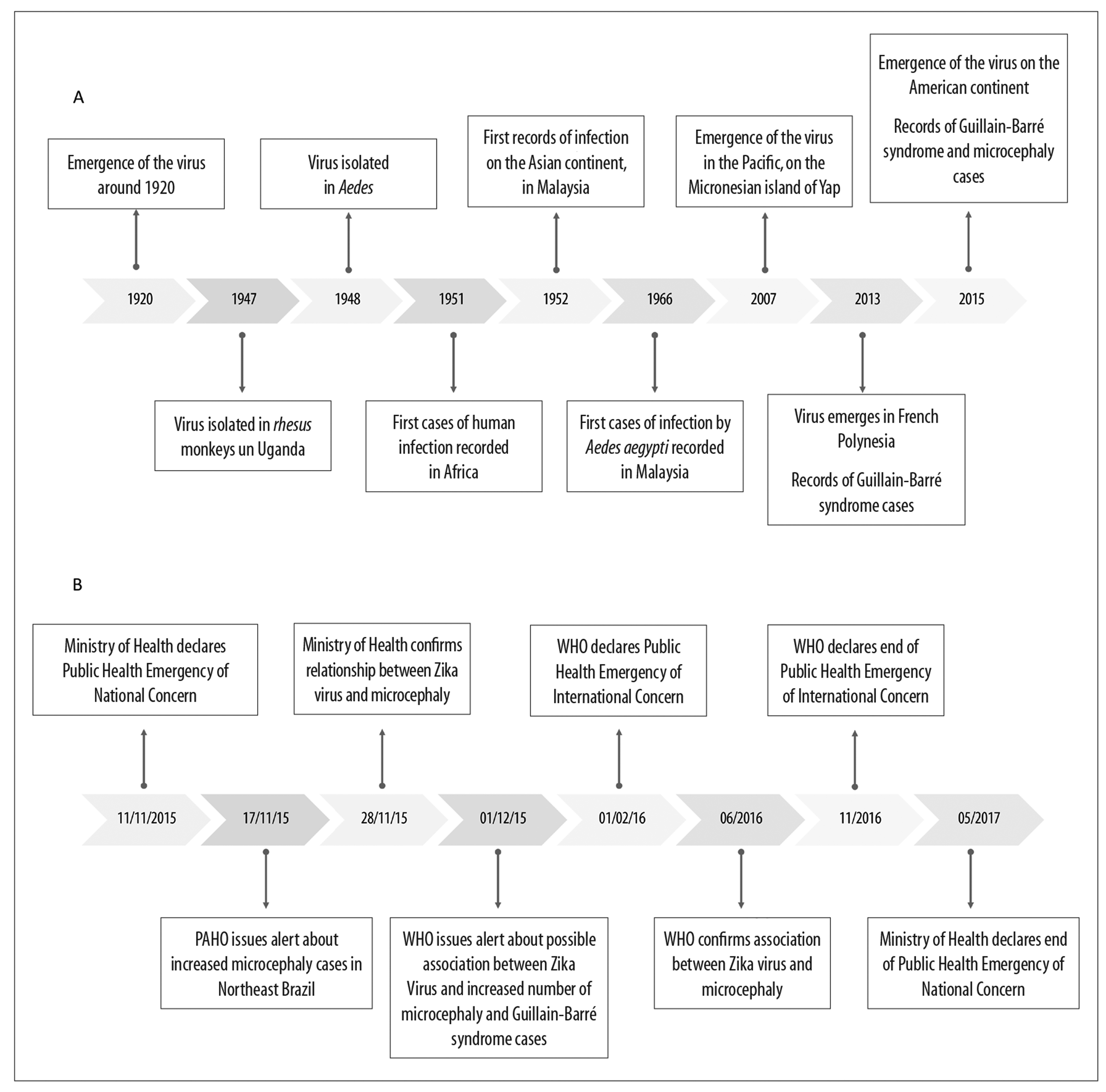

A) Timeline of Zika virus circulation expansion up until 2015.

B) Measures adopted by health authorities (Brazilian Ministry of Health, Pan American Health Organization [PAHO] and World Health Organization [WHO]) in the face of the increased number of microcephaly Guillain-Barré syndrome cases in Brazil.

Figure 1 - Timeline of Zika virus circulation expansion and measures adopted by health authorities

Concern as to the severity of the consequences of infection led the Ministry of Health to declare a state of Public Health Emergency of National Concern on November 11th 2015.9 Following this declaration, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an alert about the increased number of microcephaly cases in Brazil’s Northeast region.10 Just days afterwards, on November 28th 2015, despite there being little evidence, the Ministry of Health confirmed the link between ZIKV and the microcephaly outbreak.11 On December 1st 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) and PAHO issued an alert suggesting possible association between ZIKV and the increase in cases of congenital syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome.12 On February 1st 2016, WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.13 The agility with which health authorities and researchers acted enabled rapid proof of the causal relationship between ZIKV infection and the occurrence of microcephaly and other central nervous system alterations. This position was endorsed by WHO at a meeting of the Emergency Committee held in June 201614 (Figure 1B).

The potential of the virus to give rise to a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations was confirmed, ranging from non-specific symptoms, easily confused with other virus diseases, to neurological manifestations and congenital malformations.7,8,15-19 By the end of 2016, 2,366 Zika virus-associated congenital abnormalities had been confirmed in Brazil.20 The emergence of ZIKV in the Americas and the potential for its circulation to expand require better comprehension of its epidemiological profile, in order to facilitate understanding of the changes in infection detected over time.

The objective of this literature review was to describe the temporal and geographic expansion of KIKV circulation in countries and territories, from the time it was isolated up until 2018.

Methods

This is a narrative review of ZIKV circulation expansion over the years in countries and territories on diverse continents. We searched the MEDLINE database (via PubMed), using the following keywords retrieved from the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) virtual library: ‘zika’, ‘zika virus’, ‘flavivirus’ and ‘arbovirus’. Eligible articles were those that provided microbiological evidence of ZIKV infection in humans and non-humans published between 1947 and 2018, in any region of the world, and which contained complete information on how the study was conducted: period, place, sample, type of test used for diagnosis and test result. We excluded articles that did not present positive laboratory test results for the virus in humans or where virus isolation in non-humans was not conducted. No restriction was made as to language or whether the publication was free of charge or not.

We also used estimates, available on the official website of the PAHO-WHO, of confirmed Zika cases or confirmed cases of Zika infection-associated congenital syndrome, occurring in countries or territories in the Americas up until January 2018.21 In order to demonstrate the magnitude of infection in different places, ZIKA infection seroprevalence in the samples examined was calculated as follows: firstly we totaled the positive test results and then divided the total number of tests by the total number of samples in each study.

Global expansion of ZIKV circulation

1940s and 1950s

ZIKV is believed to have emerged in around 1920,1 although it was only isolated in 1947 in a study on yellow feber in Rhesus monkeys conducted by researchers from the Virus Research Institute.22 The term ‘Zika’ was borrowed from the name of the Zika forest, in Entebbe, Uganda, where the Institute was based. Despite the study mentioned above being focused on yellow feber and dengue, researchers found evidence of Zika virus being a new pathogen.22

In 1948, less than a year after its discovery, ZIKV was isolated in the Aedes (Stegomyia) africanus vector,22-24 even though at that time it was not known that it was a ZIKV vector.

ZIKV spread following its original lineage, referred to as African lineage Zika, and expanded over part of the African continent.1 In West Africa it was introduced twice, at different times, and gave origin to two African lineages.14

The first human ZIKV infections were recorded in 1952, on the African continent, and were confirmed by its presence in serum of ZIKA neutralizing antibodies.25,26 At that time there was no other way of demonstrating ZIKV infection, since test results could be biased because of a possible immune response to yellow feber vaccination.24 During the 1950s, studies identified the presence of these antibodies in people living in North Africa,27 West Africa,25,28 East Africa22,26,29,30 and Central Africa,31 as well as in South Asia32 and Southeast Asia27,32-34 (Figure 2 and Figure 3A). The highest seroprevalence rates were recorded in Malaysia and the Philippines: 50% and 36%, respectively (Table 1).

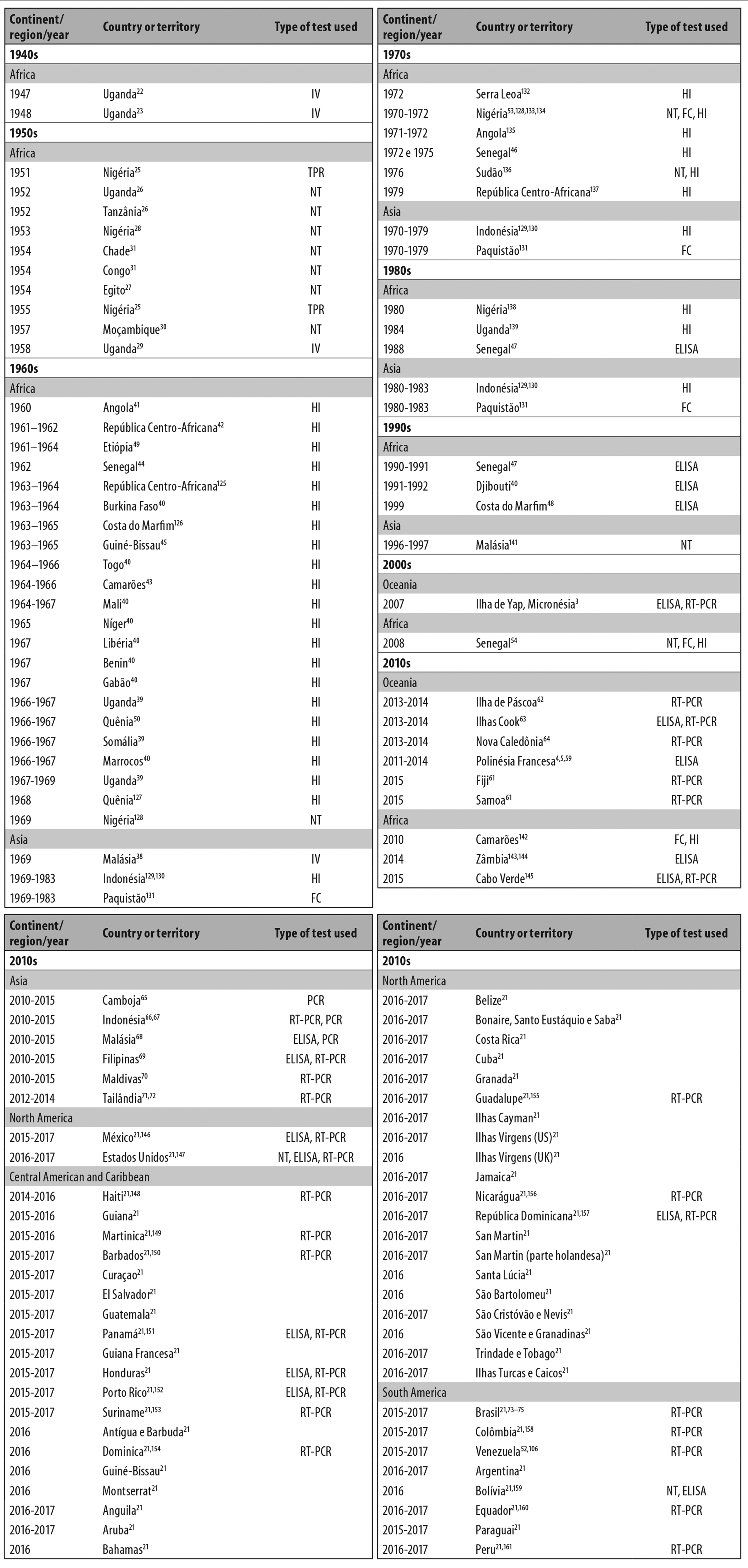

Legend:

NT: virus neutralization test to detect antibodies.

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

CF: complement fixation test.

HI: hemagglutination inhibition test.

IMT: intracerebrally inoculated mice test.

VI: virus isolation.

PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Figure 2 - Countries or territories recording Zika virus circulation between 1947 and 2018, listed by continent and decade of occurrence

Notes:

A) Countries or territories registering Zika virus circulation by the 1950s.

B) Countries or territories registering Zika virus circulation during the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

C) Countries or territories registering Zika virus circulation in the 2000s; the circle indicates the Pacific Islands.

D) All countries recording presence of Zika virus between 2010 and January 2018.

Figure 3 - Geographic and temporal expansion of Zika virus

Table 1 - Zika virus seroprevalence in humans by affected country and period of infection, 1947-2016

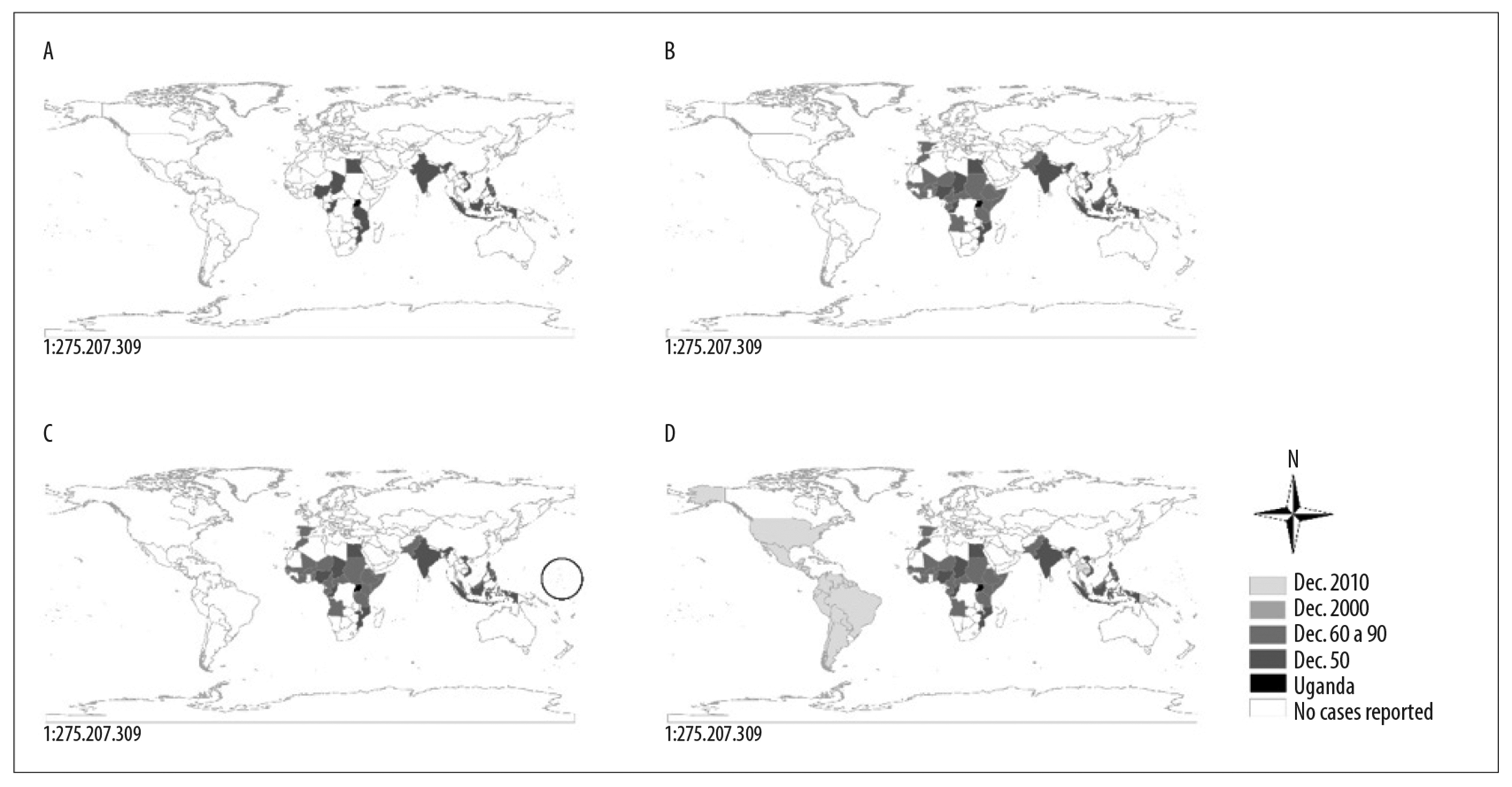

| Period | Country/reference | Type of test used | No. of cases | Total | Seroprevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947-1984a | Uganda23,26,39,127,139 | IMT, NT, HI | 56 | 798 | 7 |

| 1947-1952 | Tanzânia26 | IMT | 6 | 36 | 17 |

| 1951-1975b | Nigéria25,28,40,53,128,132,138 | NT,IMT,HI | 1,090 | 3,018 | 36 |

| 1952 | Índia27 | NT | 33 | 196 | 17 |

| 1953 | Filipinas34 | NT | 19 | 53 | 36 |

| 1953, 1954 | Malásia27,33 | NT | 90 | 179 | 50 |

| 1954 | Tailândia33 | NT | 8 | 50 | 16 |

| 1954 | Vietnã33 | NT | 2 | 50 | 4 |

| 1954 | Egito27 | NT | 1 | 180 | 1 |

| 1957 | Moçambique30 | NT | 10 | 149 | 7 |

| 1960-1972c | Angola41,135 | HI | 202 | 5,082 | 4 |

| 1961-1979d | República Centro-Africana42,125 | HI | 186 | 1,177 | 16 |

| 1961-1964 | Etiópia49 | HI | 48 | 1,316 | 4 |

| 1962-1990e | Senegal44,46,47 | HI, ELISA | 203 | 1,292 | 16 |

| 1963,1964 | Burkina Faso40 | HI | 1,005 | 1,896 | 53 |

| 1963-1999f | Costa do Marfim48,126 | HI, ELISA | 393 | 906 | 43 |

| 1964,1965 | Guiné-Bissau45 | HI | 122 | 1,054 | 12 |

| 1964-1966 | Togo40 | HI | 401 | 1,294 | 31 |

| 1964-2010g | Camarões43,142 | HI, CF | 626 | 3,714 | 17 |

| 1964-1967 | Mali40 | HI | 1,232 | 2,369 | 52 |

| 1965 | Níger40 | HI | 55 | 308 | 18 |

| 1966 | Somália39 | HI | 3 | 242 | 1 |

| 1966-1968 | Quênia50,127 | HI | 509 | 3,134 | 16 |

| 1967 | Benin40 | HI | 108 | 244 | 44 |

| 1967 | Gabão40 | HI | 50 | 717 | 7 |

| 1972 | Serra Leoa132 | HI | 62 | 899 | 7 |

| 1983 | Paquistão131 | CF | 1 | 43 | 2 |

| 1983 | Indonésia129,130 | HI | 9 | 71 | 13 |

| 2007 | Ilha de Yap, Micronésia3 | ELISA | 414 | 557 | 74 |

| 2011-2013h | Polinésia Francesa59 | ELISA | 319 | 1,069 | 30 |

| 2014 | Zâmbia144 | ELISA | 217 | 3,625 | 6 |

| 2015-2016 | Brasil123 | ELISA, PRNT | 401 | 633 | 63 |

a) 1947-1952, 1966, 1967, 1984.

b) 1951-1952, 1955, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1969-1971, 1971-1975, 1972.

c) 1960, 1971, 1972.

d) 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1979.

e) 1962, 1988, 1990.

f) 1963-1965, 1999.

g) 1964-1966, 2010.

h) 2011-2013, 2014.

Legend:

NT: virus neutralization test to detect antibodies.

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

CF: complement fixation test.

HI: hemagglutination inhibition test.

IMT: intracerebrally inoculated mice test.

PRNT: plaque reduction neutralization test.

Jaundice was found in the three human cases identified in 1954, indicating that the virus could also be viscerotropic.28 Another characteristics described was its affinity for nerve tissues, found in mice that developed neurological diseases after being infected.35Aedes aegypti was found to be a ZIKV vector in 1956.36

1960s to 1990s

The third ZIKV lineage, i.e. the Asian lineage, originated from a strain isolated in Malaysia in around 1966.37 It was here that the first Zika virus infection attributed to the Aedes aegypti vector was recorded.38 At that time, serological and virological evidence indicated that it was circulating in almost all of Africa, in its Northern,39,40 Central,40-43 Western40,44-48 and Eastern regions39,49,50 (Figure 2 and Figure 3B). The majority of the countries in these regions are located in latitudes where the climate is tropical and this is propitious for vector development. Joint circulation of yellow feber virus and Zika virus was found in a region of Ethiopia in 1968.49 Studies indicate that ZIKV antibodies can attenuate yellow feber virus infection but do not interfere with its transmission.51,52 In the decades in question, the highest seroprevalence rates were recorded in Burkina Faso (53%), Mali (52%) and Benin (44%).

2000s

For more than half a century, ZIKV remained confined to the African and Asian continents, before emerging in the Pacific Islands in the late 2000s.3 Between April and July 2007, the first large epidemic caused by the virus occurred in Yap, an island in Micronesia (Figure 2). Infection incidence was high in this outbreak at around 74% (95% confidence interval: 68-77).3 Despite affecting the majority of the population, only around 20% of total cases were symptomatic and reported mainly having exanthema, conjunctivitis and pain in their joints.2,3 The serum samples of the inhabitants of Yap were tested by means of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the virus neutralization test to detect antibodies (NT) and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Phylogenetic analyses showed that a strain of the Asian lineage of the virus was responsible for this outbreak.2

By the end of the 2000s, ZIKV had been isolated in Ae. Aegypti, Ae. africanus, Ae. apicoargenteus, Ae. luteocephalus, Ae. vitattus, Ae. Furcifer and Ae. Hensilii species vectors,36,38,48,51,53 whereby the latter was the most frequent species in the Yap outbreak.3 For a long time it was believed that the only form of Zika virus transmission was by the bite of mosquitoes of the Aedes genus.2,23,29,38,53 In 2008, however, two researchers were infected in Senegal and one of them transmitted ZIKV to his wife, possibly through sexual intercourse.54 Other studies have corroborated this hypothesis by indicating the possibility of this form of transmission.55,56

2010s

The 2010s were marked by important discoveries, such as the possibility of mother-to-child Zika virus transmission and clinical manifestations with unprecedented association with Zika virus infection, such as congenital abnormalities17,57,58 and Guillain-Barré syndrome.5,15,16

At that time the virus caused a new epidemic that affected a considerable part of the population of French Polynesia with effect from 2013, with approximately thirty thousand people infected5,6,59 and 42 patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome.15,16 That epidemic was the consequence of a new strain that appeared in the same year and was genetically related to the strains isolated in Yap in 2007 and in Cambodia in 2010.4,6 It is likely that its magnitude was the result of a population with low levels of immunity, high vector density59 and genetic mutations in which important amino acids were modified, increasing the capacity of Zika virus transmission by the Aedes aegypti vector.60

ZIKV continued to expand to other Pacific Ocean Islands4,5,59,61-64 and through Southeast Asia,65-72 until it was identified in the Americas in May 2015.73-75 Between 2015 and 2016, seroprevalence in Brazil was 63% (Table 1).

The timeline of Zika virus circulation expansion is shown in Figure 1A, while its geographic expansion is shown in Figure 3, highlighted by period to demonstrate its swiftness and extent.

The seroprevalence tests used in the various studies we consulted differ as to the method of laboratory diagnosis used and, therefore, have differing levels of sensitivity and specificity,76,77 thus compromising the comparability of the results of the different methods applied.

RT-PCR was used in 31 studies and was the most used test, followed by the hemagglutination inhibition test (HI) in 24 studies, ELISA in 17 studies, NT in 13 studies and the complement fixation test (CF) in 4 studies. Some studies used more than one diagnosis method. Cross-reactivity between ZIKV antibodies and those of other flaviviruses may also have compromised correct estimation of infection prevalence.78,79

ZIKV in the Americas

The first genetic studies of the strain causing the ZIKV epidemic on the American continent suggest that it originated from a unique Asian genotype lineage, introduced in Brazil between late 2013 and early 2014 and having come from French Polynesia.6,80-83 Four hypotheses have been raised regarding the introduction of the virus in Brazil. Initially it was thought that it had happened in 2014, during the FIFA World Cup,74 despite there being no Pacific countries among the participating soccer teams. A second possibility was that the virus was introduced during the Canoe Sprint World Championship, held in August 2014 in Rio de Janeiro, as there were teams from four Pacific countries with registered Zika cases: French Polynesia, New Caledonia, the Cook Islands and Easter Island.84 However, the hypothesis of the virus having entered Brazil via Rio de Janeiro does not help to explain why such a high number of cases were concentrated in the country’s Northeast region. The third hypothesis is that the virus was introduced one year earlier, between July and August 2013, during the Confederations Cup.81 According to the fourth and final hypothesis, the virus circulated in Oceania and Easter Island, spreading to Central America and the Caribbean before arriving in Brazil at the end of that year.85 The only ancestor of the cases studied was a strain from Haiti, indicating that ZIKV could have been introduced in Brazil by immigrants or Brazilian troops returning from that country. However, recent studies indicate that the virus followed a different route, namely from Brazil to Central America, entering via Honduras, between July and September 2014.86 Phylogeographic analysis has estimated that the virus arrived in Honduras from Brazil and later spread to Guatemala, Nicaragua and southern Mexico by early 2015. Another study corroborates the hypothesis that the introduction of ZIKV in South America occurred prior to its introduction in Central America, possibly in the first half of 2013.60

In Outober 2014, some municipalities of the Brazilian states of Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba and Maranhão reported suspected cases of a viral disease with presence of exanthema, mild feber, itching and painful joints, these being symptoms not in keeping with suspected cases of other exanthematous viral infections, such as measles and dengue. Before long a further six states reported exanthematous syndrome cases between October 2014 and March 2015.75 The intense and concomitant circulation of other flaviviruses, together with similar clinical presentation, low specificity of ELISA diagnostic tests for dengue76 as well as the fact of the presence of the pathogen in Brazil still being unknown, led to ZIKV not being indicated as the main suspect.

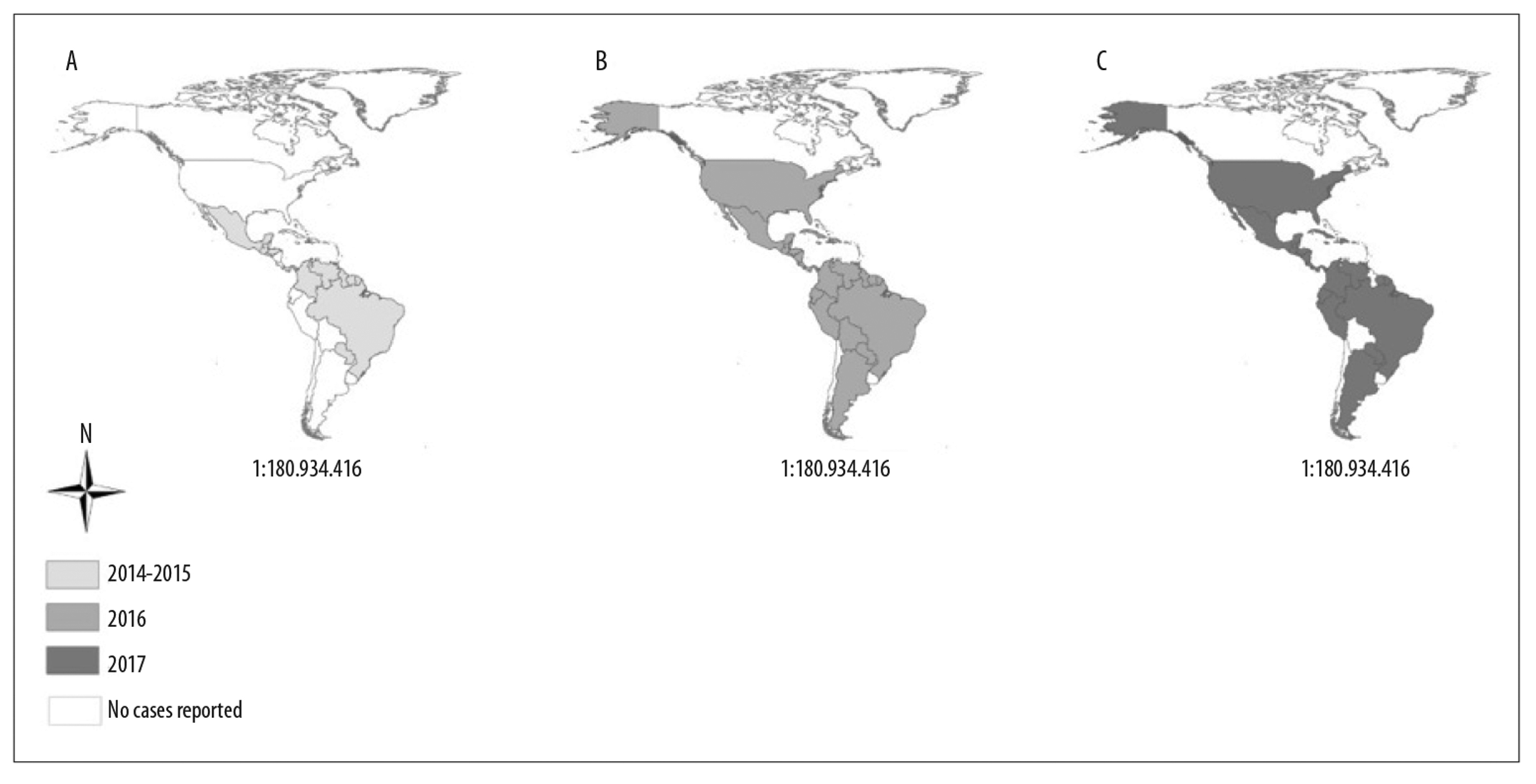

In March 2015, samples from the states of Rio Grande do Norte and Bahia had positive ZIKV results confirmed by RT-PCR.73,74 It spread well beyond Brazil’s borders. By late 2015, ten Central and Southern American countries had recorded autochthonous cases,87 and by the beginning of the next year this number had increased rapidly to 48 countries88,89 (Figure 2 and Figure 3D). Only Canada and Bermuda, both located in North America, and Chile and Uruguay, in South America, did not have autochthonous cases. Figure 4 shows the geographic and temporal spread of ZIKV in the Americas, from the first recorded case on the continent up until 2017.

Notes:

A) Countries or territories registering Zika virus circulation between 2014 and 2015.

B) Countries or territories registering Zika virus circulation in 2016.

C) Countries or territories registering Zika virus circulation in 2017.

Figure 4 - Geographic and temporal expansion of Zika virus in the Americas, 2015- 2017

Of all these countries, Brazil had the highest number of ZIKV infections, totaling 137,288 confirmed cases between 2015 and January 2018, followed by Puerto Rico and Mexico, with 40,562 and 11,805 confirmed cases, respectively.21 In 2016 the total number of cases reduced by more than 95% compared to the previous year and on November 18th 2016 WHO stopped considering the virus as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.90 In May 2017, the Brazilian Health Ministry also declared the end of the emergency.91

In the first semester of 2015, a change was noted in the pattern of the occurrence of Guillain-Barré syndrome in two states of Brazil’s Northeast region, namely Pernambuco and Bahia: in the former state the number of cases tripled compared to the previous year, with a peak in April, while Bahia recorded a peak in occurrence of the syndrome between June and July.92,93 In the same period, four patients undergoing solid organ transplantation were infected with ZIKV, diagnosed by RT-PCR between June 2015 and January 2016.94 In October of the same year, a change was detected in the epidemiological pattern of microcephaly occurrence, when Pernambuco state health authorities informed the Ministry of Health about a significant increase in the number of cases.95 In late November 2015, the Evandro Chagas Institute in the state of Pará, a body linked to the Health Ministry’s Health Surveillance Secretariat (IEC/SVS/MS), sent the result of tests performed on a baby with microcephaly to the Ministry: presence of ZIKV in blood and tissues. This resulted in the Ministry of Health confirming the relationship between ZIKV and microcephaly.11

By the end of 2016, 22 countries had registered cases of congenital syndrome associated with ZIKV infection: a total of 2,525 reported cases, 2,289 (90%) of which related to Brazil.96 By December 2017, the 27 Brazilian states together recorded 3,071 microcephaly cases, 2,004 (65%) of which occurred in the Northeast region.97 This number reduced significantly to 123 new cases between January and May 2018. In all, there was a total of 3,194 records possibly associated with ZIKV infection since these began to be counted in 2015.98 Zika virus, the cause of this pandemic, had become a potential Public Health threat owing to its association with neurological complications and congenital malformations, which have been widely documented.7,8,12,18,19

The epidemics caused by the virus brought to light a broad range of clinical manifestations; although it is not possible to know the magnitude of the complications related to ZIKV infection, which may possibly be greater than those found so far. Little is known about issues such as the severity of clinical presentation of ZIKV infection or its viral load, nor about its influence on the clinical spectrum found in different places and populations.99

A descriptive study100 assessed 1,950 confirmed microcephaly cases in Brazil, 1,373 of which were in the country’s Northeast region, using secondary data obtained from the Health Ministry’s Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) relating to the period between January 1st 2015 and November 12th 2016. Its results revealed two waves of ZIKV infection: during the first wave, in 2015, there was a monthly peak of microcephaly occurrence estimated at 50 cases per 10,000 live births, most of them (70% of the total) living in the Northeast region; during the second wave, occurrence was much lower, with monthly peaks estimated as varying between 3 and 15 cases per 10,000 live births. The number of microcephaly cases related to ZIKV infection following both outbreaks, or waves, showed temporal variation according to the region of the country; the reasons for these differences have, however, yet to be enlightened.

A possible explanation for the result of these estimates is the fact that, during the second wave of infection, the relationship between ZKV infection and the microcephaly cases in question was already suspected and even supported by evidence, leading the government to broadcast campaigns with the aim of keeping the population informed. Pregnant women began to take prevention measures in order to avoid contact with the vector, such as using insect repellent, bug screens and even delaying planned pregnancy.100

Little is known about genetic variations between ZIKV lineages and their ability to interfere with ZIKV pathogenicity.101 One experimental study that used trophoblasts derived from human embryonic stem cells, found differences between the African and Asian lineages with regard to their behavior in the placenta. The occurrence of cell lysis - the process through which a cell is destroyed or dissolved by plasma membrane rupture - was only found in infections by the African ZIKV lineage; however, no differences were found in virus replication rates in relation to infection caused by the two strains. This characteristic supports the deduction that infection by an African strain at the beginning of pregnancy would probably result in miscarriage rather than congenital malformations.102

It is possible that ZIKV’s pathogenic potential depends on individual genetic variations, as indicated by a comparative experimental study of three pairs of dizygotic twins, when only one of each pair of twins was diagnosed as having ZIKV congenital syndrome. The study found that after infecting neural tissues, the virus caused delayed development of the cells of the twins who had the syndrome as well as increasing virus replication. Transcriptome analysis results showed a significant difference in DDIT4L mTOR protein inhibitor levels between twins that had the syndrome and twins that did not. The results found suggest the existence of a relationship between individual genetic disposition and increase in mTOR signaling and, given that mTOR signaling pathways are critical for autophagy mediated virus purification, ZIKV infections are intensified in these people.103

Discussion

The factors that led to large-scale and rapid emergence, spread and apparent increase in Zika virus pathogenicity in the Pacific and the Americas are not yet totally understood. It is possible that there are various mechanisms in operation, including virus mutations that might increase transmission from humans to mosquitoes, modulating the host immune response.104-107 Another factor lacking explanation is the absence of large epidemics in Africa and Asia. A hypothesis given for this fact is that it possibly reflects higher levels of immunity provided by cross-protection against other ZIKV-related flaviviruses ZIKV,104 or that epidemics that in fact existed may have been associated with dengue due to the clinical similarity between the two viruses dengue and due to their antibody cross-reactivity.37,108 Another study corroborated the hypothesis that large outbreaks have not happened in Africa because Aedes aegypti of African origin may be less susceptible to virus strains than Aedes aegypti that is not of African origin. Notwithstanding, this characteristic has not helped to explain why there have not been large outbreaks in Asia, different to the Americas, given that the populations of both regions had similar levels of susceptibility.109

Intensity of ZIKV dissemination, viremia and clinical symptoms in the Americas, including microcephaly, could have intensified owing to dengue virus immunity existing in endemic regions.110 However, a pediatric cohort study conducted in Nicaragua between January and February 2017 monitored 3,700 children aged 2 to 14 years and concluded that the opposite may occur, i.e. ZIKV infection symptoms may be reduced owing to prior dengue virus immunization.111 This hypothesis is corroborated by research involving an experiment with mice that demonstrated the effect of dengue infection on CD8+ T-cells in guaranteeing cross-protection against ZIKV during pregnancy.112 Another factor capable of intensifying dissemination was a slight genetic alteration in ZIKV polyprotein which happened before the 2013 outbreak and was sufficient to permanently increase its infectivity in human nerve cells.105 This fact would help to explain why microcephaly cases have been so numerous in the Americas in comparison to other continents.

Other aspects to be considered are related to Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus susceptibility, as well as that of ZIKV strains, due to genetic differences that influence vector response levels to infection and consequent ZIKV transmission capacity.113-120 The American strain is more easily transmitted than the Asian strain from which it is derived, this being an hypothesis confirmed by analysis of vector saliva: only the virus in the sample containing the American strain remained viable after three days of infection, in addition to having a higher infection rate in Aedes aegypti.121

The highest number of Zika and microcephaly cases was recorded in Northeast Brazil. Some reasons indicated for this were presented in an ecological analysis study: joint circulation of the virus that causes Chikungunya feber, which exists in this region, could increase the risk of other communicable diseases being transmitted.122 Another study found higher ZIKA prevalence infection in poorer social classes.123 The fact that the first notifications of infections occurred in Northeast Brazil, along with the massive media alerts that followed, helped measures to be taken that may possibly have contained greater spread of the virus in other regions. The same reasoning could be applied to Brazil, where the first infections were recorded, and to the other Latin American countries where cases were not numerous.

The Brazilian epidemic showed a sharp decline in recorded infections with effect from 2017. A possible cause of this may have been high seroprevalence in the population, leading to immunity against ZIKV.123,124 A study conducted in Bahia, a Northeastern Brazilian state, assessed 633 individuals based on their serum samples collected between 2015 and 2016. The results of the analyses showed a rapid increase in ZIKV infection seroprevalence in the population, reaching 63% in 2016.123 It is possible that population and geographic characteristics may have directly influenced the pace of propagation, and the possible reasons for this would be the variations in vector density, immunity and changes in routine habits, as well as high population mobility.100,120,123

The outbreak in the Americas has ended. Notwithstanding, a study supported by a stochastic spatial model has indicated the possibility of the emergence of new epidemics approximately every ten years, this being the time needed for a new generation of the population to become susceptible once more.124

In conclusion, the spread of ZIKV circulation seen in the last decade was the swiftest and largest recorded thus far. Possible factors contributing to this include genetic changes that increased its transmission potential, together with favorable population and geographic characteristics in the regions where the virus circulated. Large numbers of microcephaly cases were expected to occur in most countries in the Americas,99 but in the end this expectation was not confirmed. Similarly, the reasons why Brazil recorded such a higher number of cases in comparison to other Latin American countries has not been totally explained. Nor have the reasons why most of the infections recorded in Brazil were concentrated in its Northeastern region. This gives rise to several unanswered questions as to increased virus circulation and pathogenicity. Another limitation of this literature review relates to the different methods adopted in the studies consulted, thus hindering precise seroprevalence rates from being obtained. Cross-reactivity, caused by other flavivirus antibodies, was a limiting impediment to the accuracy of the results presented.76

Further research is needed to overcome gaps in knowledge about ZIKV pathogenesis and to assess local risks; seroprevalence studies to identify regions vulnerable to infection so as to foresee the potential of future epidemics. A benefit of this work is that the efforts of health authorities would be better directed, so as to contribute to the development of effective Zika virus infection control measures.

Vaccine development also needs to be encouraged, in order to interrupt the transmission chain and avoid future outbreaks and epidemics.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Brazilian Hospital Services Company (EBSERH), for its support in the development of this study.

REFERENCES

1. Faye O, Freire CCM, Iamarino A, Faye O, Oliveira JVC, Diallo M, et al. Molecular evolution of Zika Virus during its emergence in the 20 th century. PLOS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2014 Jan [citado 2019 May 8]; 8(1):e2636. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0002636 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002636 [ Links ]

2. Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, Johnson AJ, et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2008 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];14(8):1232-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/14/8/08-0287_article . doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080287 [ Links ]

3. Duffy MR, Chen T-H, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. New Engl J Med [Internet]. 2009 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];360(24):2536-43. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0805715 . doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715 [ Links ]

4. Musso D, Nilles EJ, Cao-Lormeau VM. Rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2014 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];20(10):O595-6. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(14)65391-X/fulltext . doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12707 [ Links ]

5. Roth A, Mercier A, Lepers C, Hoy D, Duituturaga S, Benyon E, et al. Concurrent outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus infections - an unprecedented epidemic wave of mosquito-borne viruses in the Pacific 2012 - 2014. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2014 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];19(41):pii:20929. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.41.20929 [ Links ]

6. Cao-Lormeau VM, Roche C, Teissier A, Robin E, Berry AL, Mallet HP, et al. Zika virus, French Polynesia, South Pacific, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];20(6):1085-6. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/20/6/14-0138_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140138 [ Links ]

7. Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, Ramos AMO, Davi HOF, Iglezias AD, Kanamura CT, et al. Pathology of congenital Zika syndrome in Brazil: a case series. Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];388(10047):898-904. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)30883-2/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30883-2 [ Links ]

8. Costello A, Dua T, Duran P, Gülmezoglu M, Oladapo OT, Perea W, et al. Defining the syndrome associated with congenital Zika virus infection. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2016 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];94(6):406-406A. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4890216/ . doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.176990 [ Links ]

9. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria MS/GM no 1.813, de 11 de novembro de 2015. Declara Emergência em Saúde Pública de importância Nacional (ESPIN) por alteração do padrão de ocorrência [Internet]. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF), 2015 nov 12; Seção 1:51. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2015/prt1813_11_11_2015.html [ Links ]

10. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Epidemiological alert increase of microcephaly in the northeast of Brazil [Internet]. 2015 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2015/2015-nov-17-cha-microcephaly-epi-alert.pdf [ Links ]

11. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Ministério da Saúde confirma relação entre vírus Zika e microcefalia [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2015 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.blog.saude.gov.br/index.php/combate-ao-aedes/50399-ministerio-da-saude-confirma-relacao-entre-virus-zika-e-microcefalia [ Links ]

12. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications for public health in the Americas [Internet]. 2015 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32405&lang=en [ Links ]

13. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/emergency-committee-zika-microcephaly/en/ [ Links ]

14. World Health Organization. WHO statement on the first meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR (2005)) Emergency Committee on Zika virus and observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/1st-emergency-committee-zika/en/ [ Links ]

15. Oehler E, Watrin L, Larre-Goffart P, Lastère S, Valour F, Baudouin L, et al. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barré syndrome - case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2014 Mar[citado 2019 May 8];19(9):pii:20720. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.9.20720 [ Links ]

16. Cao-lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastere S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak caused by ZIKA virus infection in French Polynesia. Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Apr [citado 2019 May 8];387(10027):1531-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5444521/ . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6 [ Links ]

17. Araújo TVB, Rodrigues LC, Ximenes RAA, Miranda Filho DB, Montarroyos UR, Melo APL, et al. Association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly in Brazil, January to May, 2016: preliminary report of a case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Dec [citado 2019 May 8];16(12):1356-63. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(16)30318-8/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30318-8 [ Links ]

18. Krauer F, Riesen M, Reveiz L, Oladapo OT, Porgo TV, Haefliger A, et al. Zika Virus infection as a cause of congenital brain abnormalities and Guillain - Barre Syndrome: systematic review. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2017 Jan [citado 2019 May 8];14(1):e1002203. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002203 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002203 [ Links ]

19. Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika Virus and Birth defects - reviewing the evidence for causality. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2016 May [citado 2019 May 8];374(20):1981-7. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsr1604338 . doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338 [ Links ]

20. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Informe epidemiológico no 57 - semana epidemiológica (SE) 52/2016 (25 a 31/12/2016) - monitoramento dos casos de microcefalia no Brasil [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017 [citado 2019 maio 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://combateaedes.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/Informe-Epidemiologico-n57-SE-52_2016-09jan2017.pdf [ Links ]

21. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Zika suspected and confirmed cases reported by countries and territories in the Americas Cumulative cases, 2015-2017. Updated as of 04 January 2018 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2017 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=43296-zika-cumulative-cases-4-january-2018-296&category_slug=cumulative-cases-pdf-8865&Itemid=270&lang=en [ Links ]

22. Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. Zika virus (I) isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1952 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];46(5):509-20. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12995440 [ Links ]

23. Dick GW. Zika virus (II). Pathogenicity and physical properties. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1952 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];46(5):521-34. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0035920352900436 . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90043-6 [ Links ]

24. Dick GW. Epidemiological notes on some viruses isolated in Uganda (Yellow fever, Rift Valley fever, Bwamba fever, West Nile, Mengo, Semliki forest, Bunyamwera, Ntaya, Uganda S and Zika viruses). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1953 Jan [citado 2019 May 8];47(1)13-48. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article/47/1/13/1901421 . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(53)90021-2 [ Links ]

25. Macnamara FN, Horn DW, Porterfield JS. Yellow fever and other arthropod-borne viruses. A consideration of two serological surveys made in South Western Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1959 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];53(2):202-12. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13647627 [ Links ]

26. Smithburn KC. Neutralizing antibodies against certain recently isolated viruses in the sera of human beings residing in East Africa. J Immunol [Internet]. 1952 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];69(2):223-34. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/69/2/223.long [ Links ]

27. Smithburn KC. Neutralizing antibodies against arthropod-borne viruses in the sera of long-time residents of Malaya and borneo. Am J Hyg. 1954 Mar;59(2):157-63. [ Links ]

28. MacNamara FN. Zika virus: a report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1954 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];48(2):139-45. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0035920354900061 . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(54)90006-1 [ Links ]

29. Weinbren MP, Williaams MC. Zika virus: further isolations in the zka area, and some studies on the strains isolated. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1958 May;52(3):263-8. [ Links ]

30. Kokernot RH, Smithburn KC, Gandara AF, Mcintosh BM, Heymann CS. Neutralization tests with sera from individuals residing in Mozambique against specific viruses isolated in Africa, transmitted by arthropods. An Inst Med Trop (Lisb). 1960 Jan-Jun;17:201-30. [ Links ]

31. Pellissier A. Serological investigation on the incidence of neurotropic viruses in French Equatorial Africa. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Fil. 1954;47(2):223-27. [ Links ]

32. Smithburn KC, Kerr, JA,Gatne PB. Neutralizing antibodies against certain viruses in the sera of residents of India. J Immunol. 1954 Apr;72(4):248-57. [ Links ]

33. Pond WL. Arthropod-borne virus antibodies in sera from residents of South-East Asia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1963 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];57(5):364-71. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0035920363901007 . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(63)90100-7 [ Links ]

34. Hammon WM, Schrack Jr WD, Sather GE. Serological survey for arthropod-borne virus infections in the Philippines. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1958 May [citado 2019 May 8];7(3):323-8. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.ajtmh.org/content/journals/10.4269/ajtmh.1958.7.323 . doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1958.7.323 [ Links ]

35. Regan RL, Brueckner AL. Comparison by electron microscopy of the Ntaya and Zika viruses. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1953;11(2):347-51. [ Links ]

36. Boorman JPT, Porterfield JS. A simple technique for infection of mosquitoes with viruses transmission of Zika virus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1956 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];50(3):238-42. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article-abstract/50/3/238/1899150?redirectedFrom=fulltext . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(56)90029-3 [ Links ]

37. Haddow AD, Schuh AJ, Yasuda CY, Kasper MR, Heang V, Guzman H, et al. Genetic characterization of Zika Virus strains: geographic expansion of the Asian lineage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2012 [citado 2019 May 8];6(2):e1477. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477 [ Links ]

38. Marchette NJ, Garcia R, Rudnick A. Isolation of Zika virus from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Malaysia. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1969 May [citado 2019 May 8];18(3):411-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.ajtmh.org/content/journals/10.4269/ajtmh.1969.18.411 . doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1969.18.411 [ Links ]

39. Henderson BE, Metselaar D, Cahill K, Timms GL, Tukei PM, Williams MC. Yellow fever immunity surveys in northern Uganda and Kenya and Eastern Somalia, 1966-67. Bull World Heal Organ [Internet]. 1968 [citado 2019 May 8];38(2):229-37. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2554316/ [ Links ]

40. Brès P. Données récentes apportées par les enquêtes sérologiques sur la prévalence des arbovirus en Afrique, avec référence spéciale à la fièvre jaune. Bull World Heal Organ [Internet]. 1970 [citado 2019 May 8];43(2):223-67. Availble from: Availble from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2427644/ [ Links ]

41. Kokernot RH, Casaca VM, Weinbren MP, McIntosh BM. Survey for antibodies against arthropod-borne viruses in the sera of indigenous residents of Angola. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1965 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];59(5):563-70. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article-abstract/59/5/563/1913859?redirectedFrom=fulltext . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(65)90159-8 [ Links ]

42. Chippaux-Hyppolite C. Immunologic investigation on the frequency of arbovirus in man in the Central African Republic. Preliminary note. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1965 Sep-Oct;58(5):812-20. [ Links ]

43. Salaun JJ, Brottes H. Arboviruses in Cameroun: serologic investigation. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1967 [Internet];37(3):343-61. Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2554275/ [ Links ]

44. Bres P, Lacan A, Diop I, Michel R, Peretti P, Vidal C. Arborviruses in Senegal: serological survey. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Fil. 1963 May-Jun;56:384-402. [ Links ]

45. Pinto MR. Survey for antibodies to arboviruses in the sera of children in Portuguese Guinea. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1967 [citado 2019 May 8];37(1):101-8. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2554218/ [ Links ]

46. Renaudet J, Jan C, Ridet J, Adam C, Robin Y. A serological survey of arboviruses in the human population of Senegal. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1978 Mar-Apr;71(2):131-40. [ Links ]

47. Monlun E, Zeller H, Le Guenno B, Traoré-Lamizana M, Hervy JP, Adam F, et al. Surveillance of the circulation of arbovirus of medical interest in the region of eastern Senegal. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86(1):21-8. [ Links ]

48. Akoua-Koffi C, Diarrassouba S, Bénié VB, Ngbichi JM, Bozoua T, Bosson A, et al. Investigation autour d’un cas mortel de fièvre jaune en Côte d’Ivoire en 1999. Bull Soc Pathol Exot [Internet]. 2001 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];94(3):227-30. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/39846303.pdf [ Links ]

49. Sérié C, Casals J, Panthier R, Brès P, Williams MC. Studies on yellow fever in Ethiopia. 2. Serological study of the human population. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1968 [citado 2019 May 8];38(6):843-54. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2554526/ [ Links ]

50. Geser A, Henderson BE, Christensen S. A multipurpose serological survey in Kenya. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1970 [citado 2019 May 8];43(4):539-52. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2427766/ [ Links ]

51. McCrae AW, Kirya BG. Yellow fever and Zika virus epizootics and enzootics in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1982 [citado 2019 May 8];76(4):552-62. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0035920382901614 . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(82)90161-4 [ Links ]

52. Haddow AJ, Williams MC, Woodall JP, Simpson DI, Goma LK. Twelve isolations of zika virus from aedes (stegomyia) africanus (theobald) taken in and above a uganda forest. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1964 [citado 2019 May 8];31:57-69. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2555143/ [ Links ]

53. Fagbami AH. Zika virus infections in Nigeria: virological and seroepidemiological investigations in Oyo State. J Hyg (Lond) [Internet]. 1979 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];83(2):213-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2129900/ [ Links ]

54. Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Foy JLC, Blitvich BJ, Travassos da Rosa A, Haddow AD, et al. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011 May [citado 2019 May 8];17(5):880-2. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3321795/ . doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101939 [ Links ]

55. Musso D, Roche C, Robin E, Nhan T, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau VM. Potential sexual transmission of Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Feb [citado 2019 May 8];21(2):359-61. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4313657/ . doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141363 [ Links ]

56. Frank C, Cadar D, Schlaphof A, Neddersen N, Günther S, Tappe D, et al. Sexual transmission of Zika virus in Germany, April 2016. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2016 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];21(23). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.23.30252 . doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.23.30252 [ Links ]

57. Driggers RW, Ho C-Y, Korhonen EM, Kuivanen S, Jääskeläinen AJ, Smura T, et al. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2016 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];374(22):2142-51. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1601824?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov . doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824 [ Links ]

58. Brasil P, Pereira JP, Moreira ME, Nogueira RMR, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2016 Dec [citado 2019 May 8];375(24):2321-4. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1602412 . doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412 [ Links ]

59. Aubry M, Finke J, Teissier A, Roche C, Broult J, Paulous S, et al. Seroprevalence of arboviruses among blood donors in French Polynesia, 2011-2013. Int J Infect Dis[Internet]. 2015 Dec [citado 2019 May 8];41:11-2. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(15)00239-8/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.005 [ Links ]

60. Pettersson JHO, Bohlin J, Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, Brynildsrud OB, Alfsnes K, Cao-Lormeau VM, et al. Re-visiting the evolution, dispersal and epidemiology of Zika virus in Asia article. Emerg Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2018 May [citado 2019 May 8];7(1):79. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1038/s41426-018-0082-5 . doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0082-5 [ Links ]

61. Sun J, Fu T, Mao H, Wang Z, Pan J, Rutherford S, et al. A cluster of Zika virus infection in a Chinese tour group returning from Fiji and Samoa. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2017 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];7:43527. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5361211/ . doi: 10.1038/srep43527 [ Links ]

62. Tognarelli J, Ulloa S, Villagra E, Lagos J, Aguayo C, Fasce R, et al. A report on the outbreak of Zika virus on Easter Island, South Pacific, 2014. Arch Virol [Internet]. 2016 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];161(3):665-8. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00705-015-2695-5 . doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2695-5 [ Links ]

63. Pyke AT, Daly MT, Cameron JN, Moore PR, Taylor CT, Humphreys JL, et al. Imported Zika virus infection from the cook islands into Australia, 2014. PLoS Curr [Internet]. 2014 Jun [citado 2019 May 8]; 2014; 6:pii. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://currents.plos.org/outbreaks/index.html%3Fp=38348.html [ Links ]

64. Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, O'Connor O, Calvez E, Daures M, John M, Grangeon J, et al. Co-infection with Zika and dengue viruses in 2 patients, New Caledonia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Feb [citado 2019 May 8];21(2):381-2. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/2/14-1553_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141553 [ Links ]

65. Heang V, Yasuda CY, Sovann L, Haddow AD, Travassos da Rosa AP, Tesh RB, et al. Zika virus infection, Cambodia, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2012 Feb [citado 2019 May 8];18(2):349-51. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3310457/ . doi: 10.3201/eid1802.111224 [ Links ]

66. Kwong JC, Druce JD, Leder K. Case report : Zika virus infection acquired during brief travel to Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2013 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];89(3):516-7. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3771291/ . doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0029 [ Links ]

67. Perkasa A, Yudhaputri F, Haryanto S, Yohan B, Myint KS, Ledermann JP, et al. Isolation of Zika virus from febrile patient, Indonesia fatal. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 May [citado 2019 May 8];22(5):924-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/5/15-1915_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151915 [ Links ]

68. Tappe D, Nachtigall S, Kapaun A, Schnitzler P, Günther S, Schmidt-Chanasit J. Acute Zika virus infection after travel to Malaysian Borneo, September 2014. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 May [citado 2019 May 8];21(5):911-3. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/5/14-1960_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2105.141960 [ Links ]

69. Alera MT, Hermann L, Tac-An IA, Klungthong C, Villa D, Thaisomboonsuk B, et al. Zika virus infection, Philippines, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Apr [citado 2019 May 8];21(4):722-4. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4378478/ . doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141707 [ Links ]

70. Korhonen EM, Huhtamo E, Smura T, Kallio-Kokko H, Raassina M, Vapalahti O. Zika virus infection in a traveller returning from the Maldives, June 2015. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2016 [citado 2019 May 8];21(2). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.2.30107 . doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.2.30107 [ Links ]

71. Buathong R, Hermann L, Thaisomboonsuk B, Rutvisuttinunt W, Klungthong C, Chinnawirotpisan P, et al. Detection of Zika virus infection in Thailand , 2012-2014. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2015 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];93(2):380-3. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4530765/ . doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0022 [ Links ]

72. Tappe D, Rissland J, Gabriel M, Emmerich P, Günther S, Held G, et al. First case of laboratory-con fi rmed Zika virus infection imported into Europe, November 2013. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2014 Jan [citado 2019 May 8];19(4):pii: 20685. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.4.20685 [ Links ]

73. Campos GS, Bandeira AC, Sardi SI. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];21(10):1885-6. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/10/15-0847_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150847 [ Links ]

74. Zanluca C, Melo VC, Mosimann AL, Santos GI, Santos CN, Luz K. First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz [Internet]. 2015 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];110(4):569-72. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/mioc/v110n4/0074-0276-mioc-0074-02760150192.pdf . doi: 10.1590/0074-02760150192 [ Links ]

75. Fantinato FFST, Araújo ELL, Ribeiro IG, Andrade MR, Dantas ALM, Rios JMT, et al. Descrição dos primeiros casos de febre pelo vírus Zika investigados em municípios da região Nordeste do Brasil, 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde [Internet]. 2016 out-dez [citado 2019 maio 8];25(4):683-90. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ress/v25n4/2237-9622-ress-S1679_49742016000400002.pdf . doi: 10.5123/s1679-49742016000400002 [ Links ]

76. Felix AC, Souza NCS, Figueiredo WM, Costa AA, Inenami M, Silva RMG, et al. Cross reactivity of commercial anti-dengue immunoassays in patients with acute Zika virus infection. J Med Virol [Internet]. 2017 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];89(8)1477-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jmv.24789 . doi: 10.1002/jmv.24789 [ Links ]

77. Bozza FA, Moreira-Soto A, Rockstroh A, Fischer C, Nascimento AD, Calheiros AS, et al. Differential shedding and antibody kinetics of Zika and Chikungunya viruses, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Feb [citado 2019 May 8];25(2):311-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/25/2/18-0166_article [ Links ]

78. Waggoner JJ, Pinsky A. Zika virus : diagnostics for an emerging pandemic threat. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2016 Apr [citado 2019 May 8];54(4):860-7. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://jcm.asm.org/content/54/4/860.long . doi: 10.1128/JCM.00279-16 [ Links ]

79. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (EUA). Revised diagnostic testing for Zika, chikungunya, and dengue viruses in US Public Health Laboratories [Internet]. 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/denvchikvzikv-testing-algorithm.pdf [ Links ]

80. Yun S, Song B, Frank JC, Julander JG, Polejaeva IA, Davies CJ, et al. Complete genome sequences of three historically important, spatiotemporally distinct, and genetically divergent strains of Zika virus: MR-766, P6-740, and PRVABC-59. Genome Announc [Internet]. 2016 Jul-Aug [citado 2019 May 8];4(4):e00800-16. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://mra.asm.org/content/4/4/e00800-16 . doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00800-16 [ Links ]

81. Faria NR, Azevedo RDSDS, Kraemer MUG, Souza R, Cunha MS, Hill SC, et al. Zika virus in the Americas: early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science [Internet]. 2016 Apr [citado 2019 May 8];375(6283):345-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/352/6283/345.long. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5036 [ Links ]

82. Metsky H, Matranga C, Wohl S, Schaffner S, Freije C, Winnicki S, et al. Zika virus evolution and spread in the Americas. Nature [Internet]. 2017 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];546(7658):411-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature22402 [ Links ]

83. Naccache SN, Thézé J, Sardi SI, Somasekar S, Greninger AL, Bandeira AC, et al. Distinct zika virus lineage in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];22(10):1788-92. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/10/16-0663_article [ Links ]

84. Musso D, Cao-Lormeau VM, Gubler DJ. Zika virus: following the path of dengue and chikungunya? Lancet [Internet]. 2015 Jul [citado 2019 May 8]; 386(9990):243-4. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)61273-9/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61273-9 [ Links ]

85. Campos TDL, Durães-carvalho R, Rezende AM, Carvalho OV, Kohl A, Wallau GL, et al. Revisiting key entry routes of human epidemic arboviruses into the Mainland Americas. Int J Genomics [Internet]. 2018 Oct [citado 2019 May 8]; 2018:1-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijg/2018/6941735/cta/ [ Links ]

86. Thézé J, Li T, Plessis L, Bouquet J, Kraemer MUG, Somasekar S, et al. Genomic epidemiology reconstructs the introduction and spread of Zika virus in Central America and Mexico. Cell Host Microbe [Internet]. 2018 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];23(6):855-64.e7. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.cell.com/cell-host-microbe/fulltext/S1931-3128(18)30218-X?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS193131281830218X%3Fshowall%3Dtrue . doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.04.017 [ Links ]

87. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Zika epidemiological update: 22 September 2016 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2016/2016-sep-22-cha-epi-update-zika-virus.pdf [ Links ]

88. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Zika epidemiological update: 29 December 2016 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2016/2016-dec-29-phe-epi-update-zika-virus.pdf [ Links ]

89. Ikejezie J, Shapiro CN, Kim J, Chiu M, Almiron M, Ugarte C, et al. Zika virus transmission - region of the Americas. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017 Mar [citado 2019 Mar 8];66(12):329-34. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6612a4.htm [ Links ]

90. World Health Organization. Fifth meeting of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (2005) regarding microcephaly, other neurological disorders and Zika virus [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/zika-fifth-ec/en/ [ Links ]

91. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Ministério da Saúde declara fim da emergência nacional para Zika [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017 [citado 2019 maio 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.brasil.gov.br/noticias/saude/2017/05/ministerio-da-saude-declara-fim-da-emergencia-nacional-para-zika [ Links ]

92. Nóbrega MEB, Araújo ELL, Wada MY, Leite PL, Percio J, Dimech GS. Surto de síndrome de Guillain-Barré possivelmente relacionado à infecção prévia pelo vírus Zika, Região Metropolitana do Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil, 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde [Internet]. 2018 [citado 2019 maio 8];27(2):e2017039.Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ress/v27n2/2237-9622-ress-27-02-e2017039.pdf . doi: 10.5123/s1679-49742018000200016 [ Links ]

93. Malta JM, Vargas A, Leite PL, Percio J, Coelho GE, Ferraro AH, et al. Síndrome de Guillain-Barré e outras manifestações neurológicas possivelmente relacionadas à infecção pelo vírus Zika em municípios da Bahia, 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saúde [Internet]. 2017 jan-mar [citado 2019 maio 8];26(1):9-18. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ress/v26n1/2237-9622-ress-26-01-00009.pdf . doi: 10.5123/s1679-49742017000100002 [ Links ]

94. Nogueira ML, Estofolete CF, Terzian ACB, Mascarin do Vale EPB, Silva RC, Silva RF, et al. Zika virus infection and solid organ transplantation: a new challenge. Am J Transplant [Internet]. 2017 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];17(3)791-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ajt.14047 . doi: 10.1111/ajt.14047 [ Links ]

95. Vargas A, Saad E, Dimech GS, Santos RH, Sivini MAVC, Albuquerque LC, et al. Características dos primeiros casos de microcefalia possivelmente relacionados ao vírus Zika notificados na região metropolitana de Recife, Pernambuco. Epidemiol Serv Saúde [Internet]. 2016 out-dez [citado 2019 maio 8];25(4):691-700. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ress/v25n4/2237-9622-ress-S1679_49742016000400003.pdf . doi: 10.5123/s1679-49742016000400003 [ Links ]

96. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Zika suspected and confirmed cases reported by countries and territories in the Americas Cumulative cases, 2015-2016. Updated as of 29 December 2016 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2016 [citado 2019 May 8]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2016/2016-dec-29-phe-ZIKV-cases.pdf [ Links ]

97. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Monitoramento integrado de alterações no crescimento e desenvolvimento relacionadas à infecção pelo vírus Zika e outras etiologias infecciosas, até a Semana 52 de 2017. Bol Epidemiol [Internet]. 2018 [citado 2019 maio 8];49(6):1-10. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2018/fevereiro/20/2018-003-Final.pdf [ Links ]

98. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Monitoramento integrado de alterações no crescimento e desenvolvimento relacionadas à infecção pelo vírus Zika e outras etiologias infecciosas, até a Semana Epidemiológica 20 de 2018. Bol Epidemiol [Internet]. 2018 [citado 2019 maio 8];49(6). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2018/junho/29/Monitoramento-integrado-de-alteracoes-no-crescimento-e-desenvolvimento-relacionadas-a-infeccao-pelo-virus-Zika.pdf [ Links ]

99. Rodrigues LC, Paixao ES. Risk of Zika-related microcephaly: stable or variable? Lancet [Internet]. 2017 Aug [citado 2019 May 8]; 390(10097):824-6. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31478-2/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31478-2 [ Links ]

100. Oliveira WK, França GVA, Carmo EH, Duncan BB, Souza Kuchenbecker R, Schmidt MI. Infection-related microcephaly after the 2015 and 2016 Zika virus outbreaks in Brazil: a surveillance-based analysis. Lancet [Internet]. 2017 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];390(10097):861-70. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31368-5/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31368-5 [ Links ]

101. Wang L, Valderramos SG, Wu A, Ouyang S, Li C, Brasil P, et al. From mosquitos to humans: genetic evolution of Zika virus. Cell Host Microbe [Internet]. 2016 May [citado 2019 May 8];19(5):561-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5648540/ . doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.006 [ Links ]

102. Sheridan MA, Balaraman V, Schust DJ, Ezashi T, Michael Roberts R, Franz AWE. African and Asian strains of Zika virus differ in their ability to infect and lyse primitive human placental trophoblast. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018 [citado 2019 May 8];13(7):e0200086. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6037361/ . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200086 [ Links ]

103. Caires-Júnior LC, Goulart E, Melo US, Araujo BHS, Alvizi L, Soares-Schanoski A, et al. Discordant congenital Zika syndrome twins show differential in vitro viral susceptibility of neural progenitor cells. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2018 Feb [citado 2019 May 8];Dec;9(1):475. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02790-9 . doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02790-9 [ Links ]

104. Pettersson JH, Eldholm V, Seligman SJ, Lundkvist A, Falconar AK, Gaunt MW, et al. How did Zika virus emerge in the Pacific Islands and Latin America? MBio [Internet]. 2016 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];7(5):pii:e01239-16. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://mbio.asm.org/content/7/5/e01239-16 . doi: 10.1128/mBio.01239-16 [ Links ]

105. Yuan L, Huang XY, Liu ZY, Zhang F, Zhu XL, Yu JY, et al. A single mutation in the prM protein of Zika virus contributes to fetal microcephaly. Science [Internet]. 2017 Nov [citado 2019 May 8];358(6365):933-6. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/358/6365/933 . doi: 10.1126/science.aam7120 [ Links ]

106. Li J, Xiong Y, Wu W, Liu X, Qu J, Zhao X, et al. Zika virus in a traveler returning to China from Caracas, Venezuela, February 2016. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];22(6):1133-6. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/6/16-0273_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2206.160273 [ Links ]

107. Xia H, Luo H, Shan C, Muruato AE, Nunes BTD, Medeiros DBA, et al. An evolutionary NS1 mutation enhances Zika virus evasion of host interferon induction. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2018 Jan [citado 2019 May 8];9(1):414. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02816-2 [ Links ]

108. Lanciotti RS, Lambert AJ, Holodniy M, Saavedra S, Signor LC. Phylogeny of Zika virus in Western hemisphere, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016 May [citado 2019 May 8];22(5):933-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/5/16-0065_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2205.160065 [ Links ]

109. Aubry F, Martynow D, Baidaliuk A, Merkling SH, Dickson LB, Romero-Vivas CM, et al. Worldwide survey reveals lower susceptibility of African Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to diverse strains of Zika virus. bioRxiv Prepr [Internet]. 2018 Jun [citado 2019 May 8];1-8. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/06/10/342741.full.pdf . doi: 10.1101/342741 [ Links ]

110. Bardina SV, Bunduc P, Tripathi S, Duehr J, Frere JJ, Brown JA, et al. Enhancement of Zika virus pathogenesis by preexisting antiflavivirus immunity. Science [Internet]. 2017 Apr [citado 2019 May 8];356(6334):175-80. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6334/175.long . doi: 10.1126/science.aal4365 [ Links ]

111. Gordon A, Gresh L, Ojeda S, Katzelnick LC, Sanchez N, Mercado JC, et al. Prior dengue virus infection and risk of Zika: a pediatric cohort in Nicaragua. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2019 Jan [citado 2019 May 8];16(1):e1002726. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002726 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002726 [ Links ]

112. Shresta S, Viramontes KM, Wang Y-T, Huynh A-T, Diamond MS, Elong Ngono A, et al. Cross-reactive Dengue virus-specific CD8+ T cells protect against Zika virus during pregnancy. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2018 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];9(1):3042. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05458-0 . doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05458-0 [ Links ]

113. Weger-Lucarelli J, Rückert C, Chotiwan N, Nguyen C, Garcia Luna SM, Fauver JR, et al. Vector competence of American mosquitoes for three strains of Zika virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2016 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];10(10):e0005101. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0005101 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005101 [ Links ]

114. Ciota AT, Bialosuknia SM, Zink SD, Brecher M, Ehrbar DJ, Morrissette MN, et al. Effects of Zika virus strain and Aedes mosquito species on vector competence. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017 Jul [citado 2019 May 8];23(7):1110-7. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/7/16-1633_article . doi: 10.3201/eid2307.161633 [ Links ]

115. Azar SR, Roundy CM, Rossi SL, Huang JH, Leal G, Yun R, et al. Differential vector competency of aedes albopictus populations from the Americas for Zika Virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2017 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];97(2):330-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5544086/ . doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0969 [ Links ]

116. Angleró-Rodríguez YI, MacLeod HJ, Kang S, Carlson JS, Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G. Aedes aegypti molecular responses to Zika virus: modulation of infection by the toll and Jak/Stat immune pathways and virus host factors. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2017 Oct [citado 2019 May 8];8:2050. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02050/full . doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02050 [ Links ]

117. Di Luca M, Severini F, Toma L, Boccolini D, Romi R, Remoli ME, et al. Experimental studies of susceptibility of Italian Aedes albopictus to Zika virus. Euro Surveill [Internet]. 2016 May [citado 2019 May 8];21(18). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.18.30223 . doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.18.30223 [ Links ]

118. Richard V, Paoaafaite T, Cao-Lormeau VM. Vector competence of French Polynesian aedes aegypti and aedes polynesiensis for Zika virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2016 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];10(9):e0005024. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0005024 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005024 [ Links ]

119. Hall-Mendelin S, Pyke AT, Moore PR, Mackay IM, McMahon JL, Ritchie SA, et al. Assessment of local mosquito species incriminates aedes aegypti as the potential vector of Zika virus in Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2016 Sep [citado 2019 May 8];10(9):e0004959. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5028067/ . doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004959 [ Links ]

120. Chouin-Carneiro T, Vega-Rua A, Vazeille M, Yebakima A, Girod R, Goindin D, et al. Differential susceptibilities of aedes aegypti and aedes albopictus from the Americas to Zika virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2016 Mar [citado 2019 May 8];10(3):e0004543. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0004543 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004543 [ Links ]

121. Pompon J, Morales-Vargas R, Manuel M, Huat Tan C, Vial T, et al. A Zika virus from America is more efficiently transmitted than an Asian virus by aedes aegypti mosquitoes from Asia. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2017 Apr [citado 2019 May 8];7(1):1215. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-01282-6 . doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01282-6 [ Links ]

122. Campos MC, Dombrowski JG, Phelan J, Marinho CRF, Hibberd M, Clark TG, et al. Zika might not be acting alone: using an ecological study approach to investigate potential co-acting risk factors for an unusual pattern of microcephaly in Brazil. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018 Aug [citado 2019 May 8];13(8)e0201452. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0201452 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201452 [ Links ]

123. Martins Netto E, Moreira-Soto A, Pedroso C, Höser C, Funk S, Kucharski A, et al. High Zika virus Seroprevalence in Salvador, Northeastern Brazil limits the potential for further outbreaks. MBio [Internet]. 2017 Nov [citado 2019 May 8];8(6):pii:e01390-17. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://mbio.asm.org/content/8/6/e01390-17 . doi: 10.1128/mBio.01390-17 [ Links ]

124. Ferguson NM, Cucunubá ZM, Dorigatti I, Nedjati-gilani GL, Donnelly CA, Basáñez MG, et al. Countering the Zika epidemic in Latin America. Science [Internet]. 2016 Jul [citado 2019 May 8];353(6297):353-4. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/353/6297/353/tab-pdf . doi: 10.1126/science.aag0219 [ Links ]

125. Chippaux HC, Chippaux A. Yellow fever antibodies in children in the Central African Republic. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1966 [citado 2019 May 8];34(1):105-11. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2475960/ [ Links ]

126. Robin Y, Brès P, Lartigue JJ, Gidel R, Lefèvre M, Athawet B, Hery G. Arboviruses in Ivory Coast. Serologic survey in the human population. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Fil. 1968 Nov-Dec;61(6):833-45. [ Links ]

127. Henderson BE, Metselaar D, Kirya GB, Timms GL. Investigations into yellow fever virus and other arboviruses in the northern regions of Kenya. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1970 [citado 2019 May 8];42(5):787-95. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2427481/ [ Links ]

128. Fagbami AH, Fabiyi A, Monath TP. Dengue virus infections in nigeria: a survey for antibodies in monkeys and humans. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1977 [citado 2019 May 8];71(1):60-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article-abstract/71/1/60/1934880?redirectedFrom=fulltext. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(77)90210-3 [ Links ]

129. Olson JG, Ksiazek TG, Suhandiman T. Zika virus, a cause of fever in Central Java, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1981 Jan [citado 2019 May 8];75(3):389-93. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article-abstract/75/3/389/1881699?redirectedFrom=fulltext . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90100-0 [ Links ]

130. Olson JG, Ksiazenk TG, Gubler DJ, Lubist SI, Simanjuntak G, Lee VH, et al. A survey for arboviral antibodies in sera of humans and animals in lombok, Republic of Indonesia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1983 Apr;77(2):131-7. [ Links ]

131. Darwish MA, Hoogstraal H, Roberts TJ, Ahmed IP, Omar F. A sero-epidemiological survey for certain in Pakistan arboviruses ( Togaviridae ). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1983 [citado 2019 May 8];77(4):442-5. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0035920383901062 . doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90106-2 [ Links ]

132. Robin Y, Mouchet J. Serological and entomological study on yellow fever in Sierra Leone. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1975 May-Jun;68(3):249-58. [ Links ]

133. Monath TP, Wilson DC, Casals J. The 1970 yellow fever epidemic in Okwoga District, Benue Plateau State, Nigeria. 3. Serological responses in persons with and without pre-existing heterologous group B immunity. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1973 [citado 2019 May 8];49(3):235-44. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2481145/ [ Links ]

134. Moore DL, Causey OR, Carey DE, Reddy S, Cooke AR, Akinkugbe FM, et al. Arthropod-borne viral infections of man in nigeria, 1964-1970. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1975 Mar;69(1):49-64. [ Links ]

135. Filipe AR, Carvalho RG, Relvas A, Casaca V. Arbovirus studies in Angola: serological survey for antibodies to arboviruses. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1975 May [citado 2019 May 8];24(3):516-20. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.ajtmh.org/content/journals/10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.516 . doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.516 [ Links ]

136. Omer AH, McLaren ML, Johnson BK, Chanas AC, Brumpt I, Gardner P, et al. A seroepidemiological survey in the Gezira, Sudan, with special reference to arboviruses. J Trop Med Hyg. 1981 Apr;84(2):63-6. [ Links ]