Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.28 no.3 Brasília set. 2019 Epub 20-Jan-2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742019000300017

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Structure for the work and composition of Family Health Support Unit teams: national survey - Program for Improving Primary Health Care Access and Quality (PMAQ), 2013*

1Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Física, Pelotas, RS, Brazil

2Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Faculdade de Medicina, Departamento de Medicinal Social, Pelotas, RS, Brazil

3Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Faculdade de Enfermagem, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Enfermagem, Pelotas, RS, Brazil

Objective:

to describe the structure of Family Health Support Unit (FHSU) teams with regard to physical space, training received, continuing education and professionals that support Primary Health Care (PHC) teams in Brazil, in 2013.

Methods:

this is a descriptive study using data from the external evaluation stage of the Program for Improving Primary Health Care Access and Quality (PMAQ).

Results:

the 1,773 FHSU teams mainly used shared clinics at primary health care centers (85.7%); 63.4% of professionals were offered specific training when they started work at their FHSU, while 67.4% were offered continuing education; the teams received support mainly from physiotherapists (87.4%) and Physical Education professionals (87,0%).

Conclusion:

the structure available for FHSU teams is in accordance with the guidelines; some FHSU professionals have not received any specific training for the job.

Keywords: Structure of Services; Primary Health Care; Health Evaluation; Patient Care Team

Introduction

Primary Health Care (PHC), in addition to being the main entry point for accessing the Brazilian health system, is capable of providing solutions for some 85% of the population’s health demands.1 The Family Health Support Units (FHSU) were created in 2008, with the aim of qualifying and broadening the scope of PHC actions through multiprofessional teams. In view of their relevance, evaluation of the Family Health Support Units is an important issue.2

Health service evaluation is a quality control mechanism.3 Continually monitoring health service provision enables early detection and correction of deviation from established standards so that services can be better developed and enhanced.4

In Brazil, the objective of the Program for Improving Primary Health Care Access and Quality (PMAQ) is to induce increased access to PHC and improvement of its quality, guaranteeing a nationally comparable standard of quality, so as to enable greater transparency and effectiveness of government actions directed towards Primary Health Care. PMAQ takes place by means of evaluations based on questions ranging from PHC service infrastructure to team work processes and service user satisfaction. These evaluations are carried out by means of observation of service facilities, interviews with PHC service teams (Family Health Strategy, FHSU teams and parameterized teams) as well as with service users.5

Service structure can influence health outcomes, i.e., good structure favors good processes and, consequently, increases the occurrence of positive outcomes.6 The structure of a health service is related to its physical area, human, material and financial resources available to it, including health professional training and service organization.7

Despite the relevance of FHSU for PHC, literature is still scarce on the structure available for the work done by FHSU.8 The objective of this study was to describe FHSU structure with regard to physical space used, training and continuing education received by the professionals who provide support to the PHC teams.

Methods

This is a descriptive study using data from the external evaluation stage of PMAQ Cycle II. Teams were included when municipal health service management adhered to the program. Following the external evaluation process the teams were progressively certified and received funding based on their performance. PMAQ was developed by the Federal Government and carried out by 41 Federal Teaching and Research Institutions led by: the Oswaldo Cruz Institute Foundation (Fiocruz), the Federal University of Bahia (UFBa), the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel), the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) and the Federal University of Piauí (UFPi).9

PMAQ is divided into four stages of a cyclical process, namely:

a) Stage 1

Adherence - formal agreement on commitments and indicators, taken on by municipal PHC teams and health service managers with the Ministry of Health.

b) Stage 2

Development - carrying out of a set of actions, with the aim of promoting changes in management and care provided by the teams.

c) Stage 3

External evaluation - evaluation of access conditions and team quality.

d) Stage 4

Agreement Resetting - incorporation of new standards and quality indicators, with the aim of establishing a cyclical and systematic process based on the results achieved by participants.

The evaluations took place in 2011 (Cycle I), 2013/14 (Cycle II) and 2017/18 (Cycle III). For this study we used data collected during the external evaluation stage of Cycle II between October 2013 and March 2014, by means of interviews with FHSU professionals and Family Health team professionals. The interviews were conducted in health centers in all of Brazil’s Federative Units, using electronic equipment handled by approximately 1,000 interviewers and supervisors who had been trained beforehand by the leader institutions on using the instruments and interview techniques.

As such, information was collected on the availability of:

- spaces for carrying out FHSU activities;

- vehicles available;

- supplies;

- training;

- date of joining FHSU;

- continuing education; and

- FHSU professionals involved in Module IV (for FHSU professionals) and Module II (for interviews with PHC team professionals) of the data collection instrument.9

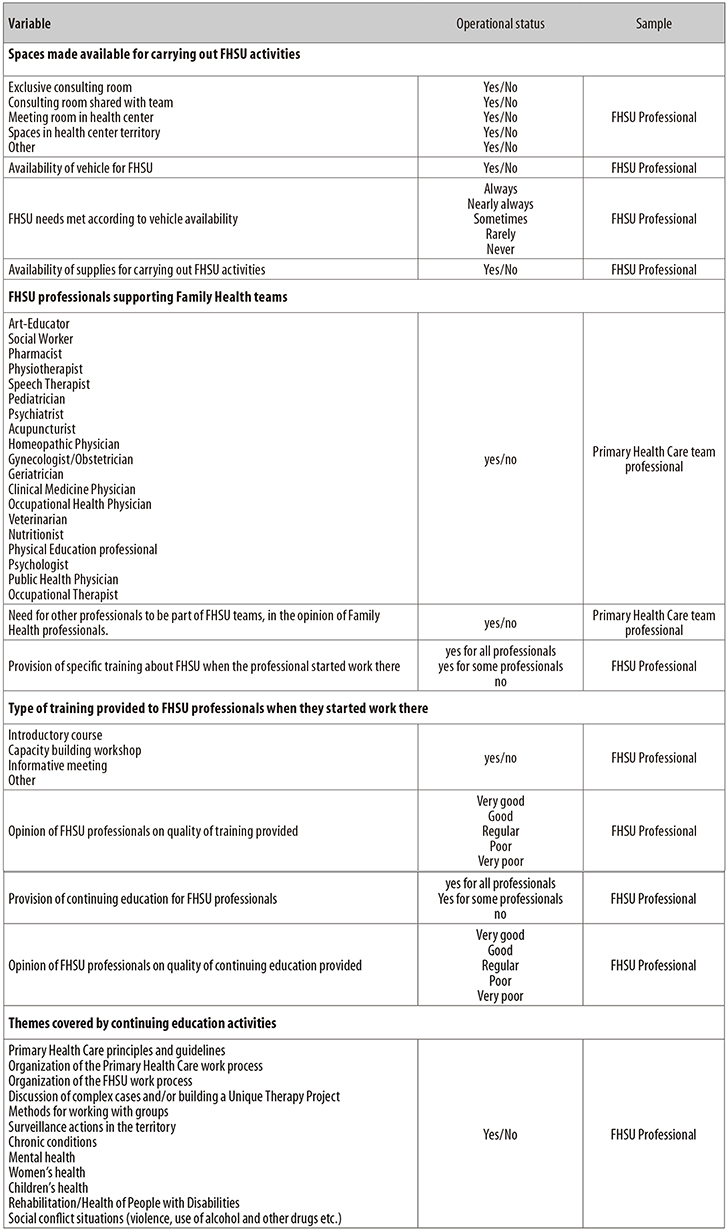

The data were tabulated and transferred to the Stata 14.0 statistical package. Descriptive analysis was performed on the variables of interest in order to obtain relative and absolute frequencies. Figure 1 shows the variables of interest and their operational status.

Figure 1 - Variables of the structure made available to Family Health Support Unit (FHSU) teas, supplies, FHSU professionals and activity operational status, based on data from the Program for Improving Access and Quality (PMAQ) national survey, Brazil, 2013

It was possible to describe the structure available for carrying out FHSU activities by asking FHSU professionals the following question,

“What spaces are available for the FHSU to carry out its activities?”

which had the following answer items: (a) Exclusive consulting room; (b) Consulting room shared with team; (c) Meeting room at the health center; (d) Spaces in the health center’s territory; (e) Others. The reply alternative for each of these items was ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

The study project was approved by the Federal University of Pelotas Faculty of Medicine Research Ethics Committee, Report No. 38/12, dated May 10th 2012. All participants signed a Free and Informed Consent form.

Results

In Brazil in 2013, 93.6% of the country’s municipalities (n=5,213) adhered to PMAQ 2, totaling 29,778 PHC teams. Of these, 17,157 (57.6%) received support from 1,773 FHSU teams to assist their actions. Above all, shared consulting rooms at primary health care centers (85.7%) and spaces in health center territories (82.7%) were found to be available for FHSU teams to carry out their activities (Table 1).

Table 1 - Description of aspects of the structure of the Family Health Support Unit (FHSU) teams based on data from the Program for Improving Access and Quality (PMAQ) national survey, Brazil, 2013

| Aspects | FHSU team work characteristics | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Spaces made available for carrying out FHSU activities (n=1,773) | ||

| Exclusive consulting room | 689 | 38.8 |

| Consulting room shared with team | 1,520 | 85.7 |

| Meeting room in health center | 1,290 | 72.7 |

| Spaces in health center territory | 1,467 | 82.7 |

| Other | 636 | 35.8 |

| Availability of vehicle for FHSU (n=1,773) | ||

| Yes | 1,333 | 75.2 |

| FHSU needs met according to vehicle availability (n=1,333) | ||

| Always | 540 | 40.6 |

| Nearly always | 527 | 39.5 |

| Sometimes | 211 | 15.8 |

| Rarely | 52 | 3.9 |

| Never | 3 | 0.2 |

| Availability of supplies for carrying out FHSU activities (n=1,773) | ||

| Yes | 1,471 | 83.0 |

Among the FHSU teams, 75.2% had a vehicle for carrying out their activities and 80.0% of the teams considered that having a vehicle available to transport them met their need always or nearly always. 83.0% of the teams reported having supplies available for them to carry out their activities (Table 1).

Specific training was offered to 63.4% of professionals when they began working at their FHSU, mainly in the form of an informative meeting (62.1%) and a capacity building workshop (61.8%). Among professionals who received some type of training, 86.9% rated its quality as good or very good (Table 2).

Table 2 - Description of variables related to training of Family Health Support Unit (FHSU) professionals based on data from the Program for Improving Access and Quality (PMAQ) national survey, Brazil, 2013

| Variables | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of specific training about FHSU when the professional started work there (n=1,773) | ||||

| Yes for all professionals | 808 | 45.6 | ||

| Yes for some professionals | 315 | 17.8 | ||

| No | 650 | 36.6 | ||

| Type of training provided to FHSU professionals when they started work there (n=1,123) | ||||

| Introductory course | 549 | 48.9 | ||

| Capacity building workshop | 694 | 61.8 | ||

| Informative meeting | 697 | 62.1 | ||

| Other | 189 | 16.8 | ||

| Opinion of FHSU professionals on quality of training provided (n=1,123) | ||||

| Very good | 302 | 26.9 | ||

| Good | 674 | 60.0 | ||

| Regular | 134 | 11.9 | ||

| Poor | 13 | 1.2 | ||

| Provision of continuing education for FHSU professionals (n=1,773) | ||||

| Yes for all professionals | 915 | 51.6 | ||

| Yes for some professionals | 280 | 15.8 | ||

| No | 578 | 32.6 | ||

| Opinion of FHSU professionals on quality of continuing education provided (n=1,195) | ||||

| Very good | 303 | 25.4 | ||

| Good | 734 | 61.4 | ||

| Regular | 141 | 11.8 | ||

| Poor | 15 | 1.2 | ||

| Very poor | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Themes covered by continuing education activities (n=1,195) | ||||

| Primary Health Care principles and guidelines | 860 | 72.0 | ||

| Organization of the Primary Health Care work process | 841 | 70.4 | ||

| Organization of the FHSU work process | 949 | 79.4 | ||

| Discussion of complex cases and/or building a Unique Therapy Project | 800 | 66.9 | ||

| Methods for working with groups | 731 | 61.2 | ||

| Surveillance actions in the territory | 636 | 53.2 | ||

| Chronic conditions | 827 | 69.2 | ||

| Mental health | 896 | 75.0 | ||

| Women’s health | 789 | 66.0 | ||

| Children’s health | 798 | 66.8 | ||

| Rehabilitation/Health of People with Disabilities | 758 | 63.4 | ||

| Social conflict situations (violence, use of alcohol and other drugs etc.) | 909 | 76.0 | ||

Continuing education was provided to 67.4% of FHSU professionals (some or all of them). Among those who took part in continuous education, 86.8% classified its quality as being good or very good. The main themes covered were: FHSU work process organization (79.4%), social conflict situations (76,0%) and mental health (75,0%) (Table 2).

The primary health care center teams received support mainly from FHSU team physiotherapists (87.4%), Physical Education professionals (87.0%) and veterinarians (85.0%) (Table 3). Moreover, 85.1% (n=14.605) of primary health care team professionals considered that the FHSUs needed to have additional professional categories.

Table 3 - Percentage of Primary Health Care (PHC) teams supported by Family Health Support Unit (FHSU) professionals based on data from the Program for Improving Access and Quality (PMAQ) national survey, Brazil, 2013

| FHSU professionals supporting PHC teams (n=17,157) | PHC teams supported by FHSU professionals | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Physiotherapi st | 14,993 | 87.4 |

| Physical Education professional | 14,931 | 87.0 |

| Veterinarian | 14,580 | 85.0 |

| Social Worker | 11,850 | 69.0 |

| Nutritionist | 10,665 | 62.2 |

| Pharmacist | 7,012 | 40.19 |

| Public Health Physician | 4,248 | 24.7 |

| Pediatrician | 3,017 | 17.6 |

| Gynecologist | 2,850 | 16.6 |

| Art-Educator | 1,022 | 6.0 |

| Occupational Therapist | 882 | 5.1 |

| Psychologist | 636 | 3.7 |

| Geriatrician | 519 | 3.0 |

| Obstetrician | 414 | 2.4 |

| Occupational Health Physician | 326 | 1.9 |

| Acupuncturist | 285 | 1.7 |

| Clinical Medicine Physician | 229 | 1.3 |

| Homeopathic Physician | 174 | 1.0 |

Discussion

The main spaces made available for carrying out FSU team activities were shared consulting rooms at primary health care centers and spaces in health center territories. Most teams had a vehicle available for their actions. The majority also reported having sufficient supplies to carry out their work.

The reality found based on these results was in accordance with FHSU guidelines.2 According to Ministry of Health recommendations, FHSU teams do not need to have their own facilities for carrying out their activities and should use spaces at the primary health care units to which they are attached or other spaces available in the health center territory, such as fitness centers, schools, parks etc.2

The availability of spaces for FHSU teams to carry out their activities appears to be reasonable. Moreover, the professionals considered the availability of a vehicle to be sufficient most of the time (39.5%) or always (40.5%). These results corroborate a previous study conducted using PMAQ Cycle II data, which concluded that infrastructure aspects were adequate for the work of the FHSU teams.10

According to Donabedian, good structure conditions represent a favorable situation for a good work process, increase the likelihood of positive outcomes and, therefore, greater service ability to provide solutions to health problems.6 As such, having knowledge of service characteristics is fundamental for health system planning.

With regard to health professional training, we believe that FHSU had not been included as a theme in Health degree curricula because it was a relatively new program created in 2008. In the opinion of students of a postgraduate specialization course in Primary Family Health Care (n=15), there are limitations in the initial training of professionals for working in PHC, which could be overcome by restructuring the curriculum, greater closeness to reality by means of internships, ensuring the theme cross cuts curriculum topics and disciplines integrated with other areas of interest to Health, such as Physical Education.11

The development of further training situations (courses, lectures, workshops etc.) is relevant for professionals working in FHSU teams. However, just over 30% of these professionals reported not having received any kind of specific training when they began working at their FHSU (36.6%), or continuing education during their job (32.6%). This data indicates the need to increase the availability of capacity building actions for FHSU teams. PMAQ results reported by Bocardo et al. also indicated the importance of greater development of initial training and continuing education in the context of the work of FHSU professionals.10

Continuing education is equally important in view of the challenges faced by professionals in their actions, such as multiprofessional work, difficulties in creating and developing joint, intersectoral and integrated actions, so as to incorporate service user participation.12 Results of a qualitative study involving FHSU professionals working in municipalities in Bahia state revealed that educational activities aimed at them were too scarce and insufficient to transform working practices.13

The main themes covered by the continuing education activities provided to FHSU professionals were organization of the FHSU work process, social conflict situations and mental health. It appears to be coherent that these are the most frequent subjects, as it is fundamental for professionals to know the principles of the work process in their field of action. Social conflict situations, such as violence and use of alcohol and drugs, are frequent and PHC professionals need to be able to deal with them in their contact with the population.14 In Brazil, whereas violence was the seventh leading cause of premature death in 1990, it was the main cause in 2005 and came in second place in 2015.14

Furthermore, the FHSU guidelines provide for prioritizing mental health professionals and actions, given the significant level of epidemiological data on mental disorders cared for by the Family Health service,2 with prevalence of up to 50% among primary health care center users.15

The choice of professionals who comprise the FHSU teams is made by municipal health service managers, in accordance with priorities based on analysis of the epidemiological data, the needs of the territory and the needs of the Primary Health teams to be supported by FHSU.2 The actions of the FHSU teams must be aimed at prevention, health promotion, protection and rehabilitation, within the context of the social determinants of a population or an individual.2

The FHSU professionals who most provided support to PHC teams were physiotherapists (87.4%) and Physical Education professionals (87%), who were taken to be most prevalent because of their work with chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCD). CNCDs are known to be the main component of Brazil’s disease burden, hence why working with them has gained priority status in health services.16 There is evidence that physical activity can both prevent CNCDs from appearing17 and also help to treat them1.8 In view of this, health promotion strategies focused on levels of physical activity have been implemented.19

Veterinarians working in PHC are responsible for observing and contributing to aspects related to human/animal integration.20 Among the PHC professionals taking part in PMAQ, 85% reported counting on the support of FHSU veterinarians.

According the Federal Council of Veterinary Medicine, the actions of veterinarians working in FHSUs include (a) evaluation of health risk factors, (b) prevention, control and diagnosis of diseases transmitted by animals, (c) health education focusing on preventing anthropozoonoses, (d) Public Health studies and research with emphasis on territoriality and quality of care, among others.21 The high participation of veterinarians in FHSUs is attributed to factors that collaborate with disease dissemination, such as close contact with pet animals, which increases risk of exposure to zoonoses.20 According to data produced by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the National Health Survey conducted in 2013 revealed that 44.3% of Brazilian households had at least one dog, 17.7% had at least one cat and that Brazil had a total of 52.2 million dogs and 22.1 million cats.22

Notwithstanding, according to a literature review conducted in 2017 on publications about FHSUs, no health study on the theme of the human/animal relationship was found.23 It is important for the work of veterinarians to be explored more by scientific literature in order to consolidate and disseminate knowledge about the role of these professionals in FHSUs.

The limitations of this study include the condition of the teams who answered the PMAQ evaluation questionnaire. They were designated by the municipalities and this may have been because their work performance was better than that of those who were not indicated. As such judicious interpretation of the results presented is recommended.

Another important point is the study’s national coverage. Moreover, it is a quantitative study on the work of FHSU teams, whereas the majority of studies on FHSUs are qualitative.23 The data presented can contribute in a relevant manner to public health policy planning and evaluation.

In view of the lack of a criterion that establishes a parameter for evaluating team structure, classifying them as adequate or inadequate, the results found suggest that the FHSU teams are structured in accordance with the recommendations of the FHSU guidelines: inexistence of an exclusive space;2 – of them having a vehicle available when carrying out their activities.

The need stands out to increase to increase the scope of further training actions for FHSU professionals, given the high percentage of these professionals to whom no specific training or continuing education was offered in relation to the work they do.

With regard to Family Health Support Unit professionals who provide support to Primary Health Care teams, a wide diversity of professions was found, with physiotherapists, Physical Education professionals and veterinarians being the most prevalent. We suggest that further studies be conducted with the aim of verifying whether these professionals meet the needs of the territories in which the teams they support work.

REFERENCES

1. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Departamento de Atenção Básica. Secretaria de Políticas de Saúde. Programa Saúde da Família. Rev Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2000 jun [citado 2019 set 10];34(3):316-9. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v34n3/2237.pdf . doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102000000300018 [ Links ]

2. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Diretrizes do NASF: núcleo de apoio a saúde da família [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2010 [citado 2019 set 10]. 152 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/publicacoes/cadernos_ab/abcad27.pdf [ Links ]

3. Reis EJFB, Santos FP, Campos FE, Acúrcio FA, Leite MTT, Cherchiglia ML et al. Avaliação da qualidade dos serviços de saúde: notas bibliográficas. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 1990 jan-mar [citado 2019 set 10];6(1):50-61. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v6n1/v6n1a06.pdf . doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X1990000100006 [ Links ]

4. Donabedian A. The quality of medical care. Science [Internet]. 1978 May [cited 2019 Sep 10];200(4344):856-64. Available from: Available from: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/200/4344/856.long . doi: 10.1126/science.417400 [ Links ]

5. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Programa nacional de melhoria do acesso e da qualidade da atenção básica (PMAQ) [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2011 [citado 2019 set 10]. 44 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.saude.mt.gov.br/arquivo/3183 [ Links ]

6. Donabedian A. The quality of care how can it be assessed? JAMA [Internet]. 1988 Sep [cited 2019 Sep 10];260(12):1743-8. Available from: Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/374139 . doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033 [ Links ]

7. Donabedian A. Prioridades para el progresso en la evaluación y monitoreo de la calidad de la atención. Salud Pública Mex [Internet]. 1993 jan [citado 2019 set 10];35(1):94-7. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://saludpublica.mx/index.php/spm/article/view/5636/6132 [ Links ]

8. Silva ATC, Aguiar ME de, Winck K, Rodrigues KGW, Sato ME, Grisi SJFE, et al. Núcleos de apoio à saúde da família: desafios e potencialidades na visão dos profissionais da atenção primária do município de São Paulo, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2012 nov [citado 2019 set 10];28(11):2076-84. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v28n11/07.pdf . doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2012001100007 [ Links ]

9. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Departamento de Atenção Básica. Nota metodológica - PMAQ ciclo 2 [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2014 [citado 2019 set 10]. 111 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dab.saude.gov.br/portaldab/ape_pmaq.php?conteudo=2_ciclo [ Links ]

10. Bocardo D, Andrade CLT, Fausto MCR, Lima SML. Núcleo de apoio à saúde da família (Nasf): panorama nacional a partir de dados do PMAQ. Saúde Debate [Internet]. 2018 set [citado 2019 set 10];42(spe 1):130-44. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/sdeb/v42nspe1/0103-1104-sdeb-42-spe01-0130.pdf . doi: 10.1590/0103-11042018s109 [ Links ]

11. Falci DM, Belisário SA. A inserção do profissional de educação física na atenção primária à saúde e os desafios em sua formação. Interface [Internet]. 2013 out-dez [citado 2019 set 10];17(47):885-99. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/icse/v17n47/aop3913.pdf . doi: 10.1590/S1414-32832013005000027 [ Links ]

12. Anjos KF, Meira SS, Ferraz CEO, Vilela ABA, Boery RNSO, Sena ELS. Prospects and challenges of core support for family health as to practice in health. Saúde Debate [Internet]. 2013 out-dez [citado 2019 set 10];37(99):672-80. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/sdeb/v37n99/a15v37n99.pdf . doi: 10.1590/S0103-11042013000400015 [ Links ]

13. Bispo Júnior JP, Moreira DC. Educação permanente e apoio matricial: formação, vivências e práticas dos profissionais dos núcleos de apoio à saúde da família e das equipes apoiadas. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2017 [citado 2019 set 10];33(9):e00108116. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v33n9/1678-4464-csp-33-09-e00108116.pdf . doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00108116 [ Links ]

14. França EB, Passos VMA, Malta DC, Duncan BB, Ribeiro ALP, Guimarães MDC, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 249 causes in Brazil and states during 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Popul Health Metr [Internet]. 2017 Nov [cited 2019 Sep 10];15(1):39. Available from: Available from: https://pophealthmetrics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12963-017- 0156-y . doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0156-y [ Links ]

15. Gomes VF, Miguel TLB, Miasso AI. Transtornos mentais comuns: perfil sociodemográfico e farmacoterapêutico. Rev Latino-Am Enferm [Internet]. 2013 nov-dez [citado 2019 set 10];21(6):9. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v21n6/pt_0104-1169-rlae-0104-1169-2990-2355.pdf . doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.2990.2355 [ Links ]

16. Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Silva GA, Menezes AM, Monteiro CA, Barreto SM, et al. Doenças crônicas não transmissíveis no Brasil: carga e desafios atuais. Lancet [Internet]. 2011 maio [citado 2019 set 10];61-74. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.thelancet.com/pb/assets/raw/Lancet//pdfs/brazil/brazilpor4.pdf . doi: 10.1016/S0140- 6736(11)60135-9 [ Links ]

17. Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet [Internet]. 2012 Jul [cited 2019 Sep 10];380(9838):219-29. Available from: Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61031-9/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 [ Links ]

18. Piccini RX, Facchini LA, Tomasi E, Siqueira FV, Silveria DS, Thumé E, et al. Promoção, prevenção e cuidado da hipertensão arterial no Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2012 jun [citado 2019 set 10];46(3):543-50. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v46n3/3208.pdf . doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102012005000027 [ Links ]

19. Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, Andersen LB, Owen N, Goenka S, et al. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet [Internet]. 2012 Jul [cited 2019 Sep 10];380(9838):272-81. Available from: Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)60816-2/fulltext . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60816-2 [ Links ]

20. Xavier DR, Nascimento GNL. O médico veterinário na atenção básica à saúde. Rev Desafios [Internet]. 2017 [citado 2019 set 10];4(2):28-34. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://sistemas.uft.edu.br/periodicos/index.php/desafios/article/download/3199/9646/ . doi: 10.20873/uft.2359-3652.2017v4n2p28 [ Links ]

21. Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária. Portal do Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária - médico veterinário no NASF [Internet]. Brasília: Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária; 2017 [citado 2017 dez 14]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.cfmv.gov.br/portal/pagina/index/id/93/secao/2 [ Links ]

22. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Pesquisa nacional de saúde - PNS 2013 [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2015 [citado 2017 dez 19]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/10138-pns-2013-tres-em-cada-quatro-brasileiros-costumam-buscar-atendimento-medico-na-rede-publica-de-saude.html [ Links ]

23. Seus TL, Freitas MP, Siqueira FV. Publications scenario about family health support centers. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde [Internet]. 2017 May [cited 2019 Sep 10];22(5):429-38. Available from: Available from: http://rbafs.org.br/RBAFS/article/view/12103 . doi: 10.12820/rbafs.v.22n5p429-438 [ Links ]

*Article derived from the Ph.D. dissertation entitled ‘Family Health Support Units and Physical Education professionals’, defended by Thamires Lorenzet Seus at the Federal University of Pelotas Physical Education Postgraduate Program in 2018. Research funded by the Ministry of Health / Health Actions Secretariat / Primary Health Care Department: Process No. 25000.187078/2011-11.

Received: February 08, 2019; Accepted: September 10, 2019

texto em

texto em

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI