Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.29 no.1 Brasília 2020 Epub 28-Fev-2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742020000100011

OPINION ARTICLE

The World Health Organization's SAFER initiative and the challenges in Brazil to reducing harmful consumption of alcoholic beverages

1Pan Americana Health Organization (PAHO)/World Health Organization (WHO), Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health Department, Washington DC, USA

Alcohol (or ethanol) is a psychoactive substance that causes intoxication. It is toxic to the cells and tissues of several of the body’s organs; it is carcinogenic, teratogenic, immunosuppressive, and its repeated use leads to tolerance and can cause chemical dependency. It is responsible for over 230 distinct health conditions, according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10).1,2

Harmful use of alcoholic beverages is responsible for 7.2% of the global disease burden among males and 2.2% among females. Alcohol consumption causes some 3 million deaths worldwide every year, as well as millions of years of life lost due to early deaths and years lived with disability or sequelae of non-fatal injury or other chronic diseases. Among people aged 15-49 years old, alcohol is responsible for 10% of all deaths worldwide and is the most important risk factor.3

Total volume of alcohol consumed, context of consumption, frequency and amount consumed each time increase the risk of acute and chronic health and social problems. Dose-dependent risk increases with consumption volume and frequency, as well as increasing exponentially in relation to the amount consumed on a single occasion.4

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers that any amount of alcohol is associated with some degree of risk to health, such as is the case, for example, of breast cancer and dependency or injury. In all countries throughout the world, alcohol consumption has a negative impact on public health.1

Vulnerable populations and populations living in middle- or low-income countries have higher relative alcohol-related death and hospitalization rates, in comparison to more affluent populations, despite consuming less or the same amount of alcohol. As such, groups characterized by poorer socio-economic conditions suffer disproportionately more. Other risk factors are also involved, such as unhealthy diets, tobacco smoking, as well less access to information, education, security and health services.5

WHO’s SAFER Initiative

In view of the global impact of alcohol consumption, in 2010 the World Health Assembly adopted, by consensus, the Global strategy for reducing harmful use of alcohol, with ten areas for policy action based on the most up to date and robust scientific evidence.6 Other subsequent global instruments - such as the Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) -7,8,9 have joined the global strategy to promote the same policy measures, with the aim of reducing harmful consumption of alcohol. Notwithstanding, little progress has been documented, and the commitments taken on globally will not be achieved if immediate action is not taken.10 The main obstacles identified to implementing effective polices are the influence and interference of the alcoholic beverages industry and organizations funded by or related to it.11

In an attempt to overturn this panorama, in September 2018, WHO launched the SAFER initiative, during the Third United Nations High-Level Conference on Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Control, in collaboration with a variety of international intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations.12

The objective of the initiative is to foment and strengthen national and subnational actions in order to reduce harmful consumption of alcohol, promoting the implementation of the global strategy, centered on a package of interventions in five strategic areas, based on evidence of their impact on public health and their cost-benefit. In addition, the SAFER initiative acknowledges the need to protect the public policy formulation process from the interference of the alcohol industry, as well as emphasizing the importance of a health surveillance system and sustainable monitoring that ensures accountability in terms of progress, not only with regard to implementation of measures, but also in relation to their impact on reducing harmful use of alcohol.

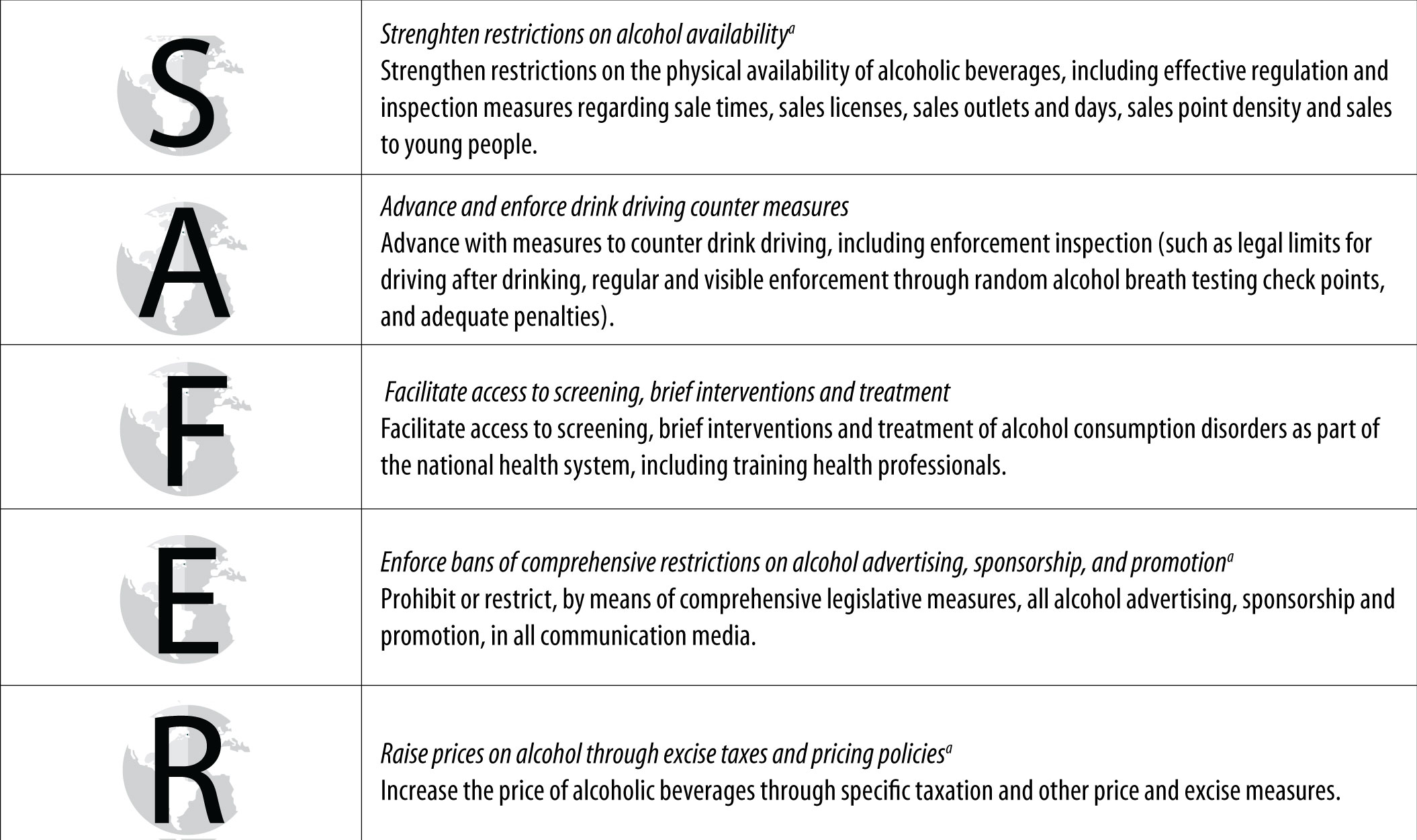

SAFER is an acronym that stands for the five policy action areas, as shown in Figure 1.

a) Measures considered to be most cost-effective by WHO.

Figure 1 - SAFER initiative policy action areas

Each country or jurisdiction should implement these measures, monitor their enforcement and protect public health from the interests of the alcoholic beverages industry (right from production, through to distribution, sales and advertising).

The SAFER initiative is directed towards government decision makers responsible for developing the national or subnational policy, as well as action plans to reduce harm caused by alcohol consumption. Given that such harm dos not relate exclusively to health, but also involves social and economic harm, and that several of the necessary governmental measures fall outside the health sector, the initiative also serves for other sectors and for articulating an integrated and coherent response that is internally consistent with the target of improving public health.13,14

Challenges in Brazil

The SAFER initiative was officially presented to national authorities at an event organized by the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in October 2019. Brazil was the first country in the Region of the Americas to discuss the initiative on a national level. The event was attended by politicians, ministries, civil society organizations and universities, national and international experts. They discussed the national situation of alcohol consumption and harm caused by it, existing policies in response to the problem, as well as several successful international experiences. This was the first step for the future official adoption of the initiative. Assuming that the initiative will be adopted in Brazil, there are certain challenges to be faced.

To start with, the country needs to take on the political commitment at the highest level, so that harmful alcohol use is considered to be a public health priority, recognizing its huge impact, due to its health, social and economic costs. Several of the policies needed to reduce the problem do not depend on the health sector and, without coordinated and coherent intersectoral action, these policies will not be feasible. The taxes raised from alcohol sales are not sufficient to cover the majority of public expenditure on paying for direct and indirect social and health costs arising from alcohol consumption, including loss of productivity, absenteeism, damage to public and private property, as well as harm to third parties victims of alcohol consumption even though they do not drink.

In other words, the health of the Brazilian population needs to be placed above commercial interests, as a right of all citizens, whether or not they consume alcoholic beverages. In this way, it will be possible to protect underage people from exposure to marketing and from pressure to start and increase alcohol consumption; from access to very cheap drinks sold to people under 18 years old; and from the impact of alcohol consumption by parents, family members, friends or other people. Former drinkers can be protected from mass pressure to start drinking again through widespread and little regulated alcohol advertising and promotion in Brazil.

Taking on this commitment requires leadership for the development of a comprehensive policy, centered on the most cost-effective measures and use of national and international information for decision making and formulation of appropriate legislative measures, including allocation of the human and financial resources needed for such activities. In order for the necessary legislative measures to be adopted, the influence and interference of the alcoholic beverages industry need to be avoided. At the moment, thousands of local, regional, national, university, school, sports, cultural and political events, among others, are organized using industry funding and sponsorship. This influence not only hampers the adoption of regulatory measures, but also contributes to forming public opinion with a distorted vision of the harm and benefits of alcohol consumption, the role of alcohol in Brazilian culture, the role of the industry in the economy, the role of exposure to advertising in starting and increasing alcohol intake among young people, and the role played by alcohol in a large number of diseases - including cancer. All of this compromises the effectiveness of regulatory measures to control harmful alcohol consumption and related harm.

The objective of the SAFER initiative is to reduce harm resulting from alcohol consumption, but not to promote prohibition of its intake or sales. At the same time, it recognizes that alcohol is a psychoactive and addictive substance that is highly toxic for the human body and, in the same way as other products that cause harm to health, to those who consume them and to other people, it needs to be strictly regulated. The regulatory panorama in Brazil is still very weak, with out of date and incomplete legislation. The taxation policy is not aimed at improving health and results in very low prices. Unlike many other countries, Brazil has no specific licensing system for the sale of alcoholic beverages that can be regulated and enforced. There is little regulation of advertising, and this enables new products to be launched on the market for mass consumption, at prices that are very affordable and attractive for young people. Unregulated sales via internet and household delivery also offer greater access to this group, given that there is no effective control over age.

Social acceptance of alcohol consumption is very high, probably because of unregulated far-reaching and mass advertising, promotion and sponsoring. Sales to underage people do not result in effective punishment of retailers who break the law (on this issue, we recall that sale times have been controlled in some municipalities, with positive results and with the population’s support). Sales point density is not regulated, nor is consumption in public places. Well-known practices, such as “open bar”, with drinks sold below cost price, are rarely prohibited. Regulation of alcoholic beverage advertising, sponsoring and promotion is another challenge. Beer and most forms of wine are excluded from the law on advertising regulation, and sponsoring of any kind of alcoholic drink is neither regulated nor restricted, exposing young children to brands of drinks which they will later seek to consume, at an early age and in quantities that put adolescents’ health and brain development at risk.

Progress has been made with legislation on drink driving, but enforcement continues to be precarious and only exists in a few cities; the initial success of the “Dry Law”, with reduction in traffic accident mortality, has recoiled, although in some cities continuing efforts still produce positive results. Finally, in primary health care and care services for alcohol and drug users, screening, brief interventions and treatment of dependency continue to be one-off and insufficient to meet demand.

There is still much to be done at the municipal, state and national levels in Brazil. Once there is political will and a comprehensive vision of public health, the country will be able to bring together the conditions needed to overcome the current situation and avoid many deaths and health conditions, ensuring a healthy future for the new generations, who today are born and grow up surrounded by incentives to start drinking early, increase consumption and to believe that alcohol is necessary for a healthy life. When harm appears, the blame is placed on individual maladjustments, character problems, “bad friends”, or parents, and never on the permissive and little regulated environment in which our young people are born, grow up, are educated, live and amuse themselves. All of us, both government and population, are paying the price of alcohol consumption, while alcoholic beverage production, distribution, sales and marketing companies are being benefited by huge profits but do not pay for the externalities of their businesses. Implementation of the SAFER package can be the way forward to achieving a better balance between these factors, bringing benefits for the population’s health and for national development.

Referências

1. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. Available from: Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/ [ Links ]

2. Rehm J, Gmel GE, Gmel G, Hasan OS, Imtiaz S, Popova S et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease-an update. Addiction [Internet]. 2017 Jun [cited 2020 Jan 29];112(6):968-1001. Available from: Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/add.13757 . doi: 10.1111/add.13757 [ Links ]

3. GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet [Internet]. 2018 Aug [cited 2020 Jan 29];392(10152):1015-35. Available from: Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31310-2/fulltext . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2 [ Links ]

4. Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Sempos CT. The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: an overview. Addiction [Internet]. 2003 Sep [cited 2020 Jan 29];98(9):1209-28. Available from: Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00467.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed . doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00467.x [ Links ]

5. Grittner U, Kuntsche S, Graham K, Bloomfield K. Social inequalities and gender differences in the experience of alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Alcohol [Internet]. 2012 Sep-Oct [cited 2020 Jan 29];47(5):597-605. Available from: Available from: https://academic.oup.com/alcalc/article/47/5/597/98601 . doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags040 [ Links ]

6. World Health Organization. Global strategy for reducing harmful use of alcohol [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization ; 2010 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. Available from: Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/gsrhua/en/ [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization ; 2013 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. 103 p. Available from: Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

8. United Nations. Political declaration of the third high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases [Internet]. [New York]: United Nation; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. Available from: Available from: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/73/2 [ Links ]

9. United Nations. Sustainable development goals: 17 goals to transform our world [Internet]. New York: United Nation; 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. Available from: Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs [ Links ]

10. Manthey J, Shield KD, Rylett M, Hasan OSM, Probst C, Rehm J. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and2017 and forecasts until 2030: a modelling study. Lancet [Internet]. 2019 May [cited 2020 Jan 29];393(10190):2493-502. Available from: Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32744-2/fulltext . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32744-2 [ Links ]

11. Babor TF, Robaina K, Brown K, Noel J, Cremonte M, Pantani D, et al. Is the alcohol industry doing well by “doing good”? Findings from a content analysis of the alcohol industry’s actions to reduce harmful drinking. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 29];8:e024325. Available from: Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/10/e024325.full.pdf . doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024325 [ Links ]

12. World Health Organization. WHO launching SAFER, a new alcohol control initiative [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization ; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. Available from: Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/safer/en/ [ Links ]

13. Rekve D, Banatvala N, Karpati A, Tarlton D, Westerman L, Sperkova K, et al. Prioritizing alcohol action for health and development. BMJ [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2020 Jan 29];367:l6162. Available from: https://movendi.ngo/reports/prioritising-action-on-alcohol-for-health-and-development/. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6162 [ Links ]

14. World Health Organization. (2019) The technical package SAFER: a world free from alcohol related harms [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization ; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. 24 p. Available from: Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330053/9789241516419-eng.pdf [ Links ]

texto em

texto em