Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 1679-4974versão On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.29 no.2 Brasília 2020 Epub 31-Mar-2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742020000200008

Opinion Article

Assessing the severity of COVID-19

1Faculdade de Medicina São Leopoldo Mandic, Campinas, SP, Brazil

2Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Departamento de Saúde Coletiva, Campinas, SP, Brazil

Ever since the beginning of the current outbreak of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which causes COVID-19, there has been great concern in the face of a disease that has spread rapidly in several regions of the world, with different impacts. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), on March 18th 2020 there were more than 214,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases globally. There were no strategic plans ready to be applied to a coronavirus epidemic - it is all new. Recommendations made by WHO,1 the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (United States CDC)2 and other national and international organizations have suggested that influenza contingencies plans and their tools should be applied because of the clinical and epidemiological similarities between these respiratory viruses. These contingency plans provide for different actions according to pandemic severity.

The fourth update of the Pandemic Influenza Plan - PIP, prepared by the United States Department of Health and Human Services3 and published in 2017, included measures for different government and civil society areas. In addition, in order for the response to be proportional to the severity of the situation, it uses the Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework - PSAF4 as a risk assessment tool.

The PSAF proposes two assessment dimensions.4 For the transmissibility dimension, the score ranges from 1 to 5, and the indicators are: symptomatic attack rate in different scenarios; R0 (basic reproductive number); and peak percentage outpatient visits for influenza-like illness. In turn, for the clinical severity dimension, the score ranges from 1 to 7, and the variables used are: case fatality rate; case-hospitalization ratio (proportion of hospitalization); and deaths-hospitalization ratio, considering only influenza cases, in the current COVID-19 situation. This framework, however, uses data that can be obtained at the onset of the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, differently from its application in influenza epidemics, when the attack and fatality rates are used, these being population-based indicators and, therefore, hard to get from reliable databases at the start of any epidemic.

By using the PSAF, assessments can be done with available data at any time and can be increasingly refined as the pandemic progresses. As we are at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic, several clinical and epidemiological aspects of this disease are still not clear; nevertheless, a large number of peer-reviewed articles have been published recently in specialized periodicals. As such, for this assessment, we used data from a recent publication about 44,415 COVID-19 cases that occurred in China with effect from January 11th 2020.5

As many seriously ill cases were still hospitalized at the time the articles were written, when calculating the proportion of hospitalization we only used cases for which the disease had had an outcome (recoveries, hospital discharge and deaths).6 In order to refine the results, each of the periods of the epidemic in China was assessed separately. It is known that fatality can be affected by factors such as knowledge about the disease, existing diagnosis capacity and hospital overcrowding. In addition, more recent cases may still be hospitalized, without it being possible to know the outcome.

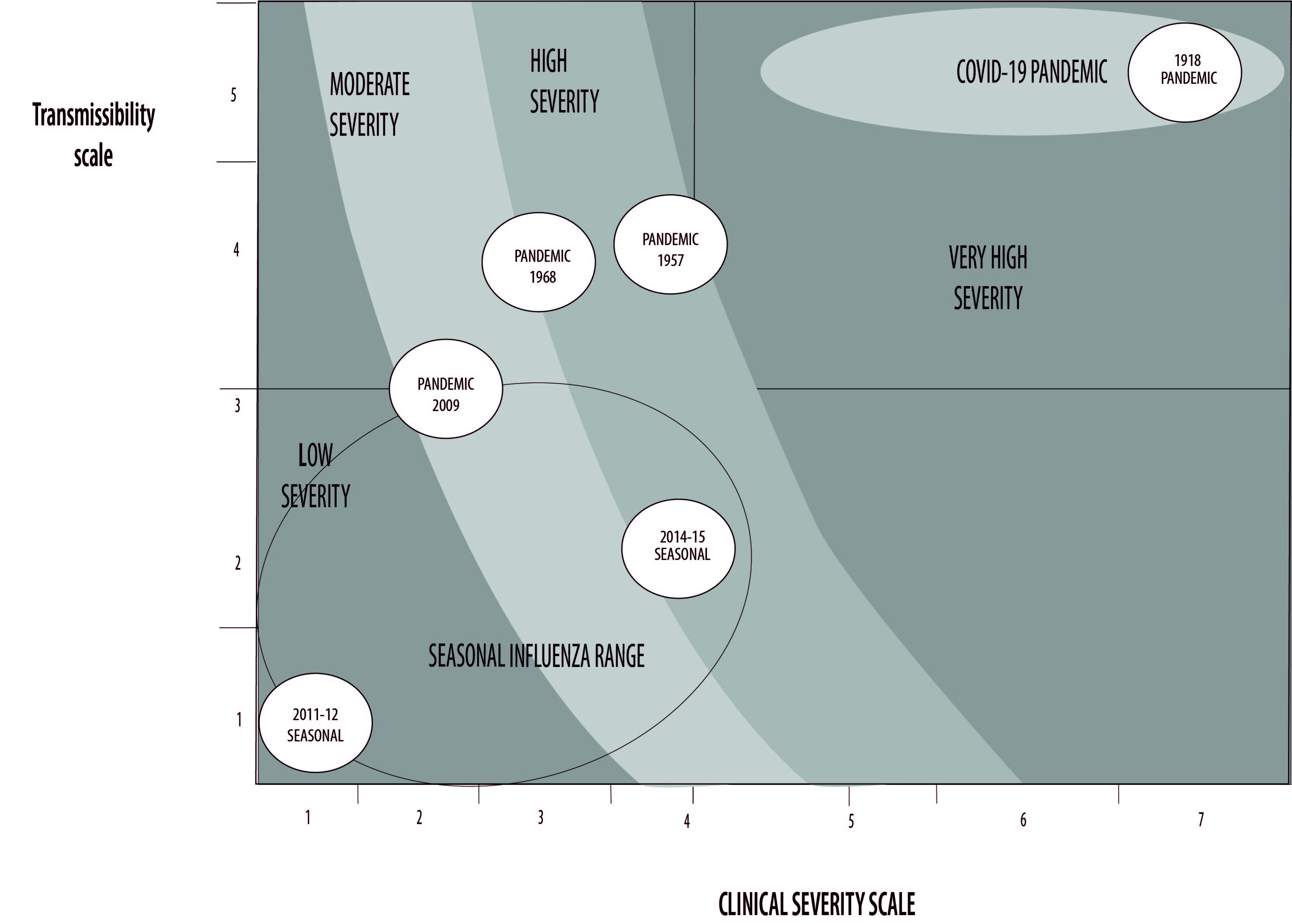

Applying PSAF indicators (Table 1 and Figure 1) shows a highly transmissible disease,1,7,8 and the clinical severity indicators also suggest high severity.9-11 Although it contains slight discrepancies in the clinical severity dimension, which is to be expected in non-randomized observational studies, the COVID-19 epidemic, assessed according to the PSAF using Chinese data, can be compared with severe historical epidemics, such as the 1918 influenza epidemic. Based on this initial assessment (Figure 1), COVID-19 appears as a disease with high transmissibility and high clinical severity, as revealed by the fatality seen in other countries where the epidemic is in the initial stage.1

Table 1 - COVID-19 pandemic transmissibility and severity indicators using the Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework - PSAF and Chinese case data up to February 11th 2020

| Transmissibility | Population | Results% (95%CI) | Escore* | ||

| Secondary case attack rate in family outbreaks | China7 | 22.0 | 5 | ||

| R0 (basic reproductive number) | China(8 | 2.2 (95%CI 1.4; 3.9) | 5 | ||

| China1 | 2.0; 2.5 | 5 | |||

| Clinical severity | Population | Period | deaths/ confirmed cases | Results% (95%CI) | Score* |

| Fatality | Up to 11/Feb/2020 | ||||

| China (general population)5 | Prior to 31/Dec/2019 | 15/104 | 14.4 (7.7; 21.2) | 7 | |

| 1-10/Jan/2020 | 102/653 | 15.6 (12.8; 18.4) | 7 | ||

| 11-20/Jan/2020 | 310/5,417 | 5.7 (5.1; 6.3) | 7 | ||

| 21-31/Jan/2020 | 494/26,468 | 1.9 (1.7; 2.0) | 7 | ||

| 1/Feb/2020 | 102/12,030 | 0.8 (0.7; 1.0) | 6 | ||

| China (health workers)5 | Prior to 31/Dec/2019 | -/- | - | - | |

| 1-10/Jan/2020 | 1/20 | 5.0 (0.0; 14.6) | 7 | ||

| 11-20/Jan/2020 | 1/310 | 0.3 (0.0; 1.0) | 5 | ||

| 21-31/Jan/2020 | 2/1,036 | 0.2 (0.0; 0.5) | 4 | ||

| 1/Feb/2020 | 1/322 | 0.3 (0.0; 0.9) | 5 | ||

| Clinical severity | Population | Period | deaths/ confirmed cases | Results% (95%CI) | Score* |

| As at 3/Mar/2020 | |||||

| Wuhan¹ | Entire period | 2.803/67,103 | 4.2 (4.0; 4.3) | 7 | |

| Rest of China¹ | Entire period | 112/13,071 | 0.9 (0.7; 1.0) | 6 | |

| United States² | Entire period | 6/60 | 10.0 (2.4; 17.6) | 7 | |

| Italy¹ | Entire period | 52/2,036 | 2.6 (1.9; 3.2) | 7 | |

| South Korea¹ | Entire period | 28/4,812 | 0.6 (0.4; 0.8) | 6 | |

| Japan¹ | Entire period | 6/268 | 2.2 (0.5; 4.0) | 7 | |

| Iran¹ | Entire period | 66/1,501 | 4.4 (3.4; 5.4) | 7 | |

| Population | Period | Severe+critical cases/total cases | Results% (95%CI) | Score | |

| Proportion of hospitalization (due to COVID-19) | China (health workers)5 | Entire period up to 11/Feb/2020 | 247/1,688 | 14.6 (12.9; 16.3) | 7 |

| China (general population)5 | Entire period up to 11/Feb/2020 | 8,255/44,415 | 18.6 (18.2; 18.9) | 7 | |

| Population | Period | deaths/ (cured+ discharges+ deaths) | Results (%) (95%CI) | Score | |

| Hospital mortality rate (due to COVID-19) | Jinyintan Hospital (Wuhan)9 | 1-20/Jan/2020 | 11/42 | 26.2 (12.9; 39.5) | 7 |

| Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University10 | 1-28 /Jan/2020 | 6/53 | 11.3 (2.8; 19.9) | 4 | |

| China11 | 11/Dec/2019 a 29/Jan/2020 | 15/79 | 19.0 (10.3; 27.6) | 7 |

* Severity score (1-7) using Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework indicators.4

Adapted from: Reed C, Biggerstaff M, Finelli, Koonin LM, et al, Novel framework for assessingn epidemiologic effect of influenza epidemics pandemic. Emerg infect Dis 2013;19(1):85-91

Figure 1 - Application of COVID-19 transmissibility and clinical severity scale results on the influenza effects assessment graph, with (scaled) examples of influenza pandemics and seasonal influenza outbreaks

Also noteworthy are the indictors found for health workers. Among Chinese health workers, fatality was lower than among the general population in that country (Table 1). However, with regard to incidence, the Italian Group for Evidence-based Medicine reported that 8.3% of total COVID-19 cases recorded in Italy occurred among health workers, this being double that reported in China (3.8%).12 Lack of personal and collective protective equipment in health services, in addition to the large volume of cases, has contributed to this situation. In Brazil, guidance given for symptomatic individuals (runny nose, fever and cough) to seek primary health care services may result in high incidence rates among health workers there, in view of lack of structure and personal protective equipment, as already observed by government bodies. In order to overcome this challenge, several countries have proposed the creation of specific facilities for clinical assessment of medium severity cases, thus enabling concentrated investment in equipment as well as reducing the burden on higher complexity services where more serious cases need to be attended to.

Despite the relevance of the findings, indicator heterogeneity between different regions where there is transmission needs to be taken into consideration, given that indicators vary according to actions, routines, availability of supplies, health and surveillance service structure, as well as cultural and political issues. The PSAF is a tool that was develo ed based on United States data for initial assessment of pandemic influenza and the document itself makes the proviso that successive reassessments are important, given that information is dynamic. SARS-CoV-2 is a respiratory virus that is different to the influenza virus and its behavior has not yet been totally enlightened. As such, applying these indicators in the social, political and epidemiological context of other countries may lead to results different to those expected.

This assessment of the COVID-19 epidemic needs to be modified as and when new information is added. However, the need is stressed for the scientific community and national and international epidemiological surveillance teams to take great care when monitoring the epidemic’s trends, critically assessing the tools available for understanding the situation.

Referências

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [ Links ]

2. Centers for Disesase Control and Prevention. Pandemic preparedness resources [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Centers for Disesase Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/pandemic-preparedness-resources.html [ Links ]

3. U.S. Departament of Health and Human Services. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness H. Pandemic influenza plan - update IV (December 2017). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Departament of Health and Human Services; 2017 [cited 2020 Mar 23]. 52 p. Available from: Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/pan-flu-report-2017v2.pdf [ Links ]

4. Reed C, Biggerstaff M, Finelli L, Koonin LM, Beauvais D, Uzicanin A, et al. Novel framework for assessing epidemiologic effects of influenza epidemics and pandemics. Emerg Infec Dis [Internet]. 2013 Jan [cited 2020 Mar 23];19(1):85-91. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1901.120124 [ Links ]

5. Ghani AC, Donnelly CA, Cox DR, Griffin JT, Fraser C, Lam TH, et al. Methods for estimating the case fatality ratio for a novel, emerging infectious disease. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2005 Sep [cited 2020 Mar 23];162(5):479-86. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi230 [ Links ]

6. The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) - China, 2020 [Internet]. China CDC Weekly [Internet]. 2020 Feb [cited 2020 Mar 3];2(8):113-22. Available from: Available from: http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51 [ Links ]

7. Zhonghua Liu, Xing Bing, Xue Za Zhi. An update on the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). Chin J Epidemiol. 2020 Feb [cited 2020 Mar 23];41(2):139-144. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.002 [ Links ]

8. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020 Jan [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [ Links ]

9. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Feb [cited 2020 Mar 23];395(10223):507-13. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [ Links ]

10. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 Feb [cited 2020 Mar 23];323(11):1061-9. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [ Links ]

11. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020 Feb [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [ Links ]

12. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 Feb [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Avaiable from: Avaiable from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [ Links ]

texto em

texto em