Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versión impresa ISSN 1679-4974versión On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.30 no.2 Brasília 2021 Epub 14-Abr-2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1679-49742021000200007

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Exclusive breastfeeding and introduction of ultra-processed foods in the first year of life: a cohort study in southwest Bahia, Brazil, 2018*

1Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Vitória da Conquista, BA, Brazil

4²Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Departamento de Nutrição, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil

Objective:

To analyze association between exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and the introduction of ultra-processed foods in children under 12 months old.

Methods:

This was a Cohort study, conducted with children in Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, Brazil. The main exposure was EBF (days: <120; 120-179; ≥180). The outcome variable was the introduction of four or more types of ultra-processed foods in the first year of life. Poisson regression analysis was used.

Results:

286 children were evaluated, of whom 40.2% received four or more ultra-processed foods and 48.9% EBF for less than 120 days. EBF for less than 120 days (RR=2.94 - 95%CI 1.51;5.71) and for 120-179 days (RR=2.17 - 95%CI 1.09;4.30) was associated with the outcome after adjustment by socioeconomic, maternal, paternal and child variables.

Conclusion:

EBF for less than 180 days increased the risk of introducing four or more ultra-processed foods in the first year of life.

Keywords: Breastfeeding; Infant Nutrition; Industrialized Foods; Longitudinal Studies.

Introduction

Use of ultra-processed foods has been increasing over the years in the homes of Brazilian families.1 Consumption of these foods is not recommended in the first two years of life, as they have negative health impacts in the short or long term.2 However, their introduction occurs early, even in the first semester of life, a period for which exclusive breastfeeding is recommended.2-4

Ultra-processed foods are industrially produced, in various stages of processing, and have a high amount of ingredients such as salt, sugars, fats, preservatives and additives, among others.2,5 In addition, they are highly palatable, produced to offer pleasant and attractive flavors, which can generate addiction and influence eating habits throughout life.2,6 Consumption of ultra-processed foods is related to increased overweight/obesity, dyslipidemias, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and allergies in children, adolescents and adults.6-11

Adequate and healthy eating, on the other hand, is an important health promotion factor, which is fundamental for satisfactory growth and child development, especially in the first two years of life. Therefore, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended in the first 6 months, and then complemented with other foods - fresh or minimally processed - up to 2 years or over.2 The positive impacts of breastfeeding include reduction of the infant mortality rate, protection against infections, decreased risk of chronic diseases, improvement of oral cavity performance and intelligence levels.2,12-14

A study conducted in southeastern Brazil observed that early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding was associated with higher consumption of ultra-processed foods in preschoolers.15 Breastfeeding for less than 6 months was associated with higher scores of inadequate complementary feeding in children receiving care at a Primary Health Care Center in a municipality in the interior region of São Paulo state.16 Furthermore, the literature points to high consumption of ultra-processed foods by infants in Brazil, especially biscuits, jelly and 'petit suisse' cheese.3,4

No studies were found to assess the influence of exclusive breastfeeding on the introduction of ultra-processed foods in the first year of life, despite the importance of adequate child nutrition in this first period and its repercussions, both in childhood and in adulthood.2

The objective of this study was to analyze association between exclusive breastfeeding and the introduction of ultra-processed foods in children under 12 months old.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study, linked to a larger project entitled 'Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practice follow-up in children under 1 year of age living in the municipality of Vitória da Conquista - Bahia',17 conducted with mothers/children from the urban area of the municipality, from February 2017 to October 2018. The cohort study data collection, performed in all maternity hospitals in the municipality (February to October 2017), continued in subsequent visits to the participants' houses, when the children were 30 days old (March to December 2017), 6 months old (July 2017 to May 2018) and 12 months old (February to October 2018). This study used data collected in maternity hospitals when the children were 6 and 12 months old.

Vitória da Conquista, a municipality in southwestern Bahia, the third largest in the state in terms of territorial extension and fifth largest in the interior region of the Northeast, covers an area of 3,705.838km2 and had a human development index (HDI) of 0.678 in 2010; its estimated population for 2020 is 341,128 inhabitants.18 There are four maternity hospitals in the municipality: one of them provides care exclusively via the Brazilian National Health System (SUS); another provides only private care; while a further two provide both public and private care. In 2016, the four maternity hospitals in the municipality performed 5,541 deliveries.

The study included healthy mothers and their healthy live newborns from the urban area of Vitória da Conquista who did not need hospitalization in an intensive care unit (ICU), non-twin and with gestational age equal to or greater than 37 weeks. Mothers with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and children born with malformations that compromised breastfeeding, such as cleft palate, were considered ineligible.

The sample was selected in the maternity hospitals in the municipality, during visits made by undergraduate and graduate students responsible for data collection. On each day of the visits, three 'mother/live birth' pairs were selected at random 24 hours postpartum. If on the day of the visit, there were only three or fewer mother/live birth pairs at 24 hours postpartum, all of them were invited to participate as long as they met the inclusion criteria. Three pairs of mothers/live births were selected per visit at each maternity hospital, to enable follow-up of the participants over time.

After selecting the sample, information continued to be collected both from the medical records of the maternity hospitals and also through interviews in which a questionnaire was administered. Subsequently, three home visits were made after the children turned 30 days, six months and 12 months of life. Questionnaires were administered on all three occasions. The data obtained in the maternity hospital and selected for this study was comprised of: socioeconomic, demographic, maternal, paternal, gestational and breastfeeding information in the first hour of life. The interview at 6 months of age included information about the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and at 12 months, maternal information, such as work and marital status and about the child, including guidance on complementary feeding, person responsible for feeding the child, total breastfeeding, introduction of ultra-processed foods, age at which these foods were given for the first time, and whether the child attended or had attended day care or school.

The outcome variable of this study was the introduction of four or more types of ultra-processed foods, polarized between 'No' and 'Yes'. In order to define the items of this variable, the mothers were asked, at the time of the interview, about whether they gave their children 11 types of ultra-processed products - artificial juice, soft drink, yogurt/dairy drink, 'petit suisse' cheese, chocolate, biscuits, stuffed cookies, sweet food, snacks, instant noodles and sausage - before the child was 12 months old.5,19

The independent variable studied was exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), which was asked about in the interview when the children were 6 months old, based on the mother's answer to the following question:

"How long has your child been breastfed exclusively?"

The answer to this question was categorized into days: <120; 120-179; and ≥180. This categorization was based on the median EBF of 120 days and the recommendation for EBF up to 180 days.2 EBF was considered when the infant received only breast milk, directly from the breast or pumped beforehand, without provision of any other liquid or solid - except for medications, vitamins and mineral supplements.2

The covariates of interest corresponded to socioeconomic characteristics of the mother, father and child:

family income (in minimum wages: <1; ≥1);

maternal and paternal education (in years of studies: <8; ≥8);

maternal and paternal age (in years: <20; 20- 34; ≥35);

maternal race/skin color (white/yellow; black/brown);

maternal work (no; yes);

maternal marital status (without partner; with partner);

parity (primiparous; multiparous);

number of prenatal consultations (<6; ≥6);

guidance of a health professional on complementary feeding (no; yes);

attends or has attended day care or school (no; yes);

person responsible for feeding the child (mother or father; other); and

breastfeeding in the first hour of life (no; yes)

To calculate the sample size of the cohort, 59.3% prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 30 days of life was used as reference. This is a cohort study conducted with mothers/babies in the first month of lactation, in Feira de Santana, Bahia,20 taking relative risk of 1.2, power of 80% and a 95% confidence level. The minimum number for the study sample was 252, to which 30% compensation was added for possible losses, resulting in a sample of 328 mothers/children. The number of mothers/live births selected in each maternity hospital was proportional to the number of deliveries performed in each of them. The power of the sample was calculated to be 98.6%, considering a 95% confidence interval and the incidence of introduction of ultra-processed foods according to exclusive breastfeeding obtained in this study.

To characterize the sample, categorical variables were presented as absolute (n) and relative (%), and continuous variables, such as means and standard or median deviations. Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used in order to assess the differences between the proportions of mothers/children who remained in the study and those lost to follow-up. The differences between the proportions of introduction of the ultra-processed foods studied, according to the categories of duration of exclusive breastfeeding, were assessed by the linear trend test. Poisson regression with robust variance was used to analyze the influence of exclusive breastfeeding on the introduction of ultra-processed foods, estimating the crude and adjusted relative risks and respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

For the statistical adjustment, the stepwise-forward method was used, according to which the variables are inserted, one by one, in the multiple regression model, hierarchically and in decreasing order of statistical significance with the outcome, adopting p<0.20 as the entry criterion. The variables used as adjustment factors were included using three hierarchical models:

in model 1, family income, maternal education, paternal education and maternal work;

in model 2, maternal age, paternal age, maternal marital status, parity and number of prenatal consultations were added; and

in model 3, guidance of health professionals on complementary feeding was incorporated and the child attending or having attended day care or school.

Association was considered to be statistically significant when p≤0.05. The Akaike criterion (AIC) was used to assess the quality of the adjustment. The data were analyzed using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, USA).

The study project was submitted to the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Multidisciplinary Institute of Health, Federal University of Bahia (CEP-Seres Humanos/IMS/UFBA), and was approved: Protocol No. 1,861,163 and Certificate of Submission for Ethical Appraisal (CAAE) No. 62807516.2.0000.5556, both issued on December 12, 2016. The participating mothers signed the Free and Informed Consent Form.

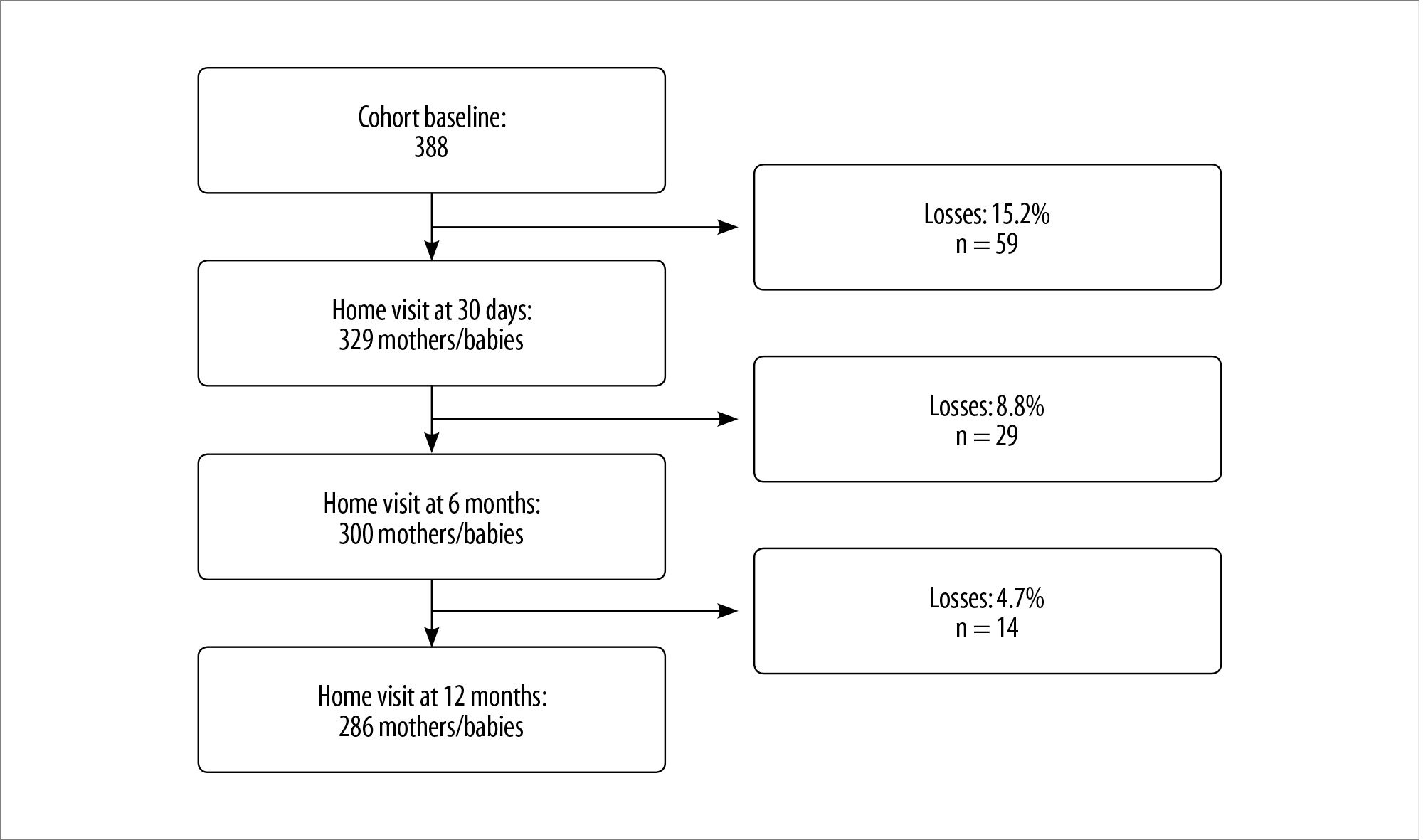

Figure 1 - Process of the sample of mothers/babies according to the cohort study follow-up, Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, 2018

Table 1 Socioeconomic, maternal and gestational, paternal and related characteristics of children under 12 months (N=286), Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, 2018

| Characteristics | n | % | 95%CIa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | |||

| Family incomeb (in minimum wages) | |||

| ≤1 | 70 | 26.0 | 21.1;31.6 |

| >1 | 199 | 74.0 | 68.4;78.9 |

| Maternal education (in years of study) | |||

| ≤8 | 65 | 22.7 | 18.2;28.0 |

| >8 | 221 | 77.3 | 72.0;81.8 |

| Paternal schoolingb (in years of study) | |||

| ≤8 | 76 | 28.3 | 23.2;34.0 |

| >8 | 193 | 71.7 | 66.0;76.8 |

| Maternal and gestational, and paternal | |||

| Maternal age (in years) | |||

| <20 | 34 | 11.9 | 8.6;16.2 |

| 20-34 | 201 | 70.3 | 64.7;75.3 |

| ≥35 | 51 | 17.8 | 13.8;22.7 |

| Paternal ageb (in years) | |||

| <20 | 5 | 1.8 | 0.7;4.2 |

| 20-34 | 184 | 64.8 | 59.0;70.2 |

| ≥35 | 95 | 33.4 | 28.2;39.2 |

| Maternal skin race/color | |||

| White/yellow | 69 | 24.1 | 19.5;29.5 |

| Black/brown | 217 | 75.9 | 70.5;80.5 |

| Maternal work | |||

| No | 126 | 44.1 | 38.4;49.9 |

| Yes | 160 | 55.9 | 50.1;61.6 |

| Maternal marital status | |||

| With partner | 37 | 13.0 | 9.5;17.4 |

| Without partner | 248 | 87.0 | 82.6;90.5 |

| Parity | |||

| Primiparous | 141 | 49.3 | 43.5;55.1 |

| Multiparous | 145 | 50.7 | 44.9;56.5 |

| Number of prenatal consultations | |||

| <6 | 50 | 17.5 | 13.5;22.4 |

| ≥6 | 236 | 82.5 | 77.6;86.5 |

| Child-related | |||

| Guidance of a healthcare professional on complementary feeding | |||

| No | 94 | 32.9 | 27.6;38.6 |

| Yes | 192 | 67.1 | 61.4;72.4 |

| Attends or has attended day care or school | |||

| No | 273 | 95.5 | 92.3;97.3 |

| Yes | 13 | 4.5 | 2.6;7.7 |

| Person responsible for feeding the child | |||

| Mother or father | 216 | 75.5 | 70.2;80.2 |

| Other | 70 | 24.5 | 19.8;29.8 |

| Amount of ultra-processed foods | |||

| <4 | 171 | 59.8 | 54.0;65.3 |

| ≥4 | 115 | 40.2 | 34.6;46.0 |

| Breastfeeding in the first hour of life | |||

| No | 148 | 51.7 | 45.9;57.5 |

| Yes | 138 | 48.3 | 42.5;54.1 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (in days) | |||

| <120 | 140 | 48.9 | 43.2;54.8 |

| 120-179 | 99 | 34.6 | 29.3;40.3 |

| ≥180 | 47 | 16.4 | 12.5;21.2 |

a) 95%CI : 95% confidence interval; b) Family income (n=17), paternal education (n=17) and paternal age (n=12) presented n lower than 286 - data unknown.

Table 2 - Incidence of introduction of ultra-processed foods in children under 12 months of age, according to categorization of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding (N=286), Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, 2018

| Ultraprocessed foods | Percentage introduction of ultra-processed foods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breastfeeding <120 days n (%) | Exclusive breastfeeding 120-179 days n (%) | Exclusive breastfeeding ≥180 days n (%) | p-valuea | |

| Cookie/Biscuit | 128 (91.4) | 89 (89.9) | 42 (89.4) | 0.627 |

| Petit suisse cheese | 106 (75.7) | 66 (66.7) | 22 (46.8) | <0.001 |

| Sweet food | 67 (47.9) | 38 (38.4) | 18 (38.3) | 0.147 |

| Stuffed cookie | 46 (32.9) | 24 (24.2) | 7 (14.9) | 0.012 |

| Snack | 36 (25.7) | 14 (14.1) | 4 (8.5) | 0.003 |

| Instant noodles | 36 (25.7) | 12 (12.1) | 4 (8.5) | 0.002 |

| Chocolate | 32 (22.9) | 11 (11.1) | 4 (8.5) | 0.006 |

| Yogurt/dairy drink | 32 (22.9) | 22 (22.2) | 9 (19.1) | 0.629 |

| Soft drink | 25 (17.9) | 11 (11.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0.004 |

| Artificial fruit juice | 25 (17.9) | 9 (9.1) | 2 (4.3) | 0.007 |

| Sausages | 22 (15.7) | 10 (10.1) | 2 (4.3) | 0.028 |

a) Linear trend test.

Table 3 - Crude and adjusted analysis of the association between exclusive breastfeeding and introduction of four or more ultra-processed foods in the first year of life, Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, 2018

| Exclusive breastfeeding (in days) | Introduction of four or more ultra-processed foods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude analysis | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| RRa (95%CIb) | p-valuec | RRa (95%CIb) | p-valuec | RRa (95%CIb) | p-valuec | RRa (95%CIb) | p-valuec | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| <120 | 2.76 (1.50;5.07) | 3.05 (1.51; 6.14) | 2.86 (1.44;5.67) | 2.94 (1.51;5.71) | ||||

| 120-179 | 1.69 (0.88;3.25) | 2.01 (0.97;4.17) | 2.07 (1.02;4.22) | 2.17 (1.09;4.30) | ||||

| ≥180 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Akaike criterion | 432.39 | 356.93 | 351.70 | 349.58 | ||||

a) RR: relative risk; b)95% CI: 95% confidence interval; c) Poisson regression with robust variance estimator.

Notes:

Model 1: adjusted for the 'family income', 'maternal education', 'paternal schooling' and 'maternal work' variables.

Model 2: model 1 + 'maternal age', 'paternal age', 'maternal marital status', 'parity' and 'number of prenatal visits'.

Model 3: model 2 + 'guidance of health professional on complementary feeding' and 'attends or has attended day care or school'.

Results

The baseline of the cohort in the maternity hospitals was comprised of 388 mothers/children. After losses, the final sample of this study was 286 mothers/children followed up to 12 months of life (Figure 1). The losses occurred due to a change of telephone number, address or city, and due to withdrawal. There were no statistically significant differences between the study sample and the losses to follow-up (from maternity hospital to 12 months), according to the 'family income' (p=0.297), 'paternal schooling' (p=0.060), 'maternal age' (p=0.842) and 'parity' (p=0.285) variables (data not shown in tables).

Of the total number of interviewees, most mothers lived with family income above 1 minimum wage (74.0%), had more than 8 years of schooling (77.3%), were between 20 and 34 years of age (70.3%) (median: 28 years) and 50.7% of them were multiparous. Most fathers had more than 8 years of schooling (71.7%) and were between 20 and 34 years old (64.8%) (median: 31 years). Regarding the children's diet, 67.1% of the mothers reported that they had received guidance from health professionals on complementary feeding. As for their children, 40.2% had received four or more types of ultra-processed foods; and almost half of them had received breast milk exclusively for less than 120 days (48.9%) (Table 1). Median introduction of ultra-processed foods was 180 days (minimum of 90 days; maximum of 330 days).

Significantly higher incidence rates of introduction of 'petit suisse' cheese (75.7%), stuffed crackers (32.9%), snacks (25.7%), instant noodles (25.7%), chocolate (22.9%), artificial fruit juice (17.9%), soft drink (17.9%) and sausages (15.7%) in the first year of life were found among children who had received exclusive breastfeeding for less than 120 days. It could be seen that the shorter the duration of exclusive breastfeeding, the higher the proportions of introduction of ultra-processed foods (Table 2).

In the crude analysis, exclusive breastfeeding for <120 days increased the risk of introduction of four or more ultra-processed foods. In the adjusted analysis, exclusive breastfeeding for less than 120 days of life (RR=2.94 - CI 95% 1.51;5.71) and from 120 to 179 days of life (RR=2.17 - CI95% 1.09;4.30) increased the risk of introducing four or more ultra-processed foods in the first year of life, when compared to exclusive breastfeeding for 180 days or more. It could be seen that the power of association between the main explanatory variable and the outcome increased as the models were adjusted (Table 3). Duration of exclusive breastfeeding influenced the introduction of four or more ultra-processed foods in the first year of life, regardless of the adjustment covariates.

Discussion

The findings of this study show that the frequency of introduction of four or more ultra-processed foods in the 5 year of life and exclusive breastfeeding for less than 120 days was high. Children who received exclusive breastfeeding for less than 180 days, presented a higher risk of having ultra-processed foods (four or more) introduced in the first years of life. The findings are contrary to the guidelines of the Ministry of Health, which recommend EBF up to six months and that ultra-processed foods should not be introduced before 2 years of life.2

Considering that foods introduced in the first years of life influence the child's eating habits, this study was important because it addressed EBF as a determining factor for subsequent food introduction. Among the limitations of the research is the fact that it does not take into account the frequency and quantity of the ultra-processed foods consumed, but only if they had ever been given and at what age. A specific instrument was not applied to evaluate the foods separately, according to the degree of processing, which may affect the number of ultra-processed foods consumed. The four product cutoff point was defined based on the median distribution in the sample, considering that only 12 children had not received any ultra-processed product in the first year of life. This analysis included foods that are consumed more frequently by the population studied. Finally, despite being ultra-processed food, infant formula was not included in this study because it is a recommended food for children who are not breastfed.

A high frequency of introduction of ultra-processed foods in the first year of life was also found in other studies carried out in southern Brazil.3.4 One of these studies, when evaluating the introduction of foods not recommended for children under 1 year of age, living in low-income municipalities in the southern region of the country, found that 78.9% of these children had received sweet/salted biscuits, 73.8% 'petit suisse' cheese and 41.9% sweets/lollipops before 12 months of life.3 Another study, conducted with children aged 4 to 24 months hospitalized in a tertiary hospital, also in southern Brazil, found that 21% of the hospitalized children had not received any type of ultra-processed foods, while the median amount of introduction of these foods was five types,4 among the remainder.

Ultra-processed foods should not be given to children in the first 2 years of life, because they are poor in nutrients, contain high energy content, irritate the gastric mucosa and impair digestion and absorption of nutrients.2,21 However, these foods are produced with pleasant and attractive flavors, so they entail addiction and influence the child's dietary preferences and, consequently, their consumption habits throughout life.2,6 It is important for original flavors to be introduced to the child, by giving fresh or minimally processed foods.2 In addition, ultra-processed foods are risk factors for morbidity and mortality, both in childhood and in adulthood: increased total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol,9 increased waist circumference,8 overweight/obesity,7 hypertension10 and asthma11, for example.

Regarding breastfeeding, global data revealed that 2 out of 5 children under 6 months were exclusively breastfed in 2018.22 Boccolini et al.,23 when evaluating the breastfeeding trend in Brazil, found 36.6% prevalence of EBF in children under 6 months of age in 2013. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Brazilian studies published between 2000 and 2015, found 25% prevalence of EBF in the first 6 months of the child's life.24 The findings of that review were higher than those of this study, according to which 16.4% of the children were exclusively breastfed for 180 days or more. It is possible that these differences result from the categorization of EBF time: this study considered interruption in three periods, before 120 days, from 120 to 179 days and at 180 days or more, while the other studies evaluated the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in children under 6 months.

Higher incidence rates of ultra-processed feeding in children under 12 months of age (e.g., artificial fruit juice, soft drink, ‘petit suisse’ cheese, chocolate, stuffed crackers, snacks and instant noodles) were found in children who received EBF for less than 120 days of life. The risk of introducing four or more ultra-processed foods among children under exclusive breastfeeding for less than 120 days of life was 194% higher when compared to the same risk for those who were breastfed exclusively for 180 days or more. Among those who were breastfed exclusively from 120 to 179 days, this risk was 117% higher.

Provision of ultra-processed foods associated with exclusive breastfeeding for less time, as found in this study, corroborates the findings of other studies conducted with preschoolers.15,25 A birth cohort study conducted in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, analyzed dietary patterns of children aged 6 years and found high consumption of snacks and treats associated with exclusive breastfeeding for less than one month.25 A study that evaluated association between duration of EBF and consumption of ultra-processed foods, fruits and vegetables in children aged 4 to 7 years, born in Viçosa, Minas Gerais, observed that, for each 1% increase in the duration of EBF, there was a 0.7% decrease in the consumption of ultra-processed foods; while EBF for less than four months increased by 70% the chance of being in the highest tertile of energy consumption of these foods.15

Breastfeeding increases the child's acceptance to a wider variety of foods, especially vegetables.26 The flavors of foods consumed by mothers during the breastfeeding period are transmitted to the children by breast milk, which influences the introduction of complementary feeding - which should occur from six months on.2 Furthermore, mothers who breastfeed for longer may have a healthier lifestyle and be more aware of the importance of this habit, giving more fruit and vegetables to their children.27 The food intake of mothers and caregivers also influences the children’s diet, and it is common for them to give children food of their preference, regardless of whether or not these foods are recommended for children under 2 years of age.12 In turn, parents who consume more fruit and vegetables provide more of these foods to their children.28

Given infant dependence with regard to food consumption, the need for mothers and caregivers to receive adequate guidance on healthy eating,2 including breastfeeding and complementary feeding, stands out. Such guidance should take into account not only nutritional needs but also the social and structural context in which the child lives.29

As such, interruption of EBF and provision of early ultra-processed foods may be related to both the lack of information mothers and caregivers have about healthy eating and to the communication strategies used by health professionals, as obstacles to adhering to the guidance provided.4,30

In view of the results of this study, it is concluded that the frequency of introduction of ultra-processed foods in the first year of life and early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding - EBF - were high. And that shorter duration of exclusive breastfeeding influences the provision of ultra-processed foods in children under 12 months old. Thus, this study can contribute to the planning, implementation and execution of actions, especially in Primary Health Care services, such as the Family Health Strategy (FHS) and the Family Health Support Center (FHSC). These actions should be based on the National Food and Nutrition Policy, other maternal and child health care policies and updated guidelines, such as the 'Food Guide for children under 2 years old’2 published by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

REFERENCES

1. Martins APB, Levy RB, Claro RM, Moubarac JC, Monteiro CA. Participação crescente de produtos ultraprocessados na dieta brasileira (1987-2009). Rev Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2013 set [citado 2020 jun 04];47(4):656-65. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2013047004968 [ Links ]

2. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Departamento de Promoção da Saúde. Guia alimentar para crianças brasileiras menores de dois anos [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2019 [citado 2020 dez 15]. 265 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/guia_da_crianca_2019.pdf [ Links ]

3. Dallazen C, Silva SA, Gonçalves VSS, Nilson EAF, Cispim SP, Lang RMF, et al. Introdução de alimentos não recomendados no primeiro ano de vida e fatores associados em crianças de baixo nível socioeconômico. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2018 [citado 2020 jun 04];34(2):e00202816. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00202816 [ Links ]

4. Giesta JM, Zoche E, Corrêa RS, Bosa VL. Fatores associados à introdução precoce de alimentos ultraprocessados na alimentação de crianças menores de dois anos. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2019 jul [citado 2020 jun 04];24(7):2387-97. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018247.24162017 [ Links ]

5. Monteiro C, Cannon G, Lawrence M, Costa Louzada ML, Machado PP. Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system [Internet]. Rome: FAO; 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 15]. 44 p. Availabre from: Availabre from: http://www.fao.org/fsnforum/resources/fsn-resources/ultra-processed-foods-diet-quality-and-health-using-nova-classification [ Links ]

6. Organización Panamericana de la Salud - OPAS. Alimentos y bebidas ultraprocesados en América Latina: tendencias, efecto sobre la obesidad e implicaciones para las políticas públicas [Internet]. Washington: OPS; 2015 [citado 2020 jun 04]. Disponible: Disponible: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/7698/9789275318645_esp.pdf?seque [ Links ]

7. Louzada ML, Baraldi LG, Steele EM, Martins APB, Canella DS, Moubarac JC, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Brazilian adolescents and adults. Prev Med [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2020 Dec 15];81:9-15. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.018 [ Links ]

8. Costa CS, Rauber F, Leffa PS, Sangalli CN, Campagnolo PDB, Vitolo MR. Ultra-processed food consumption and its effects on anthropometric and glucose profile: A longitudinal study during childhood. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis [Internet]. 2019 Feb [cited 2020 Dec 15];29(2):177-84. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2018.11.003 [ Links ]

9. Rauber F, Campagnolo PDB, Hoffman DJ, Vitolo MR. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children's lipid profiles: a longitudinal study. Nutr Metab and Cardiovasc Dis [Internet]. 2015 Jan [cited 2020 Dec 15];25(1):116-22. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.08.001 [ Links ]

10. Mendonça RD, Lopes AC, Pimenta AM, Gea A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a mediterranean cohort: the seguimiento universidad de navarra project. Am J Hypertens [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2020 Dec 15];30(4):358-66. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpw137 [ Links ]

11. Melo B, Rezende L, Machado P, Gouveia N, Levy R. Associations of ultra-processed food and drink products with asthma and wheezing among Brazilian adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol [Internet]. 2018 Apr [cited 2020 Dec 15];29(5):504-11. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.12911 [ Links ]

12. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Saúde da criança: aleitamento materno e alimentação complementar [Internet]. 2. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2015 [citado 2020 jun 04]. 184 p. (Cadernos de Atenção Básica; n. 23). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/saude_crianca_aleitamento_materno_cab23.pdf [ Links ]

13. Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MIC, Boccolini PMM. O papel do aleitamento materno na redução das hospitalizações por pneumonia em crianças brasileiras menores de 1 ano. J. Pediatr [Internet]. 2011 out [citado 2020 jun 04];87 (5):399-404. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0021-75572011000500006 [ Links ]

14. Boccolini CS, Boccolini P. Relação entre aleitamento materno e internações por doenças diarreicas nas crianças com menos de um ano de vida nas Capitais Brasileiras e Distrito Federal, 2008. Epidemiol Serv Saúde [Internet]. 2011 jan-mar [citado 2020 jun 04];20(1):19-26. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742011000100003 [ Links ]

15. Fonseca PCA, Ribeiro SAV, Andreoli CS, Carvalho CA, Pessoa MC, Novaes JF, et al. Association of exclusive breastfeeding duration with consumption of ultra-processed foods, fruit and vegetables in Brazilian children. Eur J Nutr [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2020 Dec 15];58(7):2887-94. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1840-9 [ Links ]

16. Mais LA, Domene SMÁ, Barbosa MB, Taddei JAAC. Diagnóstico das práticas de alimentação complementar para o matriciamento das ações na Atenção Básica. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2014 [cidado 2020 jun 04];19(1):93-104. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232014191.2168 [ Links ]

17. Sousa PKS, Novaes TG, Magalhães EIS, Gomes AT, Bezerra VM, Pereira NM, et al . Prevalência e fatores associados ao aleitamento materno na primeira hora de vida em nascidos vivos a termo no sudoeste da Bahia, 2017. Epidemiol Serv Saúde [Internet]. 2020 [citado 2020 nov 05];29(2):e2018384. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742020000200016 . [ Links ]

18. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Cidades e Estados [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2020 [citado 2020 dez 15]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/ba/vitoria-da-conquista/panoramaba/vitoria-da-conquista.html [ Links ]

19. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Guia alimentar para a população brasileira [Internet]. 2. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2014 [citado 2020 jun 04]. 156 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/guia_alimentar_populacao_brasileira_2ed.pdf [ Links ]

20. Vieira GO, Martins CC, Vieira TO, Oliveira NF, Silva LR. Fatores preditivos da interrupção do aleitamento materno exclusivo no primeiro mês de lactação. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2010 Oct [cited 2020 Jun 04];86(5):441-4. Available from: Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0021-75572010000500015 [ Links ]

21. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Departamento de Promoção da Saúde. Dez passos para uma alimentação saudável: guia alimentar para crianças menores de dois anos: um guia para o profissional da saúde na atenção básica [Internet]. 2. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2013[citado 2020 jun 11]. 72 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.redeblh.fiocruz.br/media/10palimsa_guia13.pdf [ Links ]

22. United Nations International Children`s Emergency Fund - UNICEF. Infant and young child feeding [Internet]. New York: UNICEF; 2019 [cited 2020 Jun 11]. Available from: Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding/ [ Links ]

23. Boccolini CS, Boccolini PMM, Monteiro FR, Venâncio SI, Giugliani ERJ. Tendência de indicadores do aleitamento materno no Brasil em três décadas. Rev. Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2017 [citado 2020 jun 11];51:108. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2017051000029 [ Links ]

24. Pereira-Santos M, Santana MS, Oliveira DS, Nepomuceno Filho RA, Lisboa CS, Almeida LMR, et al . Prevalência e fatores associados à interrupção precoce do aleitamento materno exclusivo: metanálise de estudos epidemiológicos brasileiros. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant [Internet]. 2017 mar [citado 2020 ago 02];17(1):59-67. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-93042017000100004 [ Links ]

25. Santos LP, Assunção MCF, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Barros AJD. Dietary intake patterns of children aged 6 years and their association with socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, early feeding practices and body mass index. BMC public health [Internet]. 2016 Oct [cited 2020 Jun 11];16(1):1055. Available from: Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2Fs12889-016-3725-2 [ Links ]

26. Maier AS, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Leathwood PD, Issanchou SN. Breastfeeding and experience with variety early in weaning increase infants' acceptance of new foods for up to two months. Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2008 Dec [cited 2020 Dec 15];27(6):849-57. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2008.08.002 [ Links ]

27. Möller LM, Hoog MLA, van Eijsden M, Gemke RJBJ, Vrijkotte TGM. Infant nutrition in relation to eating behaviour and fruit and vegetable intake at age 5 years. Br J Nutr [Internet]. 2013 Feb [cited 2020 Dec 15];109(3):564-71. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114512001237 [ Links ]

28. Cooke LJ, Wardle J, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M. Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2004 Apr [cited 2020 Dec 15];7(2):295-302. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2003527 [ Links ]

29. Nielsen A, Michaelsen KF, Holm L. Parental concerns about complementary feeding: differences according to interviews with mothers with children of 7 and 13 months of age. Eur J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2013 Nov [cited 2020 Jun 26];67(11):1157-62. Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.165 [ Links ]

30. Broilo MC, Louzada ML, Drachler ML, Stenzel LM, Vitolo MR. Maternal perception and attitudes regarding healthcare professionals' guidelines on feeding practices in the child's first year of life. J Pediatr [Internet]. 2013 Sep-Oct [cited 2020 Jun 26];89(5):485-91.Available from: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2013.01.005 [ Links ]

*Manuscript originated from the Master’s Degree dissertation in Public Health, by Jessica Prates Porto, entitled 'Introduction of ultra-processed foods and associated factors in children living in the municipality of Vitória da Conquista - Bahia' and submitted to the Multidisciplinary Institute of Health of the Universidade Federal da Bahia (IMS/UFBA) in August 2020. The study received financial support in the form of a Master's scholarship, granted to the student Jessica Prates Porto by the Bahia State Foundation for Research Support (Fapesb): Scholarship Grant Term No. BOL07587/2018.

Received: August 07, 2020; Accepted: November 10, 2020

texto en

texto en