Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde

versión impresa ISSN 1679-4974versión On-line ISSN 2237-9622

Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde vol.31 no.1 Brasília 2022 Epub 22-Abr-2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1679-49742022000100025

Original Article

Association between parental supervision and bullying victimization and perpetration in Brazilian adolescents, Brazilian National Survey of Student’s Health 2015

1 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Nutrição, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

2 Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Faculdade de Medicina, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil

3 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Medicina Social, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Objective:

To analyze the association between parental supervision characteristics and different bullying roles among Brazilian adolescent school students.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study using data from the National School Student Health Survey (PeNSE) 2015. Frequent meals with parents/guardians, knowing about students’ free time activities and checking their homework were the parental practices assessed. Logistic regression was used for association between these practices and bullying (perpetration and victimization), presented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

Results:

Among 102,072 school students, frequent meals with parents or guardians [ORvictim = 0.86 (95%CI 0.84;0.89); ORperp = 0.85 (95%CI 0.82;0.88)], checking homework [ORvictim = 0.95 (95%CI 0.92;0.97); ORperp = 0.76 (95%CI - 0.74;0.78)], and parents’ or guardians’ knowledge about students’ free time activities [ORperp = 0.70 (95%CI 0.68;0.73] were inversely associated with bullying.

Conclusion:

Greater parental supervision reduced the odds of bullying victimization and perpetration among adolescent school students.

Keywords: Parent-Child Relations; Parenting; Bullying; Adolescent; Observational Study

Study contributions

Main results

Adopting parental supervision practices (frequently having meals with parents or legal guardians, checking homework and parents or legal guardians knowing about school students’ free time activities) reduced the odds of bullying.

Introduction

Bullying, a type of violence that occurs between peers, has three main characteristics: intentionality, repetition and power imbalance between aggressor and victim. It is a common event for adolescent school students.1 Bullying is considered to be an important public health problem, due to its magnitude and the serious consequences it has for the health and well-being of children and adolescents.2 The prevalence of this problem in various parts of the world, including Brazil, is high: in 2014, bullying victimization prevalence was 36%, while bullying perpetration prevalence was 35%.3 In Brazil, the three editions of the Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar [National School Student Health Survey (PeNSE)] showed an increasing trend in bullying among adolescent school students, from 14.2% in 2009, to 16.5% in 2012 and 21.7% in 2015.4

Most of the existing literature on bullying focuses on describing the profile of its victims and perpetrators, as well as individual and contextual risk factors related to experiencing these roles.5 The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) document entitled ‘Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying’ published in 2019, and the systematic review on predictors of bullying perpetration conducted by Álvarez-Garcia et al. and published in 2015, show that older boys living in violent settings with fewer friends are more likely to be victims and/or perpetrators of bullying.2,6 National and international studies observing the influence of the family context on bullying, especially the relationship parents establish with their children, are recent and for the most part address victimization.7-9

Parenting practices refer to the behavior and attitudes of parents towards caring for, educating and controlling their children.10 The habits and bonds established between parents and children are fundamental for their growth, development and for building their autonomy.11 According to the review conducted by Oliveira et al. in 2018, parental supervision, rule-setting, monitoring and positive communication are protective factors against bullying. In contrast, use of violence to solve conflicts between parents and children is a risk factor for bullying.12 Thus, the importance of family and peers in the adolescent socialization process becomes evident. Within this context, the school is an essential locus for reflection and discussion of vulnerabilities, development and preparation of adolescents.13 In Brazil the Programa Saúde na Escola [Health at School Program (PSE)]14 has health promotion and implementation of prevention activities as one of its guiding components. From this perspective, promotion of a culture of peace and rejection of any manifestation of violence stand out as health promotion strategies.

Considering the importance of parental supervision in the way adolescents relate to their peers, as well as the scarcity of national and international studies focusing on its influence on the perpetration of bullying,7-9 this study aims to contribute to expanding knowledge about the influence of parents in the different roles involved in bullying, as well as to contribute to the design and implementation of actions involving family, peers and school to promote health and prevent bullying.

The objective of this study was to analyze the association between parental supervision characteristics and different bullying roles among Brazilian adolescent school students.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study, based on data from the third edition of the PeNSE survey conducted in 2015. PeNSE is a population-based survey, conducted every three years by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), in partnership with the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education.15

The sample was selected using the cluster sampling procedure, in multiple stages, with the aim of estimating population parameters in diverse geographic domains. Data from the 2013 School Census were used to select the schools participating in the 2015 PeNSE survey, based on the inclusion criterion of schools that had 9th grade classes. In the case of schools that had one or two 9th grade classes, only one class was selected. When schools had three or more 9th grade classes, two classes were selected.15 All adolescents in the selected classes, present on the day data was collected, were considered eligible for the study.

The study population, therefore, included students attending the 9th grade (final year) of elementary school, enrolled at public and private schools, located in rural and urban areas of Brazil’s 26 state capitals and Federal District, interviewed through the 2015 PeNSE survey.

Data collection took place in 2015, using a self-administered, multi-item questionnaire, available via smartphone. The instrument had questions regarding the socioeconomic, demographic and family context, violence, safety and accidents, among others, and was based on international research with adolescent school students, such as the Global School-Based Student Health Survey, the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children study and the The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, as well as previous national population-based surveys.15

We accessed the PeNSE 2015 survey data via the IBGE website (https://bit.ly/ressn1_376B6LC) on June 11th 2020.

The parental supervision practices we analyzed were i) frequency of meals with parents or legal guardians, ii) parents or legal guardians knowing about school students’ free time activities and iii) parents or legal guardians checking homework. These exposures of interest were assessed by asking the following questions: Do you usually have lunch or dinner with your mother, father or guardian?; In the last 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians really know what you were doing in your free time?; and In the last 30 days how often did your parents or guardians check whether you had done your homework? For the purposes of the descriptive and analytical analysis, the meal frequency variable was categorized into up to 2 times a week, 3 to 4 times a week, and 5 or more times a week. The variables regarding knowing about free time activities and checking homework were categorized as: 0 (never); 1 (rarely); 2 (yes - sometimes/most of the time/always).

With regard to the outcomes - bullying victimization and perpetration -, these were measured by asking the following questions: In the last 30 days, how often did your schoolmates treat you well and/or were helpful to you?; In the last 30 days, how often did your schoolmates ridicule, tease, mock, intimidate or make fun of you so much that you became upset, annoyed, offended or humiliated?; and In the last 30 days, did you ridicule, tease, mock, intimidate or make fun of a schoolmate so much that they became upset, annoyed, offended or humiliated? In the data analysis, these variables were used in dichotomous form (yes; no).

The variables used to characterize the population and for adjusting the multivariate analyses were: sex (male; female); age (in years: under 15; 15 or over); race/skin color (White; Black; Yellow; Brown/Mixed; native Brazilian Indigenons); living with mother (yes; no); living with father (yes; no); living with both parents (yes; no); type of school (public; private).

The power of the study was calculated taking into consideration the design of the survey, the amount of exposed and unexposed participants, prevalence of parental supervision practices in these groups, and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The post hoc power of the study was 99.9%.

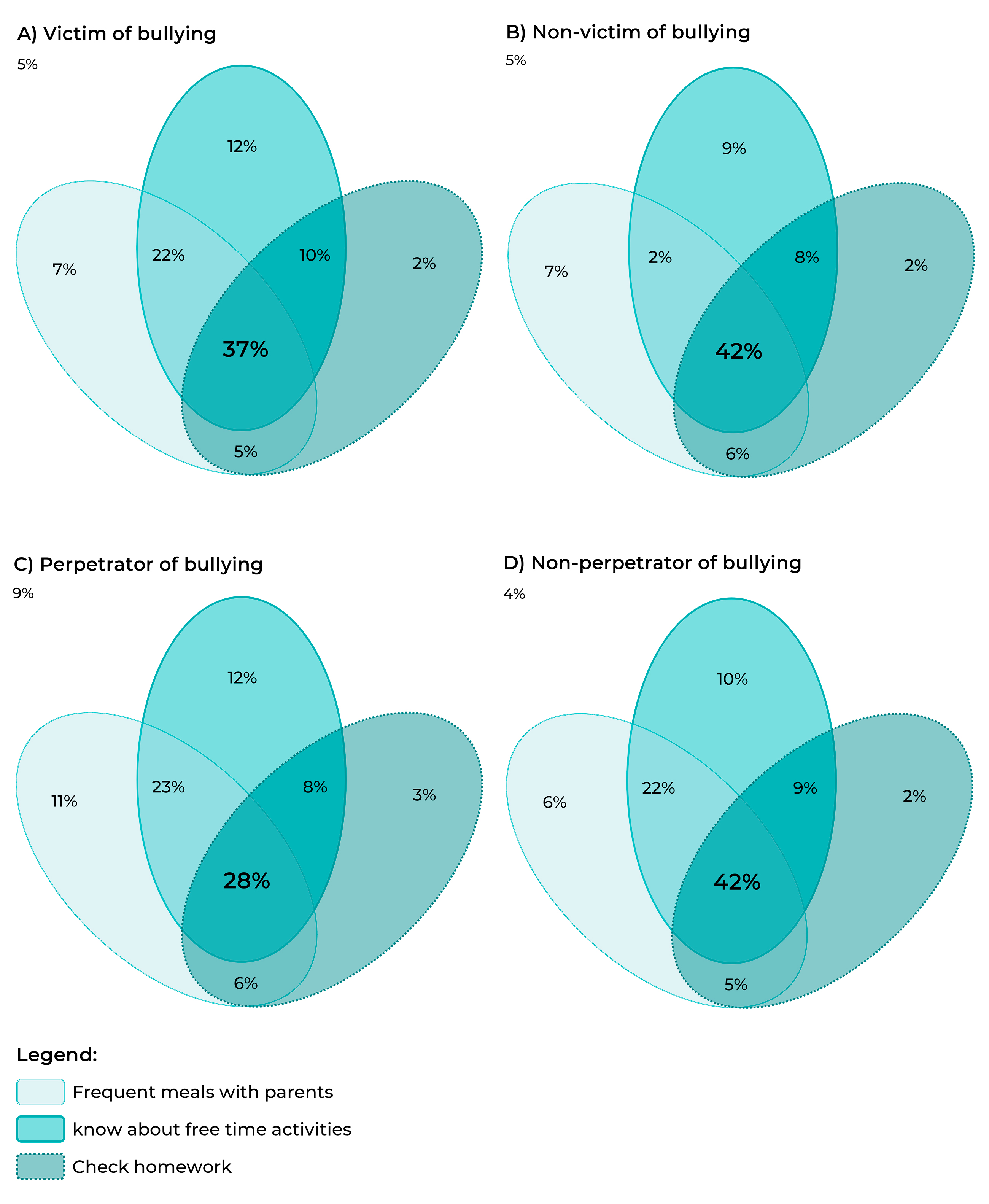

Initially, we performed descriptive analysis to identify the distribution of the variables and characterize the population studied. We calculated prevalence of bullying victimization and perpetration in some subgroups of the sample (age; sex; race/skin color; living with mother; living with father; type of school) and estimated the 95%CI. The parenting practices co-occurrence profile was represented graphically, using a Venn diagram, according to the adolescent’s role in bullying (victimization or perpetration). For the purposes of this analysis, the parental supervision variables were dichotomized: the variable regarding meal frequency was categorized into ≤4 times a week and ≥5 times a week, while the other supervision practices were categorized into 'no' and 'yes'.

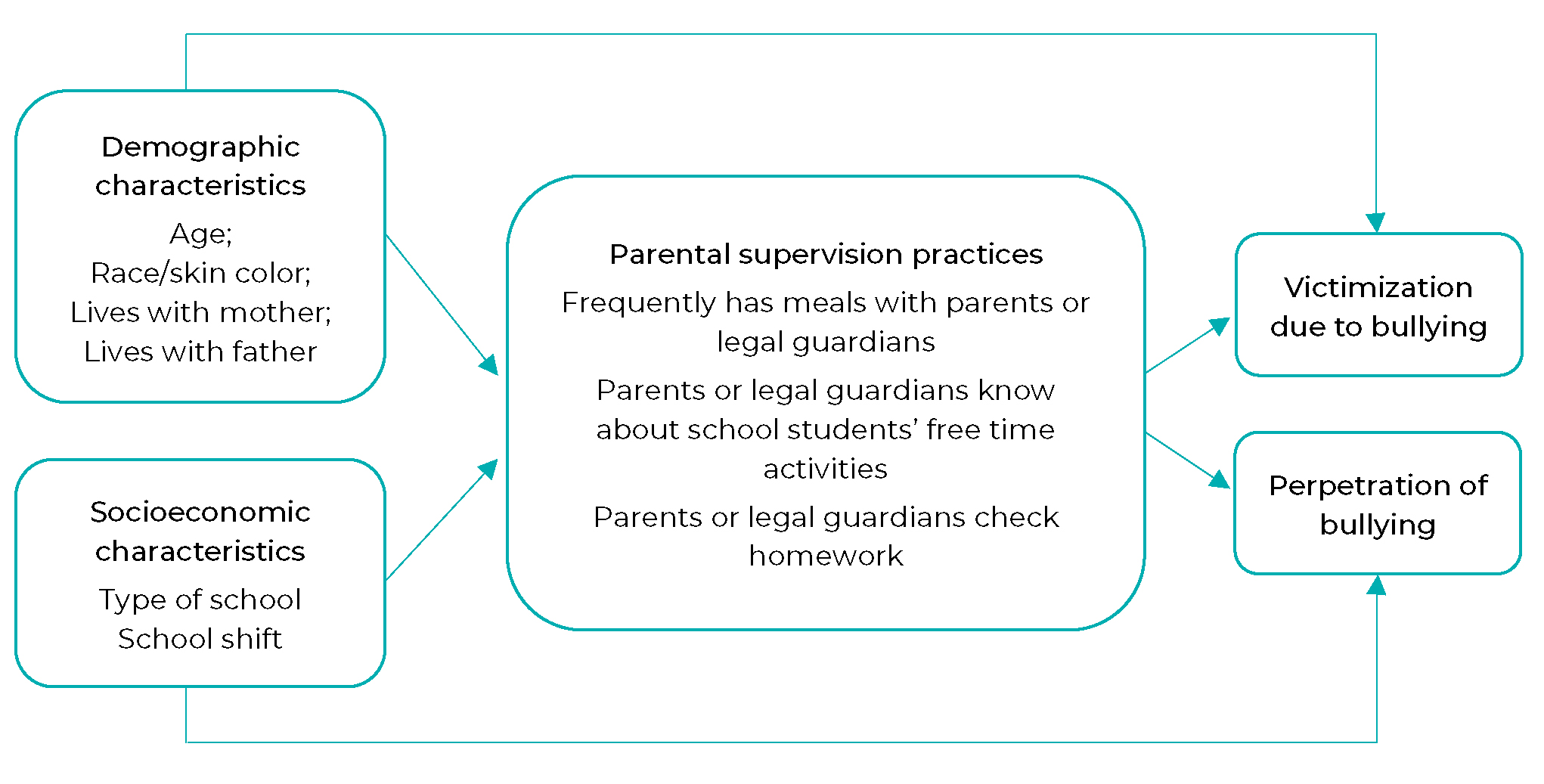

The crude and adjusted estimates of association of each parental practice (frequently having meals with parents or guardians, knowing about the free time activities and checking the homework of their children) with bullying victimization (odds ratio = ORvictim) and bullying perpetration (ORperp), and their respective 95%CI, were obtained using simple and multiple logistic regression analysis. In all models analyzed, the significance of the estimates was verified by the Wald test, considering a p-value <0.05 to be statistically significant. The multivariate analysis was guided by the theoretical-conceptual model, previously developed by the researchers (Figure 1), and adjusted by the demographic, socioeconomic, family and school context variables mentioned above. All analyses were performed using version 15.0 of the Stata statistical package, considering the sample structure and weighting to obtain population estimates, by means of the svy suite of commands.

Figure 1 Theoretical-conceptual model representative of variables related to parental supervision practices and bullying among adolescents

The PeNSE 2015 project was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee, which is linked to the National Health Council/Ministry of Health, as per Opinion No. 1.006.467, issued on March 30th 2015. Only students who signed the Informed Consent Form took part in the study. It should be noted that as the study used open-access public domain data with no identification of the participants, it was exempted from appraisal by the Research Ethics Committee.

Results

The study population was comprised of 102,072 students attending 9th grade at public and private schools in Brazil’s 26 state capitals and Federal District (3,160 schools and 4,159 classes). Table 1 shows the profile of the survey participants. Distribution of the sample according to sex was similar, most students were under 15 years old (69.3%), self-reported being of mixed race (43.1%), lived with both parents (59.3%), and attended public schools (85.5%). With regard to experiencing bullying, 46.6% (95%CI 45.9;47.3) reported being victims, while 19.8% (95%CI 19.2;20.3) said they were perpetrators of this type of violence. Regarding parental supervision practices, most students had their meals with their parents or guardians 5 times or more a week (73.9%), most stated that their parents or guardians were aware of their free time activities (80.5%), most and had their homework checked by them (55.9%).

Table 1 Characteristics of Brazilian students (n=102,072), National School Student Health Survey (PeNSE), 2015

| Variables | n | % (95%CIa) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||

| <15 | 68,871 | 69.3 (68.2;70.3) |

| ≥15 | 33,201 | 30.7 (29.7;31.8) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 42,290 | 48.7 (48.1;49.3) |

| Female | 52,782 | 51.3 (50.7;51.9) |

| Race/skin color | ||

| White | 33,775 | 36.1 (35.1;37.2) |

| Black | 12,849 | 13.4 (12.9;13.9) |

| Yellow | 4,580 | 4.1 (3.9;4.4) |

| Brown/mixed | 46,935 | 43.1 (42.2;43.9) |

| Native Brazilian Indigenous | 3,825 | 3.3 (3.1;3.5) |

| Lives with mother | ||

| No | 11,543 | 10.1 (9.7;10.4) |

| Yes | 90,458 | 89.9 (89.6;90.3) |

| Lives with father | ||

| No | 38,341 | 36.3 (35.6;37.0) |

| Yes | 63,600 | 63.7 (63.0;64.4) |

| Lives with both parents | ||

| No | 43,367 | 40.7 (40.0;41.5) |

| Yes | 58,669 | 59.3 (58.5;60.0) |

| Type of school | ||

| Public | 81,154 | 85.5 (83.4;87.5) |

| Private | 20,918 | 14.5 (12.5;16.6) |

| Frequency of meals with parents or legal guardians | ||

| ≤2 times a week | 23,980 | 22.6 (22.0;23.2) |

| 3-4 times a week | 3,963 | 3.5 (3.3;3.7) |

| ≥5 times a week | 74,129 | 73.9 (73.3;74.6) |

| Parents or legal guardians know about school students’ free time activities | ||

| Never | 11,057 | 10.8 (10.4;11.3) |

| Rarely | 8,884 | 8.7 (8.3;9.0) |

| Sometimes/most of the time/always | 82,131 | 80.5 (79.9;81.1) |

| Parents or legal guardians check homework | ||

| Never | 26,191 | 25.1 (24.5;25.7) |

| Rarely | 19,836 | 19.0 (18.5;19.5) |

| Sometimes/most of the time/always | 56,045 | 55.9 (55.1;56.5) |

| Victimization due to bullying | ||

| No | 56,584 | 53.4 (52.7;54.1) |

| Yes | 44,921 | 46.6 (45.9;47.3) |

| Perpetration of bullying | ||

| No | 82,595 | 80.2 (79.7;80.8) |

| Yes | 19,002 | 19.8 (19.2;20.3) |

a) 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

Table 2 shows the profile of the students interviewed according to their role in bullying. Victims of bullying were mostly female (50.6%), under 15 years old (72.2%), and students attending public schools (85.0%). Students who perpetrated bullying were mostly male (59.5%), under 15 years old (66.7%), self-reported being of brown skin color (42.0%), living with their mother (89.1%), living with their father (60.2%), and attending public schools (84.4%).

Table 2 Prevalence of bullying victimization and perpetration according to independent variables, among Brazilian students (n=102,072), National School Student Health Survey (PeNSE), 2015

| Variables | Victimization due to bullying | Perpetration of bullying | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95%CIa) | n | % (95%CIa) | |

| Age (in years) | ||||

| <15 | 31,366 | 72.2 (71.1;73.3) | 12,273 | 66.7 (65.0;68.3) |

| ≥15 | 13,555 | 27.8 (26.7;28.9) | 6,729 | 33.3 (31.7;35.0) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 22,035 | 49.4 (48.4;50.3) | 11,399 | 59.5 (58.2;60.9) |

| Female | 22,886 | 50.6 (49.7;51.6) | 7,603 | 40.5 (39.1;41.9) |

| Race/skin color | ||||

| White | 14,848 | 36.6 (35.3;37.9) | 5,960 | 35.7 (34.0;37.5) |

| Black | 5,593 | 13.2 (12.5;13.8) | 2,670 | 14.5 (13.5;15.6) |

| Asian | 2,148 | 4.2 (3.9;4.5) | 962 | 4.4 (3.9;4.9) |

| Brown/mixed | 20,536 | 42.6 (41.4;43.7) | 8,620 | 42.0 (40.4;43.6) |

| Native Brazilian Indigenons | 1,763 | 3.4 (3.2;3.9) | 775 | 3.4 (3.0;3.9) |

| Lives with mother | ||||

| No | 5,184 | 10.1 (9.5;10.6) | 2,403 | 10.9 (10.1;11.8) |

| Yes | 39,719 | 89.9 (89.4;90.5) | 16,587 | 89.1 (88.2;89.9) |

| Lives with father | ||||

| No | 7,250 | 36.9 (35.9;37.9) | 7,755 | 39.8 (38.5;41.2) |

| Yes | 7,633 | 63.1 (62.2;64.1) | 1,230 | 60.2 (58.8;61.5) |

| Type of school | ||||

| Public | 5,216 | 85.0 (82.5;87.1) | 14,927 | 84.4 (81.7;86.8) |

| Private | 1,407 | 15.0 (12.9;17.5) | 16,800 | 15.6 (13.2;18.3) |

a) 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

The profile of occurrence of parenting practices according to the adolescent’s role in bullying is shown in Figure 2. When comparing the occurrence of parenting practices between victims and non-victims of bullying, victims showed a lower percentage of positive parental supervision practices (frequent meals with parents, parents knowing about free time activities and checking homework), in relation to those who were not victims of bullying (37.0% versus 42.0%). The same pattern was seen when perpetrators and non-perpetrators (28.0% versus 42.0%) of bullying were assessed. We found that adolescent perpetrators of bullying had lower frequencies of positive parental supervision practices (28.0%) when compared to the other groups-victims (37.0%), non-victims (42.0%), and non-perpetrators (42.0%). The highest percentages of these three practices (42.0%) were found among adolescents who were not victims and were not perpetrators of bullying.

Figure 2 Co-occurrence of parental supervision characteristics according to the role played by the adolescent in bullying, among Brazilian students (n=102,072), National School Student Health Survey (PeNSE), 2015

As shown in Table 3, after adjustment, frequent meals with parents or guardians [ORvictim = 0.86 (95%CI 0.84;0.89); ORperp = 0.85 (95%CI 0.82;0.88)] and parents or legal guardians checking homework [ORvictim = 0.95 (95%CI 0.92;0.97); ORperp = 0.76 (95%CI 0.74;0.78)] showed a statistically significant inverse relationship with bullying victimization and perpetration; that is, adolescents whose parents adopted these parental supervision practices were less likely to be victims and perpetrators of bullying. Parents or legal guardians knowing about school students’ free time activities was only inversely associated with perpetration of bullying [ORperp = 0.70 (95%CI 0.68;0.73)], that is, this practice showed itself to be a protective factor against perpetration of bullying.

Table 3 Crude and adjusted analysis of association between parental supervision and bullying victimization and perpetration, among Brazilian students (n=102,072), National School Student Health Survey (PeNSE), 2015

| Parental supervision characteristics | Victimization due to bullying | Perpetration of bullying | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjustedc | Crude | Adjustedc | |||||

| ORa (95%CIb) | p-valued | ORa (95%CIb) | p-valued | ORa (95%CIb) | p-valued | ORa (95%CIb) | p-valued | |

| Frequently has meals with parents or legal guardians | 0.89 (0.85;0.89) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.84;0.89) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.81;0.87) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.82;0.88) | <0.001 |

| Parents or legal guardians know about school students’ free time activities | 1.04 (1.00;1.09) | 0.035 | 1.02 (0.98;1.06) | 0.260 | 0.70 (0.67;0.73) | <0.001 | 0.70 (0.68;0.73) | <0.001 |

| Parents or legal guardians check homework | 0.95 (0.93;0.98) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.92;0.97) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.73;0.78) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.74;0.78) | <0.001 |

a) OR: Odds ratio; b) 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; c) Adjustment for age, race/skin color, living with mother, living with father, type of school and school shift; d) Wald test for heterogeneity.

Discussion

The results of this study showed a statistically significant inverse association between positive parental supervision practices and bullying behaviors (victimization and perpetration) among Brazilian adolescents. Students who frequently ate meals with their parents or guardians and had their homework checked by them were less likely to suffer and perpetrate bullying. Students whose parents or guardians had knowledge about what they did with their free time were less likely to perpetrate bullying.

Many studies, conducted in high-, middle- and low-income countries between 1990 and 2015, have evaluated the association between parental monitoring/ supervision and adolescent involvement in risk behaviors,16-19 including bullying.7,8,10,20,21 In general, lack of parental monitoring has been shown to be associated with bullying victimization or perpetration. A multicenter study conducted in 83 countries on six different continents between 2003 and 2015 suggests that greater parental involvement and support could facilitate early detection of adolescents’ problematic relationships with their peers. According to the same study, this knowledge would allow parents to help their children solve problems and maintain appropriate and assertive interactions, thus preventing bullying.7 Having a close relationship with parents (parent-child bond) can improve children’s ability to select pro-social friends, which is directly related to reduced involvement in violent situations.22,23

This study found that frequently having meals with a parent or guardian was negatively associated with bullying, similarly to the findings of other studies conducted in the United States in 1996/ 1997 and in Scotland in 2018.24,25 Having family meals together can indicate a parental monitoring practice,8 given that eating meals together provides an opportunity for communication between parents and children, moments to discuss social and emotional issues and, possibly, parental support for children to develop coping strategies in their interpersonal relationships.26 Not only family support, but also support from friends and school could promote adolescent well-being and resilience in response to bullying.25-27

Adolescents whose parents or guardians knew about their free time activities were less likely to perpetrate bullying. Another school-based study, conducted in Turkey in 2005/2006, showed that less parental supervision was a risk factor for bullying perpetration and victimization [OR=1.36 (95%CI 1.05;1.76)].8 In another school-based study conducted in the United States in 1996, Espelage et al. also found similar results, i.e. as time without parental supervision increased, adolescents engaged more in bullying behaviors (β = 0.16; p<0.001) compared to adolescents whose parents knew where and with whom they were.9 In 2005, Gage et al.,28 using data from the United States’ national ‘Health Behaviors of School-Aged Children Survey’, conducted in 2001/ 2002, found that spending at least five nights away from home was associated with frequent involvement in youth violence and aggression. Even if parents or guardians do not know with whom their children are or what they do when they are not under their supervision, there is the possibility that adolescents may use their free time to perpetrate bullying by getting involved with other adolescents who also bully their peers.8

There was negative association between parents or legal guardians checking homework and adolescent involvement in bullying behaviors. Helping children with homework is one of the items that enables measurement of parental support related to school activities, which can be accepted as an indirect measure of parental monitoring.8 Since bullying often occurs at school, parents need to become more involved in issues related to their child’s school environment, and checking homework can be a good start.8 According to Hagan and McCarthy,29 parents who pay attention to their children and monitor them closely, attend to their needs and are available to help them get through difficulties, are key to reducing aggressive behavior at school, including bullying.

It is important to mention that our study brought to light more elements for critical reflection on parental supervision practices and adolescents experiencing bullying. The findings, in addition to increasing understanding of the subject, can be used by public service managers and decision makers in the development and implementation of intersectoral policies (Health and Education) aimed at addressing bullying and, consequently, preventing its negative consequences in this population. It should be noted that, although a new edition of the PeNSE survey was conducted in 2019, the unavailability of related IBGE microdata made it impossible to carry out this study with more recent data.30

This study should be assessed considering its limitations and strengths. Its cross-sectional design can be seen as a limitation: it is not the most appropriate design for the study of causal relationships, in that the exposures (parenting practices) and outcomes (bullying victimization and perpetration) were assessed at the same moment in time, making it difficult to clarify the order of the facts.

Despite the possibility of bidirectionality in the parental supervision-bullying relationship, the literature has shown that parental supervision is more plausible as exposure and the different roles of bullying are more plausible as outcomes.7,8,20,21 In this sense, we stress the importance of conducting longitudinal studies to evaluate this relationship. Another limitation refers to how the events of interest (exposures and outcomes) were measured. Both were evaluated using single questions, referring to the 30 days prior to the survey, which may result in misclassification, since use of single questions tends to lead to underestimation. Future studies, using valid and reliable measuring instruments (bullying - Bullying-Behaviour Scale, Olweus’s Bully/Victim Questionnaire, and Peer Relations Questionnaire; parental practices - Child Feeding Questionnaire, and Parenting Practices Scales) are needed in order to gain greater understanding of these relationships.

Another possible limitation of the study lies in the fact that the sample includes only students enrolled in regular education and present in class on the day of the interview, which may generate selection bias, since adolescents not enrolled in regular education and those absent on the day of the interview are not represented. For example, it is possible that those who were absent are students who most often practice or are most often victims of bullying. On the positive side, the study is based on data from a representative sample of adolescents enrolled in public and private schools from Brazil’s 26 state capitals and Federal District, with a high response rate, which minimizes selection bias as it reduces the possibility of disproportionate/differential losses.

This study indicates that greater parental supervision is inversely associated with bullying behavior in adolescents, both with regard to victimization and perpetration of this type of violence. Monitoring (parents or guardians knowing about their children’s free time activities and checking their homework), greater bonding (frequent meals with parents or guardians) and dialogue between parents and children are characteristics of parental supervision that can facilitate identification of adolescents having conflicting relationships with their peers, so as to contribute to preventing the problem. We also emphasize the importance of creating, in the school environment, measures that strengthen the affective bond between parents and children, allowing for the inclusion of positive, democratic, interactive and nurturing parental supervision practices.

Further studies are needed on parental practices and bullying, in different contexts and with different populations, preferably incorporating more robust instruments to measure these phenomena. Finally, we suggest actions to provide adolescent students with strategies to address bullying be intensified in the school environment.

Referências

1. United Nations Children's Fund. How to talk to your children about bullying: tips for parents [Internet]. United Nations Children's Fund;[New York]; 2021 [cited 2021 ago 02]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/end-violence/how-talk-your-children-about-bullying [ Links ]

2. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying. France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2019. [ Links ]

3. Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, Runions KC. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):602-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007 [ Links ]

4. Silva AN, Marques ES, Peres MFT, Azeredo CM. Trends in verbal bullying, domestic violence, and involvement in fights with frearms among adolescents in Brazilian state capitals from 2009 to 2015. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35(11):e00195118. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00195118 [ Links ]

5. Azeredo CM, Rinaldi AEM, Moraes CL, Levy RB, Menezes PR. School bullying: a systematic review of contextual-level risk factors in observational studies. Aggress Violent Behav. 2015;22:65-76. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.04.006 [ Links ]

6. Álvarez-García D, García T, Núñez JC. Predictors of school bullying perpetration in adolescence: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2015;23:126-36. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.007 [ Links ]

7. Biswas T, Scott JG, Munir K, Thomas HJ, Huda MM, Hasan MM, et al. Global variation in the prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst adolescents: role of peer and parental supports. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;20:100276. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100276 [ Links ]

8. Erginoz E, Alikasifoglu M, Ercan O, Uysal O, Alp Z, Ocak S, et al. The role of parental, school, and peer factors in adolescent bullying involvement: results from the Turkish HBSC 2005/2006 study. Asia-Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP1591-603. doi: 10.1177/1010539512473144 [ Links ]

9. Espelage DL, Bosworth K, Simon TR. Examining the social context of bullying behaviors in early adolescence. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2000;78(3):326-33. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01914.x [ Links ]

10. Alvarenga P, Piccinini C. Práticas educativas maternas e problemas de comportamento em pré-escolares. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2001;14(3):449-60. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722001000300002 [ Links ]

11. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423-78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1 [ Links ]

12. Oliveira WA, Silva JL, Alves Querino R, Santos CB, Ferriani MGC, Santos MA, et al. Revisão sistemática sobre bullying e família: uma análise a partir dos sistemas bioecológicos. Rev Salud Publica. 2018;20(3):396-403. doi: 10.15446/rsap.V20n3.47748 [ Links ]

13. Abramovay M, coordenadora. Conversando sobre violência e convivência nas escolas. Rio de Janeiro: FLACSO; 2012. 83 p. [ Links ]

14. Ministério da Educação (BR). Programa Saúde nas Escolas. Brasília: Ministério da Educação; 2021 [citado 2021 set 26]. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/expansao-da-rede-federal/194-secretarias-112877938/secad-educacao-continuada-223369541/14578-programa-saude-nas-escolas [ Links ]

15. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar 2015. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica, 2016. [citado 2021 ago 02]. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/educacao/9134-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude-do-escolar.html?=&t=o-que-e [ Links ]

16. Barnes GM, Farrell MP. Parental support and control as predictors of adolescent drinking, delinquency, and related problem behaviors. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54(4):763-76. doi: 10.2307/353159 [ Links ]

17. Ewing BA, Osilla KC, Pedersen ER, Hunter SB, Miles JNV, D'Amico EJ. Longitudinal family effects on substance use among an at-risk adolescent sample. Addict Behav. 2015;41:185-91. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.017 [ Links ]

18. Tobler AL, Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM. Relationship between neighborhood context, family management practices and alcohol use among urban, multi-ethnic, young adolescents. Prev Sci. 2009;10(4):313-24. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0133-1 [ Links ]

19. Waizenhofer RN, Buchanan CM, Jackson-Newsom J. Mothers' and fathers' knowledge of adolescents' daily activities: its sources and its links with adolescent adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(2):348-60. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.348 [ Links ]

20. Hong JS, Ryou B, Piquero AR. Do family-level factors associated with bullying perpetration and peer victimization differ by race? comparing European American and African American youth. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35(21-22):4327-49. doi: 10.1177/0886260517714441 [ Links ]

21. Lereya ST, Samara M, Wolke D. Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: a meta-analysis study. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(12):1091-108. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001 [ Links ]

22. Jacobsen T, Hofmann V. Children's attachment representations: longitudinal relations to school behavior and academic competency in middle childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychol. 1997;33(4):703-10. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.703 [ Links ]

23. Smith P, Flay BR, Bell CC, Weissberg RP. The protective influence of parents and peers in violence avoidance among African-American youth. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5(4):245-52. doi: 10.1023/a:1013080822309 [ Links ]

24. Fulkerson JA, Story M, Mellin A, Leffert N, Neumark-Sztainer D, French SA. Family dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: relationships with developmental assets and high-risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):337-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.026 [ Links ]

25. Shaw RJ, Currie DB, Smith GS, Brown J, Smith DJ, Inchley JC. Do social support and eating family meals together play a role in promoting resilience to bullying and cyberbullying in Scottish school children? SSM Popul Health. 2019;9:100485. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100485 [ Links ]

26. Elgar FJ, Craig W, Trites SJ. Family dinners, communication, and mental health in Canadian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):433-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.012 [ Links ]

27. McDonald M, McCormack D, Avdagic E, Hayes L, Phan T, Dakin P. Understanding resilience: similarities and differences in the perceptions of children, parents and practitioners. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;99:270-8. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.016 [ Links ]

28. Gage JC, Overpeck MD, Nansel TR, Kogan MD. Peer activity in the evenings and participation in aggressive and problem behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(6):517. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.012 [ Links ]

29. Hagan J, McCarthy B. Mean streets: youth crime and homelessness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pss, 1997. 320 p. [ Links ]

30. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar. Microdados. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2021 [citado 2021 set 21]. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/educacao/9134-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude-do-escolar.html?edicao=9135&t=microdados [ Links ]

Received: August 31, 2021; Accepted: February 01, 2022

texto en

texto en