Main results

Intimate partner violence was predominant among victims who were young, had a partner, with low schooling, Indigenous, as well as its occurrence being predominant in border regions, at weekends, at night, with use of physical force and the aggressor under the influence of alcohol.

Introduction

Violence is defined as the intentional use of force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, group or community, which may result in injury, death, mental harm, developmental changes or deprivation.1 Its various forms include intimate partner violence (IPV), that is, behavior that occurs in the context of an intimate relationship, resulting in physical, psychological or sexual harm to those involved in the relationship.1 The relationship between the victim of violence and its perpetrator can be current (by a current spouse, partner or boyfriend) or previous (by an ex-spouse, ex-partner or ex-boyfriend).2

Physical violence within relationships affects one in three women at some time in their lives worldwide,3,4 often culminating in the death of the victim. In Brazil, more than 100,000 women were homicide victims between 1980 and 2014, and the Midwest region had the highest mortality coefficients for this cause.5 Despite this statistic including deaths resulting from urban violence and other types of violence, women who have been subject to IPV are more susceptible to death from aggression than those without a history of intrafamily violence.6

Feminicide estimates for the period from 2003 to 2007 indicated that the state of Mato Grosso do Sul had one of the highest female homicide coefficients in Brazil.7 Mato Grosso do Sul has an extensive border area with Bolivia and Paraguay, and a large Indigenous population, which gives it singular cultural characteristics, capable of having an impact on its indicators of violence, as these events are strongly associated with the ways of life of each society.8 Indigenous women are disproportionately marginalized worldwide, making them more exposed to gender-based violence.9 Similarly, women living in border regions are also more vulnerable.10

The objective of this article was to analyze the characteristics of IPV against females aged 20-59, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, between 2009 and 2018.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of IPV against females aged 20 to 59 years, based on the analysis of all cases reported on the Notifiable Health Conditions Information System (Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação - SINAN), in Mato Grosso do Sul between 2009 and 2018.

Mato Grosso do Sul has approximately 2.5 million inhabitants and has the second largest Indigenous population in Brazil, comprising more than 72,000 individuals from eight ethnic groups, distributed among 75 villages located in 29 municipalities.11 Furthermore, 73% of the state’s territorial area is located on the border strip, accounting for 45 of its 79 municipalities. In this study, especially, we considered border municipalities to be only those with city limits bordering with other countries. These account for 11 municipalities, of which five are “twin cities”, i.e., with greater potential for economic and cultural integration between them.12

Participants

The study population comprised all notifications of IPV against females aged 20 to 59 years in the state, recorded on the SINAN system.

Each notification was taken to be a unit of analysis because, due to the characteristics of the database, it was not possible to identify the victims of violence. Thus, there may be just one record or more than one record for the same person in the period assessed.

Cases of IPV were taken to be all notifications with an affirmative answer to at least one of the fields referring to the type of relationship between the aggressor and the victim (spouse; ex-spouse; boyfriend/girlfriend; ex-boyfriend/girlfriend), regardless of the sex of the aggressor (male; female; both sexes; unknown).

Notifications were excluded from the analysis when the place of residence of the victim or the place of occurrence was not within the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, or when it was not possible to identify the place of residence or the place of occurrence.

When calculating the IPV notification rate, the numerator was taken to be the total number of notifications of IPV against females aged 20-59 recorded in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul between 2009 and 2018, while the denominator was the female population living in the state in the same age group (population at risk), as per data from the 2010 Demographic Census, respecting the distribution of each of the categories of the variables analyzed: age group; race/skin color; marital status; schooling; and municipality of residence. The quotient obtained was divided by the total number of years covered by the study (ten years), in order to obtain the average annual notification rate. The results were presented per 100,000 (multiplication factor).

Data sources

The notification data were extracted directly from the SINAN database, made available by the Brazilian National Health System Department of Information Technology (Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde - DATASUS), in June 2020. Population data were retrieved from the database of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE). All the data used in the study are public domain free access data.

Study variables

The outcome of interest in this study were IPV events in which aggression was recorded. To delimit this variable, we considered all IPV notifications with affirmative responses for physical violence, in the field related to the type of violence, whether they were isolated or concomitant with other types of violence (psychological/emotional; neglect/abandonment; sexual; human trafficking; child labor; torture; property; other). The comparison group consisted of all IPV notifications for which there was no record of physical violence, but which had an affirmative response for one or more other types of violence.

The independent variables were those related to the characteristics of the victims, the aggressors and the violent events:

a) Variables related to the characteristics of the victim

- age group (in years: 20-29; 30-39; 40-49; 50-59);

- race/skin color (White; Black; Asian; mixed race; Indigenous);

- marital status (single; married/living together; widowed; separated);

- schooling (no schooling or incomplete elementary education; complete elementary education or incomplete high school education; complete high school education or incomplete higher education; complete higher education); and

- region in which the municipality of residence was located (border with other country; interior region of the state).

b) Variables related to the characteristics of the aggressor

- sex (male; female; both sexes);

- number of aggressors (one; two or more); and

- type of relationship with the victim (spouse; ex-spouse; boyfriend; ex-boyfriend).

c) Variables related to the characteristics of the events

- region in which the municipality where the event occurred was located (border with other country; interior region of the state);

- place of occurrence (residence; shared housing; public thoroughfare; work environment; school; child daycare center; health establishment; socio-educational institution; long-stay institution; prison institution; vacant lot; bar or similar; other; unknown);

- day of the week when event occurred (Sunday; Monday; Tuesday; Wednesday; Thursday; Friday; Saturday);

- time of day when event occurred (morning, 6:00 a.m. to 11:59 a.m.; afternoon, 12:00 p.m. to 17:59 p.m; evening, 18:00 p.m. to 23:59 p.m.; night/early morning, 00:00 a.m. to 05:59h a.m.);

- type of violence (physical; psychological/emotional; sexual; other);

- means used (physical force/beating; threat; sharp object; hanging; blunt object; firearm; hot substance/object; poisoning; other);

- repeated event (yes; no); and

- aggressor under the effect of alcohol (yes; no).

Unknown data were taken to be variables filled in as unknown, or variables with no option filled in (missing).

Statistical methods

Initially, we calculated the notification rates according to the characteristics of the victims. In order to compare the coefficients obtained, we calculated the prevalence ratios (PR) and respective confidence intervals (95%CI) using Poisson regression with robust variance adjustment.

We then performed bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the victim, the aggressor and the circumstances of the event in relation to the type of violence (physical violence; other violence). The differences in the proportions of violent events in relation to the explanatory variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test. Fisher’s exact test was used in cases where the number of observations was less than five. The chi-square test for linear trend was used to analyze the “age group” variable, since it is an ordinal categorical variable. A 5% significance level was adopted for all tests.

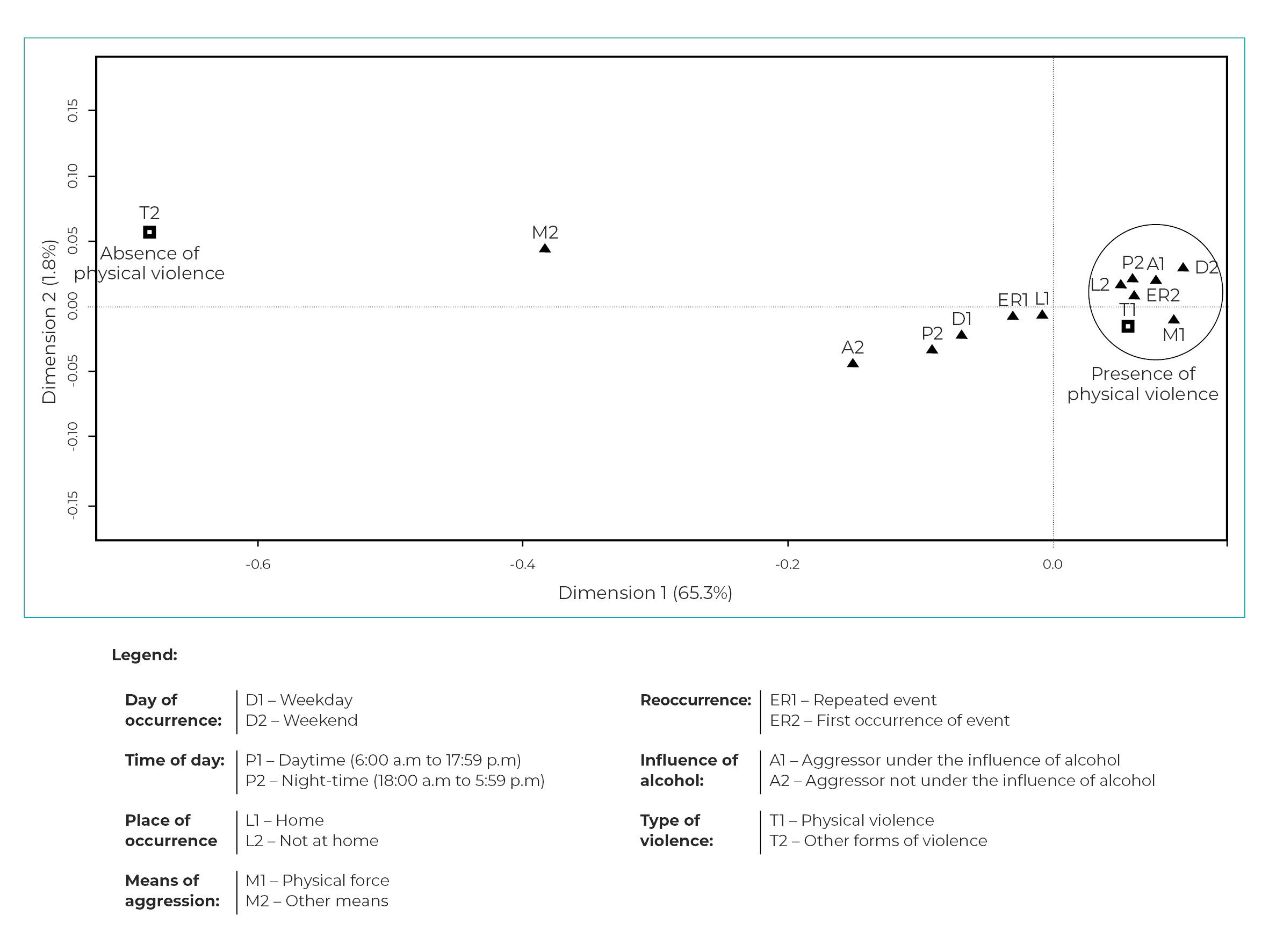

Variables with a p-value < 0.05 underwent multiple correspondence analysis (MCA). MCA is a statistical method that seeks to analyze the existence of distribution patterns of categorical variables13 based on analysis of dependence between rows and columns of contingency tables, seeking to synthesize the variability structure of the data (also called inertia) in a limited number of dimensions (axes). The greater the inertia, the greater the association between row and column.14

This technique makes no assumptions about data distribution. It is non-parametric, which makes it possible to observe various patterns of association, including non-linear patterns. However, the method does not allow inferences for other samples, given its descriptive aspect and the absence of assumptions.

The graph formed by the coordinates of each category, in each dimension or axis, is used to interpret the data. Based on the graph, the existence of clusters and the proximity of categories of variables are assessed to identify patterns of relationships between these characteristics:15 The closer two variables are in the graph, the more frequently they occur together. The graph generates four quadrants, represented by two axes or dimensions. These factors, together, distinguish the characteristics that are allocated to the different quadrants, characterizing groups with opposite profiles. In order to interpret the results, we analyzed the geometric distance between the covariate categories and the presence or absence of physical violence.

The statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.6.3.

Ethical aspects

The data that formed the basis of this study come exclusively from a public domain free access database with no identification of the people in question. For this reason, the research project was exempted from analysis by a Research Ethics Committee, but followed the National Health Council Resolution No. 466, dated December 12, 2012.

Results

Between 2009 and 2018, 64,110 notifications of violence were recorded in Mato Grosso do Sul; 41,986 (65.5%) victims were female. We excluded events that did not occur in Mato Grosso do Sul (n = 93), events the victims of which did not live in Mato Grosso do Sul (n = 13), as well as records that did not allow identification of the state in which the event occurred (n = 590). With regard to the records that remained (n = 22,022), 53.3% of the victims were between 20 and 59 years old, and of these, 9,950 (45.2%) were cases of IPV.

Among the 9,950 notifications analyzed, the percentages of unknown data for the variables studied were: 35.9% for the level of schooling of the victims; 9.7% for the race/skin color of the victims; 8.2% for the marital status of the victims; 1.0% for the sex of the aggressor; 0.1% for the number of aggressors; 23.0% for the time of day at which the event occurred; 16.6% for aggressor under the influence of alcohol; 14.9% for repeated event; and 3.9% for the place the event occurred. Distribution of the percentage of unknown information was similar between victims of physical violence and victims of other types of violence.

Analysis of the notification rate in relation to victims’ characteristics is shown in Table 1. The notification rate decreased as the women’s age increased. IPV was most evident among Indigenous women (488.8/100,000 women/year), this being 5.41 (95%CI 4.98;5.88) times higher than the IPV notification rate among women of White race/skin color.

Table 1 Notifications of intimate partner violence against females aged 20-59, according to victim characteristics, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, 2009-2018

| Variables | Notifications | Population | Mean annual notification rate (per 100,000a) | PRb (95%CIc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (in years) | ||||

| 20-29 | 4,122 | 217,847 | 189.2 | 1.00 |

| 30-39 | 3,384 | 193,512 | 174.9 | 0.92 (0.88;0.97) |

| 40-49 | 1,763 | 164,890 | 106.9 | 0.57 (0.53;0.60) |

| 50-59 | 681 | 117,203 | 58.1 | 0.31 (0.28;0.33) |

| Race/skin color | ||||

| White | 3,016 | 333,946 | 90.3 | 1.00 |

| Black | 694 | 34,759 | 199.7 | 2.21 (2.03;2.40) |

| Asian | 138 | 9,206 | 149.9 | 1.66 (1.39;1.96) |

| Mixed race | 4,447 | 301,433 | 147.5 | 1.63 (1.56;1.71) |

| Indigenous | 689 | 14,096 | 488.8 | 5.41 (4.98;5.88) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 2,152 | 318,767 | 67.5 | 1.00 |

| Married/living together | 5,909 | 291,526 | 202.7 | 3.00 (2.86;3.15) |

| Widowed | 51 | 24,453 | 20.9 | 0.31 (0.23;0.40) |

| Separated | 1,026 | 58,706 | 174.8 | 2.59 (2.40;2.79) |

| Schooling | ||||

| No schooling or incomplete elementary education | 3,220 | 271,420 | 118.6 | 1.00 |

| Complete elementary education or incomplete high school education | 1,577 | 112,966 | 139.6 | 1.18 (1.11;1.25) |

| Complete high school education or incomplete higher education | 1,368 | 207,469 | 65.9 | 0.56 (0.52;0.59) |

| Complete higher education | 218 | 100,189 | 21.8 | 0.18 (0.16;0.21) |

| Municipality of residence | ||||

| Interior region of the state | 8,238 | 616,698 | 133.6 | 1.00 |

| Border with other country | 1,712 | 76,754 | 223.1 | 1.65 (1.56;1.73) |

| Total | 9,950 | 693,452 | 143.5 | |

a) In order to calculate the notification rate, we took the female population aged 20-59, taking the 201 Demographic Census as our reference; b) PR: Prevalence ratio; c) 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

IPV notification rates were higher for women who had partners (married or living together) and who were separated, i.e. 3.00 (95%CI 2.86;3.15) and 2.59 (95%CI 2.40;2.79) times the rates found for single women (reference), respectively. The highest IPV notification rates were found for women with complete elementary education or incomplete high school education, followed by women with no schooling or incomplete elementary education. IPV notification rates for women living in border municipalities were 1.65 (95%CI 1.56;1.73) time higher than the IPV notification rate for those living in other municipalities in the state.

Among the 9,950 IPV notifications, 9,131 (91.8%) recorded physical violence. The proportional distribution of IPV events according to the characteristics of victims and aggressors regarding physical aggression is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Characteristics of intimate partner violence victims and aggressors, by type of violence, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, 2009-2018

| Variables | Physical violence (n = 9,131) | Other forms of violence (n = 819) | Total (n = 9,950) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age group (in years) | |||||||

| 20-29 | 3,869 | 42.4 | 253 | 30.9 | 4,122 | 41.4 | < 0.001a |

| 30-39 | 3,109 | 34.1 | 275 | 33.5 | 3,384 | 34.0 | |

| 40-49 | 1,574 | 17.2 | 189 | 23.1 | 1,763 | 17.8 | |

| 50-59 | 579 | 6.3 | 102 | 12.5 | 681 | 6.8 | |

| Race/skin color | |||||||

| White | 2,784 | 30.5 | 232 | 28.3 | 3,016 | 30.3 | < 0.001b |

| Black | 624 | 6.8 | 70 | 8.5 | 694 | 7.0 | |

| Asian | 133 | 1.5 | 5 | 0.6 | 138 | 1.4 | |

| Mixed race | 4,037 | 44.2 | 410 | 50.1 | 4,447 | 44.7 | |

| Indigenous | 681 | 7.5 | 8 | 1.0 | 689 | 6.9 | |

| Unknown | 872 | 9.5 | 94 | 11.5 | 966 | 9.7 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 1,915 | 21.0 | 237 | 28.9 | 2,152 | 21.6 | < 0.001b |

| Married/living together | 5,481 | 60.0 | 428 | 52.3 | 5,909 | 59.4 | |

| Widowed | 47 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 51 | 0.5 | |

| Separated | 925 | 10.1 | 101 | 12.3 | 1,026 | 10.3 | |

| Unknown | 763 | 8.4 | 49 | 6.0 | 812 | 8.2 | |

| Schooling | |||||||

| No schooling or incomplete elementary education | 2,967 | 32.5 | 253 | 30.9 | 3,220 | 32.4 | < 0.001b |

| Complete elementary education or incomplete high school education | 1,469 | 16.1 | 108 | 13.2 | 1,577 | 15.8 | |

| Complete high school education or incomplete higher education | 1,212 | 13.3 | 156 | 19.0 | 1,368 | 13.7 | |

| Complete higher education | 178 | 1.9 | 40 | 4.9 | 218 | 2.2 | |

| Unknown | 3,305 | 36.2 | 262 | 32.0 | 3,567 | 35.9 | |

| Municipality of residence | |||||||

| Border with other country | 1,313 | 14.4 | 399 | 48.7 | 1,712 | 17.2 | < 0.001b |

| Interior region of the state | 7,818 | 85.6 | 420 | 51.3 | 8,238 | 82.8 | |

| Sex of the aggressor | |||||||

| Male | 8,719 | 95.5 | 692 | 84.5 | 9,411 | 94.6 | < 0.001b |

| Female | 187 | 2.0 | 45 | 5.5 | 232 | 2.3 | |

| Both sexes | 136 | 1.5 | 70 | 8.5 | 206 | 2.1 | |

| Unknown | 89 | 1.0 | 12 | 1.5 | 101 | 1.0 | |

| Number of aggressors | |||||||

| One | 7,799 | 85.4 | 687 | 83.9 | 8,486 | 85.3 | 0.220b |

| Two or more | 1,232 | 13.5 | 123 | 15.0 | 1,355 | 13.6 | |

| Unknown | 100 | 1.1 | 9 | 1.1 | 109 | 1.1 | |

| Type of relationship with the victimc | |||||||

| Spouse | 6,453 | 70.7 | 502 | 61.3 | 6,955 | 69.9 | < 0.001b |

| Ex-spouse | 1,825 | 20.0 | 268 | 32.7 | 2,093 | 21.0 | |

| Boyfriend | 568 | 6.2 | 15 | 1.8 | 583 | 5.9 | |

| Ex-boyfriend | 313 | 3.4 | 39 | 4.8 | 352 | 3.5 | 0.034b |

a) Chi-square linear trend test; b) Pearson’s chi-square test; c) Multiple answers were possible for this variable, resulting in percentages above 100%.

The 20-39 age group accounted for the majority of notifications of IPV (n = 7,506; 75.4%) and physical violence (n = 6,978; 76.4%). The highest proportions of both IPV (n = 3,220; 32.4%) and physical violence (n = 2,967; 32.5%) occurred among women with lower schooling and who had a partner (IPV, n = 5,909; 59.4%; physical violence, n = 5,481; 60.0%). The IPV notification rate was higher in the border municipalities. In turn, the proportion of physical violence was higher in municipalities in the interior region of the state (n = 7,818; 85.6%). Analysis of the notifications showed that the aggressors were mostly male (n = 9,411; 94.6%), spouses (n = 6,955; 69.9%) or ex-spouses (n = 2,093; 21.0%) of the victim, and that they acted alone (n = 8,486; 85.3%).

Table 3 shows the proportional distribution of notified IPV events, according to their characteristics and according to the presence or absence of physical violence. Physical violence was the predominant type of violence found in the notifications, even though it occurred simultaneously with other forms of violence in 42.8% of cases. There was predominance of physical violence in the municipalities in the interior region of the state when compared to municipalities located in border regions. Most of all the recorded events occurred at the victims’ homes; however, physical violence was higher in events that occurred on public thoroughfares, in bars or similar environments. The events occurred mainly at the weekend (Saturdays and Sundays) and at night, both for IPV events and for events in which physical violence occurred. The means most often used was physical force. Repeated events and the use of alcohol by the aggressor stood out.

Table 3 Characteristics of intimate partner violence events, by type of violence, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, 2009-2018

| Variables | Physical violence (n = 9,131) | Other forms of violence (n = 819) | Total (n = 9,950) | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Municipality where violence occurred | |||||||

| Interior region of the state | 7,818 | 85.6 | 420 | 51.3 | 8,238 | 82.8 | < 0.001a |

| Border with other country | 1,313 | 14.4 | 399 | 48.7 | 1,712 | 17.2 | |

| Place where violence occurred | |||||||

| Home | 7,367 | 80.7 | 681 | 83.2 | 8,048 | 80.9 | < 0.001a |

| Public thoroughfare | 792 | 8.7 | 49 | 6.0 | 841 | 8.5 | |

| Bar or similar place | 207 | 2.3 | 5 | 0.6 | 212 | 2.1 | |

| Other | 404 | 4.4 | 61 | 7.4 | 465 | 4.7 | |

| Unknown | 361 | 3.9 | 23 | 2.8 | 384 | 3.8 | |

| Day of the week | |||||||

| Monday | 1,249 | 13.7 | 121 | 14.8 | 1,370 | 13.8 | < 0.001a |

| Tuesday | 996 | 10.9 | 151 | 18.4 | 1,147 | 11.5 | |

| Wednesday | 979 | 10.7 | 121 | 14.8 | 1,100 | 11.1 | |

| Thursday | 1,015 | 11.1 | 158 | 19.3 | 1,173 | 11.8 | |

| Friday | 1,049 | 11.5 | 119 | 14.5 | 1,168 | 11.7 | |

| Saturday | 1,689 | 18.5 | 72 | 8.8 | 1,761 | 17.7 | |

| Sunday | 2,154 | 23.6 | 77 | 9.4 | 2,231 | 22.4 | |

| Time of day | |||||||

| Morning - 6:00 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | 1,002 | 11.0 | 168 | 20.5 | 1,170 | 11.8 | < 0.001a |

| Afternoon - 12:00 p.m. to 17:59 p.m. | 1,585 | 17.4 | 139 | 17.0 | 1,724 | 17.3 | |

| Evening - 18:00 p.m. to 23:59 p.m. | 3,346 | 36.6 | 211 | 25.8 | 3,557 | 35.8 | |

| Night/early morning - 00:00 a.m. to 05:59 a.m. | 1,152 | 12.6 | 56 | 6.8 | 1,208 | 12.1 | |

| Unknown | 2,046 | 22.4 | 245 | 29.9 | 2,291 | 23.0 | |

| Type of violenceb | |||||||

| Physical | 9,131 | 100.0 | - | - | 9,131 | 91.8 | < 0.001c |

| Psychological/emotional | 3,196 | 35.0 | 625 | 76.3 | 3,821 | 38.4 | |

| Sexual | 117 | 1.3 | 59 | 7.2 | 176 | 1.8 | |

| Other | 596 | 6.5 | 207 | 25.3 | 803 | 8.1 | |

| Means usedc | |||||||

| Physical force/beating | 7,810 | 85.5 | 52 | 6.4 | 7,862 | 79.0 | < 0.001c |

| Threats | 1,543 | 16.9 | 388 | 47.4 | 1,931 | 19.4 | |

| Sharp object | 1,107 | 12.1 | 13 | 1.6 | 1,120 | 11.7 | |

| Hanging | 818 | 9.0 | 8 | 1.0 | 826 | 8.3 | |

| Blunt object | 672 | 7.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 674 | 6.8 | |

| Firearm | 95 | 1.0 | 11 | 1.3 | 106 | 1.1 | 0.420c |

| Hot substance/object | 56 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 | 61 | 0.6 | 0.990c |

| Poisoning | 25 | 0.3 | 18 | 2.2 | 43 | 0.4 | < 0.001c |

| Other | 335 | 3.7 | 117 | 14.3 | 452 | 4.5 | |

| Repeated event | |||||||

| Yes | 5,124 | 56.1 | 567 | 69.2 | 5,691 | 57.2 | < 0.001a |

| No | 2,654 | 29.1 | 118 | 14.4 | 2,772 | 27.9 | |

| Unknown | 1,353 | 14.8 | 134 | 16.4 | 1,487 | 14.9 | |

| Aggressor under the effect of alcohol | |||||||

| Yes | 5,424 | 59.4 | 289 | 35.3 | 5,713 | 57.4 | < 0.001a |

| No | 2,219 | 24.3 | 370 | 45.2 | 2,589 | 26.0 | |

| Unknown | 1,488 | 16.3 | 160 | 19.5 | 1,648 | 16.6 | |

a) Pearson’s chi-square test; b) Multiple answers were possible for this variable, resulting in percentages above 100%; c) Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 1 shows the MCA according to the characteristics of those involved in IPV events and the type of violence. The MCA explained 67.4% of the data variability. In relation to the type of violence, we found that the point related to physical violence was close to the points related to victims belonging to younger age groups (20 to 49 years), of non-Indigenous race/skin color, with lower schooling (ranging from illiterate to those with incomplete elementary education), victims who had a partner, and those living in the interior region of the state. With regard to the aggressor, association was found between the point related to physical violence and the points related to the current (male) partner.

Note: Proximity between two categories of variables can be interpreted as proximity between groups of individuals, so that the closer the points are to each other, the greater the similarity of the patterns of occurrence between the individuals; conversely, the more distant they are, the greater the dissimilarity between them.

Figure 1 Perceptual map of victim and aggressor characteristics for the first two dimensions in relation to the “type of violence” outcome, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, 2009-2018

No distribution pattern was found for the variables in relation to the other types of violence. This distribution pattern on the two-dimensional plane confirms the pattern found in the bivariate analysis, with the exception of the race/skin color variable, which, in the bivariate distribution, highlighted the Indigenous population with regard to physical violence. On the two-dimensional plane, the MCA did not show a well-defined profile based on the variables analyzed, since the point related to this variable was not close to any of the categories analyzed in relation to type of violence (physical; other form of violence). As such the MCA did not enable a pattern of association between Indigenous race/skin color and type of violence to be established.

The results of the MCA according to the characteristics of the circumstances of the IPV events are shown in Figure 2. On the two-dimensional plane, we found that physical violence occurred at the weekend, at night, away from the victim’s home, in events occurring for the first time, with use of physical force, perpetrated by intimate partners under the influence of alcohol. Based on the variables we analyzed, it was not possible to find a typical pattern that could characterize the other forms of violence. Only the point related to the use of physical force as a means of aggression came close. The MCA regarding IPV circumstances and characteristics showed similarity with the bivariate analysis of the same variables, resulting in an inertia value of 67.3%.

Note: Proximity between two categories of variables can be interpreted as proximity between groups of individuals, so that the closer the points are to each other, the greater the similarity of the patterns of occurrence between the individuals; conversely, the more distant they are, the greater the dissimilarity between them.

Figure 2 Perceptual map of event characteristics for the first two dimensions in relation to the “type of violence” outcome, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, 2009-2018

Discussion

The analysis showed that IPV was associated with women’s age, being between 20 and 29 years old, having lower levels of schooling, having a partner, being of Indigenous race/skin color and living in a border municipality. The aggressors were mostly current partners of the victims and male. The events occurred primarily at the home of the victims, at the weekend, at night, with the use of physical force and under the influence of alcohol, and mainly in the interior region of the state. These characteristics revealed regional peculiarities of IPV, especially regarding specific groups, such as Indigenous women.

Of the total notifications of violence against adult women, 45.2% corresponded to IPV. This percentage was lower than that recorded in Brazil16 as a whole between 2011 and 2017 (62.4%), and in the state of Rio Grande do Sul17 between 2010 and 2014 (52.2%). This finding is believed to be the result of the frequent invisibility of violence committed in the domestic environment by men against women,18 rooted in the machista culture, which is more evident in Mato Grosso do Sul, a state where it is still dominant, compared to the rest of the country,19 which leads many women not to report their partner as being responsible for the violence they suffer.

Our analysis of the notifications revealed a profile of IPV victims coinciding with that described in the literature, with emphasis on young women,20-23 with a partner21 and reporting low levels of schooling.21,22

Contrary to what has been reported in previous studies, which showed a higher frequency of violence against Black20,22 and White24 women, our analysis showed a higher frequency of notifications of violence and a higher proportion of physical violence against women of Indigenous race/skin color. Indigenous women account for some 2.0% of the female population of Mato Grosso do Sul, in the 20-59 age group, according to the 2010 Census; however, these women accounted for 6.9% of IPV notifications and 7.5% of physical violence notifications. A previous study also indicated that Indigenous women are among the most victimized by gender-based violence.25 These findings, therefore, highlight a characteristic peculiar to Mato Grosso do Sul, where there is a notable presence of Indigenous people.

Violence among Indigenous people is strongly associated with the process of loss of their lands and their consequent confinement to reservations, forcing them to change their ways of life and making it necessary for men and women to seek their sustenance outside their villages.25 In Mato Grosso do Sul, gender relations between the Indigenous have been influenced by contact with non-Indigenous people, the reduction of rituals and shamanistic practices, the introduction of alcoholic beverages and drugs, resulting in their changing and often becoming conflictive and violent.25 In addition, as in other parts of the world, Indigenous peoples are subjected to various deprivations, even more so among women, resulting in marginalization, discrimination and lack of access to resources, which makes them more vulnerable to gender-based violence when compared to women of other races/skin colors.9

The IPV notification rate was higher in municipalities bordering Paraguay and Bolivia, reiterating the problem of violence against women in border areas indicated by a previous study.10 The proportion of physical violence, however, was higher in the interior region of the state than in the border municipalities. This finding may be associated with underestimation of IPV events in border municipalities, usually resulting from situations in which there are no reports or evidence of physical violence.

The characteristics of the aggressors were also similar to those reported in the literature, whereby males17,20 and the victims’ current partners16,23 were predominant. On the other hand, a study carried out with data from the Pará State Court of Justice indicated the victim’s ex-partner as having committed violence in 56.7% of cases.26 It is assumed, however, that this difference is related to protective measures being ordered in the cases that reach the judicial system.

The characteristics of the events reported were similar to those found in the literature, occurring predominantly at the victims’ homes,16,20,22,26 at weekends and at night,26 both in relation to all types of intimate partner violence and also in relation to physical violence.

Population-based surveys have shown that the most common type of IPV is psychological violence, followed by physical and sexual violence.2,16 Studies that investigate notifications, however, are based on care provided in health services, usually in response to physical and/or sexual violence, in which cases of physical violence prevail.16,17

The aggressions against women occurred concomitantly with psychological violence, sexual violence and other types of violence, demonstrating the frequent overlapping of the various types of violence, as already described in the literature.2 Similar to other studies, the most commonly used means was physical force,20,24,26 and repeated events were identified in the majority of the records.26 In our study, physical violence was more evident in events that occurred for the first time, and may be related to the worsening of previous situations, leading to the victim reporting it.

Alcohol is one of the main triggers of intimate partner violence.23,27 Alcohol consumption by the aggressor was reported by most of the IPV victims and accounted for a higher proportion among the events in which there was physical violence, compared to cases in which the victim stated that the aggressor had not drunk alcohol. There is consensus in the literature that alcohol intake by men, present in most cases of IPV, is associated with aggressive situations, in greater or lesser proportions, acting as a trigger for violent events or worsening them.27

Despite the fact that most of the characteristics analyzed by us, regarding the victim, the aggressor and the event, have already been well described in the literature, our study contributes to highlighting, through bivariate analysis, violence against Indigenous women in Mato Grosso do Sul, bolstering the indicators that Indigenous women are more subject to violence than the rest of the population.9

Analyzing notifications of cases of IPV, based on data from the SINAN, proved to be a useful tool for studying the epidemiological characteristics of these events in the population, even in the face of the data input errors found in this study.

The increasing number of events recorded may represent not only an increase in the number of occurrences in the population, but also greater awareness on the part of health professionals as to the need to record them, giving them greater visibility and requiring greater emphasis on addressing them.

It is known that notifications represent only a portion of the total of violent events occurring in the population, since they arise from use of health services28 and their being recorded depends on the sensitivity of health professionals.2 Furthermore, added to the difficulties women have in externalizing the violence they experience,29 identification of cases by health professionals is limited.30

Moreover, the limitations of this study are due especially to the fact that the events we analyzed are based on secondary data from various health services, and it is not possible to guarantee standardization of form filling, nor to correct shortcomings in data recording. It is known that notifications account for just part of total occurrences, so that the characteristics we found may differ from those existing in events as a whole in the population. Furthermore, as notifications are secondary data, it is not possible to extrapolate the findings of this study, given the possibility of selection bias and in view of the possibility of variations in the frequency of events of violence being reported in certain groups and places.

As a conclusion, we point to the need to sensitize health professionals responsible for providing care to women, at all levels of health care, in order for public health services to be more prepared to identify signs of intimate partner violence, preferably before they culminate in physical violence. Finally, it is the responsibility of those in charge of health services to provide continuing training, especially for the adequate and complete recording of violent events, thus enabling generation of reliable evidence to support epidemiological studies and the formulation of effective public policies.

texto em

texto em