INTRODUCTION

Diarrheal disease is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among infants, young children and the elderly throughout the world. Worldwide, it has been estimated about 3-5 billion of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) cases per year and about 1.4-2.5 million deaths gastroenteritis related disease annually1,2. It is estimated that about 30-40% of diarrheal cases remain unknown etiology although more sensitive molecular methods are available3,4.

Several enteric pathogens, viruses, bacteria and protozoa have been associated with AGE cases1. Many viral pathogens, rotaviruses (RVs), noroviruses (NoVs), astroviruses (AstVs), and enteric adenoviruses (AdVs) have been recognized as the major enteropathogens of gastroenteritis in children3,5. Toroviruses6, bocaviruses7, picobirnaviruses8 and a few picornaviruses9 (non-polio enteroviruses10,11,12 - NPEV), parechoviruses13, aichiviruses14, cosaviruses15 and sali/klasseviruses16 have also been found to be associated with AGE.

Currently, the genus Enterovirus contains four species of enterovirus (EV) affecting humans (EV-A to D) comprising more than 100 serotypes17.

EV are non-enveloped RNA viruses belonging to the family Picornaviridae and infect billions of people worldwide and cause a variety of clinical diseases such as poliomyelitis, myocarditis, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, respiratory illnesses, conjunctivitis, hand-foot and mouth diseases and other acute and chronic illnesses18,19.

In Brazil, there are few studies that show the detection or relationship between EV and AGE20,21,22 and no molecular epidemiologic studies about diarrheal diseases and the prevalence of non-polio EV are available.

Several studies have shown the association of EV with AGE and the objective of this preliminary study was to describe the prevalence of EV in stool samples collected from children with AGE in Belém, Pará State, Brazil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

FECAL SPECIMENS

Patients included children who were hospitalized for AGE and presented diarrhea, which was defined as ≥ 3 loose, watery or semi-liquid stools in a 24 h period and met the World Health Organization's standard case definitions. All fecal samples were collected and sent to the Instituto Evandro Chagas (IEC) where they were stored at -20° C until processing.

All samples were collected from children < 5 years old who were admitted to a large paediatric hospital in the City of Belém, with acute diarrhea during May 2010-April 2011.

Of a set of 798 fecal samples collected, 176 representative samples were selected each month randomly, using the random (non-replacement) statistic tool of the BioEstat v.5.0 software package23 and screened by real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) for EV.

The study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee in Humans of the IEC under number 06312512.6.0000.0019.

RNA VIRAL EXTRACTION

Viral RNA was extracted from 300 µL of a 20% fecal suspension in PBS by automatic extraction using a QIAcube and the QIAamp® Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) preceded by manual lysis, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

DIRECT DETECTION OF EV GENOME BY RRT-PCR AND SEMI-NESTED RT-PCR

EV detection was performed by rRT-PCR assay, as described by Kilpatrick et al24 using a primer pair and probe that amplifies a fragment within the 5'NCR. Samples were screened by using the AgPath-IDTM One-Step RT-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) on Applied Biosystems 7500 platform. Reverse transcription was performed at 45° C for 10 min, followed by inactivation of reverse transcriptase at 95° C for 10 min. PCR cycling conditions included 45 cycles of denaturation at 95° C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60° C for 1 min.

Semi-nested RT-PCR for EV was performed using SuperScript® III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) to confirm all RNA samples showing Ct values greater than 35. Briefly, the reaction was performed with 5 µL of RNA extract (1:5 diluted), 12.5 µL reaction mix, 0.4 µmol/L primer P1 (5'-CAAGCACTTCTGTTTCCCCGG-3') and P3 (5'-ATTGTCACCATAAGCAGCCA-3')25, 1 µL SuperScriptTM III RT/Platinum® Taq Mix enzymes and autoclaved distilled water to 25 µL. The second-round of PCR was performed with 2 µL of first-round PCR product, 0.4 µmol/L of primer P2 (5'-TCCTCCGGCCCCTGAATGCG-3')25 and primer P3 using Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the first round reactions were incubated at 45° C for 20 min and then 95° C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95° C for 30 s, 59° C for 30 s and 72° C for 1 min. The second round was performed under the same cycling conditions in a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The reaction targeting the conserved 5' NCR amplifies a fragment of approximately 440 bp and 155 bp respectively. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels containing SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain and compared to a 50 bp DNA Ladder (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) by visualization with an UV transilluminator.

RESULTS

In order to assess the relevance of EV in children with acute diarrhea, a rRT-PCR assay was performed targeting the conserved 5' NCR of the EV genome.

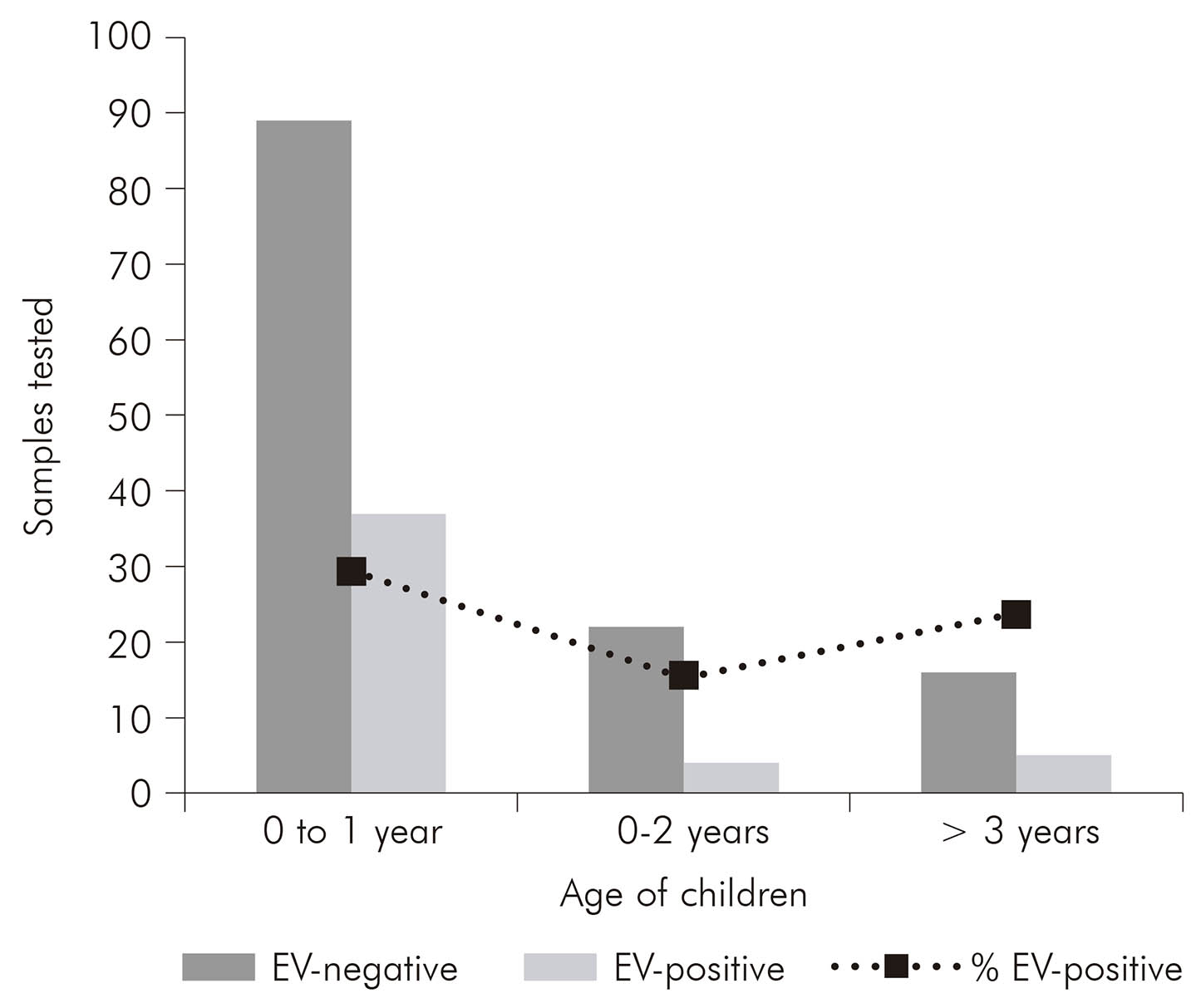

Of the 176 diarrheic samples tested, 29.4% (37 samples), 15.4% (four samples) and 23.8% (five samples) were positive for EV to 0-1 year, 1-2 years and > 3 years respectively (Figure 1). Of these, 46 (26.1%) were positive by rRT-PCR including samples subjected to semi-nested RT-PCR for confirmation. The results showed that was possible to detect EV with the same efficiency in both assays for all tested samples.

DISCUSSION

AGE is a very common disease causing diarrhea worldwide and several studies have reported significant role of RV, NoV and AdV in children as etiologic agent26,27,28,29,30.

Currently, several reports highlighting NPEV as one of the viral etiologies of AGE have been also documented31,32,33.

Rao et al33, in 2013, showed a high frequency (19%) of NPEV associated with acute diarrhea in children, suggesting a significant association between NPEV and diarrheal disease. In 2014, Rao et al2 showed that NPEV was the main infectious agent detected in children with persistent diarrhea and a significant association of NPEV with acute diarrhea.

In a case control study in 2015, Patil et al12 observed that NPEV was detected in 13.7% in children with acute diarrhea contrasting significantly with 4.9% in non-diarrheic ones.

The current study has detected a high prevalence (26.1%) of NPEV in diarrheic samples though we have not tested the stool samples for other viral pathogens. Although our preliminary results show a high circulation and a possible association of EV with acute diarrheic disease among children under 5 years old, additional studies are warranted to better assess this association, taking into account that some points need to be better investigated like genotype, possible mixed infection with other pathogens and asymptomatic shedding by healthy children.

All positive stool samples will be inoculated on cell cultures and additional molecular studies will be conducted to genotype all detected EV.