Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Pan-Amazônica de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 2176-6215versão On-line ISSN 2176-6223

Rev Pan-Amaz Saude vol.11 Ananindeua 2020 Epub 04-Ago-2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s2176-6223202000245

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Acute Chagas disease in Pará State, Brazil: historical series of clinical and epidemiological aspects in three municipalities, from 2007 to 2015

1 Universidade do Estado do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brasil

2 Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brasil

3 Centro Universitário do Estado do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brasil

4 Instituto Evandro Chagas, Ananindeua, Pará, Brasil

5 Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, Belém, Pará, Brasil

OBJECTIVE:

To analyze the clinical and epidemiological profile of acute Chagas disease in the municipalities of Belém, Abaetetuba, and Breves, Pará State, Brazil, from 2007 to 2015.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A total of 696 cases were analyzed, using data from the Information on Notifiable Diseases, and statistical tests were applied using the BioEstat software.

RESULTS:

Of the 696 investigated, 35.63% were from Abaetetuba, 40.66% from Belém and 23.71% from Breves. The most prevalent age group was 30-59 years, being 35.89% in Abaetetuba and 53.71% in Belém; in contrast, in Breves, 32.73% were between 0 and 14 years old. Affected men represented 51.61% in Abaetetuba, 49.47% in Belém, and 56.36% in Breves. The urban area registered 56.45% of the cases in Abaetetuba and 96.11% in Belém; and in the rural area of Breves 66.06% of cases. The mortality rate was 1.49%. The oral transmission (82.33%) was predominant. Fever and asthenia were present in over 75% of records. The epidemic curve of seasonality was higher between July and November, and the incidence was more expressive in Breves, with two epidemic waves: one in 2009 (27.98/100,000 inhabitants) and another in 2015 (63.38/100,000 inhabitants).

CONCLUSION:

The epidemiological relevance of acute Chagas disease and its importance for public health are justified by the epidemic potential of the parasite, which requires the organization of health services, activities for the prevention and control of the disease.

Keywords: Chagas Disease; Descriptive Epidemiology; Neglected Diseases; Health Indicator

INTRODUCTION

After more than a century of the discovery of Chagas disease (CD) by Carlos Chagas (1909), this pathology still represents one of the most important neglected diseases in the world1. CD is an anthropozoonosis caused by the flagellate protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, which is transmitted to man by the feces of vector insects, mainly of the genera Triatoma, Panstrongylus and Rhodnius2. Transmission also occurs through transfusion, transplacental and oral routes3.

It is estimated that 65 million people live at risk of infection in endemic countries of the Americas, with 12,000 people infected annually4. Between 2003 and 2018, 4,556 cases of acute CD (ACD) were reported in Brazil. Until 2007, the majority cases occurred in the Northeast Region; however, from the finding of oral transmission3, this scenario has changed with the Northern Region had the highest incidence rates5.

CD is considered endemic in the Amazon Region with frequent epidemic outbreaks among members of the same family, occurring in urban and rural areas6,7,8. From 2006 to 2014, the state of Pará recorded 884 cases of the that disease and, 25.7% (227) were from the Metropolitan Region of Belém and 21.1% (187) from Abaetetuba; 26.9% (238) were registered in the Marajó island, of which 44.5% (106) cases were from Breves4.

In Pará, new acute cases have been increasingly reported which is why epidemiological surveillance services are increasingly on alert with continuous attention in populations at higher risk and, above all, encouraging professionals who work in health care, so that new cases can be diagnosed and treated even more quickly, trying to improve this scenario that has often disabling outcomes if there is no effective and immediate care9.

CD presents a biphasic clinical course composed of an acute phase, sometimes unidentified, evolving to the chronic phase. It is considered an acute phase when the individual has persistent fever (for more than seven days), with or without edema of the face or limbs, exanthema, adenomegaly, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, acute heart disease (tachycardia, signs of heart failure), hemorrhagic manifestations, jaundice, Romaña's sign or inoculation chagoma10.

The epidemic potential of CD in Pará justifies the importance of population-based epidemiological studies that can help in the strategic planning of health surveillance activities aimed at controlling the disease. This study aimed to describe the clinical and epidemiological profile of patients with CD in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves in the Pará State.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective cross-sectional study based on secondary data collected from the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) of the Ministry of Health (MS)11. 696 cases of ADC had been investigated in this study with laboratory and/or epidemiologic confirmation, living in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, from 2007 to 2015.

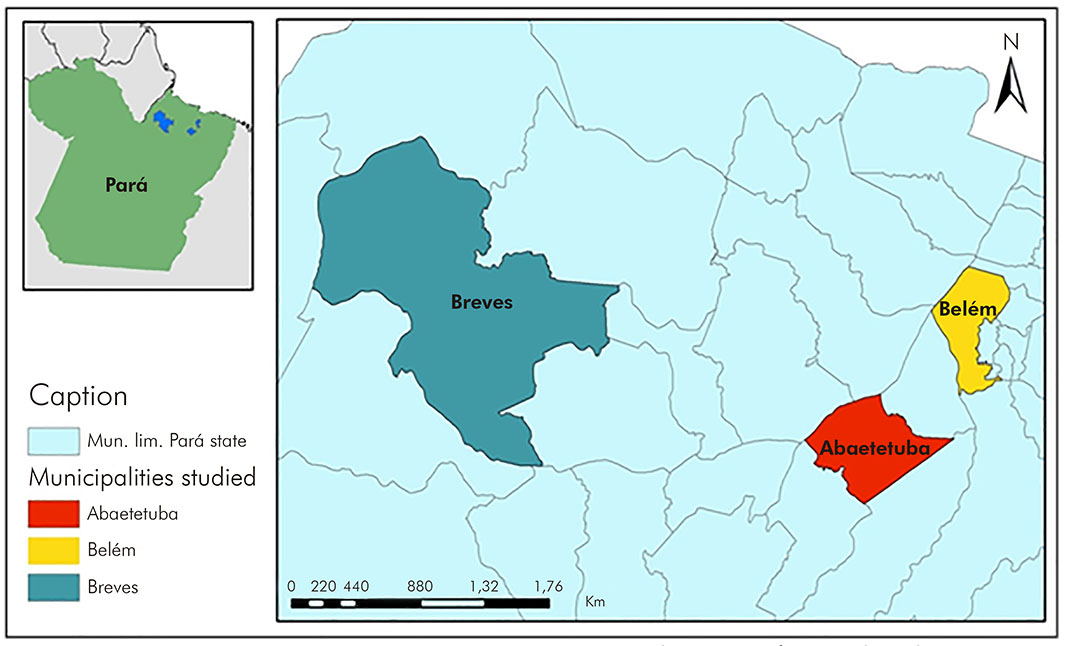

The municipality of Abaetetuba is located in the northeast of Pará (Latitude 01º43'05" South; Longitude 48º52'57" West) and had ± 153,380 inhabitants in 2017; Belém, capital of the State (Latitude: 1º27'18" South; Longitude: 48º30'9" West), had an estimated population ± 1,452,275 inhabitants in the same year; and Breves, considered the largest archipelago of Marajó, had ± 99,896 inhabitants also in that year12 (Figure 1).

Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, 2015.

Figure 1 - Geographic location of the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, Pará State, Brazil

The following variables were analyzed: i) epidemiological profile: municipality and area of residence, sex, age group, race/skin color, schooling, month and year of diagnosis/notification, confirmation criterion, disease progression, possible mode of transmission, treatment for asymptomatic and symptomatic cases and laboratory diagnosis (thick blood smear, Strout test/microhematocrit technique and Quantitative Buffy Coat); ii) clinical profile: face/limbs edema, meningoencephalitis, polyadenopathy, persistent fever, hepatomegaly, signs of congestive heart failure (CHF), asthenia, splenomegaly and inoculation chagoma/Romaña's sign.

The crude incidence rates were calculated and standardized per world population and presented per 100,000 inhabitants. In order to seasonality, the reported and confirmed cases were counted and grouped by the month of the date of the first symptoms, considering the 12 months of the years of the studied series, using the Excel's logic function. Seasonality in the time series was eased by the simple moving average. For the inferential statistical analysis, the chi-square test of adherence of equal and expected proportions was applied for the analysis of frequency distribution using the BioEstat v5.0 software13. Data were presented in tables and graphs used Microsoft Excel 2013.

RESULTS

Of the 696 cases of ACD investigated, 40.66% (283/696) lived in Belém, 35.63% (248/696) in Abaetetuba and 23.71% (165/696) in Breves. The male gender was predominant in 51.61% (128/248) of Abaetetuba cases and in 56.36% (93/165) of Breves cases; in Belém, women were the most affected, representing 50.53% (143/283) of the cases. The age group from 30 to 59 years was the most affected by ACD, 35.89% (89/248) in Abaetetuba and 53.71% (152/283) in Belém; which is different from Breves, where 32.73% (54/165) were between 0 and 14 years of age. The majority of those investigated reported was brown, 78.23% (194/248) from Abaetetuba, 68.90% (195/283) from Belém and 89.70% (148/165) from Breves. Low education prevailed among the cases: 42.74% (106/248) and 63.64% (105/165) of the investigated individuals had incomplete elementary school in Abaetetuba and Breves, respectively, and 17.69% (50/283) attended high school in Belém. It is highlighted the high percentage of under-registration of education of 34.63% (98/283) in Belém. In the urban area, there were 56.45% (140/248) and 96.11% (272/283) of the cases in Abaetetuba and Belém, respectively; Breves, 66.06% (109/165) of the cases in the rural area (Table 1).

Table 1 - Sociodemographic profile of ACD cases in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, Pará State, Brazil, from 2007 to 2015

| Variables | Abaetetuba | Belém | Breves | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 248 | % | N = 283 | % | N = 165 | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 128 | 51,61 | 140 | 49,47 | 93 | 56,36 |

| Female | 120 | 48,39 | 143 | 50,53 | 72 | 43,64 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 0-14 | 64 | 25,80 | 26 | 9,19 | 54 | 32,73 |

| 15-29 | 65 | 26,21 | 66 | 23,32 | 46 | 27,88 |

| 30-59 | 89 | 35,89 | 152 | 53,71 | 48 | 29,09 |

| ≥ 60 | 30 | 12,10 | 39 | 13,78 | 17 | 10,30 |

| Skin color | ||||||

| White | 41 | 16,53 | 24 | 8,48 | 9 | 5,45 |

| Black | 6 | 2,42 | 2 | 0,71 | 3 | 1,82 |

| Yellow | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0,61 |

| Brown | 194 | 78,23 | 195 | 68,90 | 148 | 89,70 |

| Indigenous | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1,21 |

| Disregarded | 4 | 1,61 | 53 | 18,73 | 2 | 1,21 |

| No information | 3 | 1,21 | 9 | 3,18 | - | - |

| Level of education | ||||||

| No education | 8 | 3,23 | 2 | 0,71 | 22 | 13,33 |

| Incomplete Elementary/Middle School | 106 | 42,74 | 47 | 16,61 | 105 | 63,64 |

| Completed Elementary/Middle School | 24 | 9,68 | 46 | 16,25 | 6 | 3,64 |

| High School | 50 | 20,16 | 50 | 17,67 | 9 | 5,45 |

| University/College | 4 | 1,61 | 17 | 6,01 | - | - |

| Disregarded | 9 | 3,63 | 98 | 34,63 | 3 | 1,82 |

| Not applicable | 29 | 11,69 | 8 | 2,82 | 16 | 9,70 |

| No information | 18 | 7,26 | 15 | 5,30 | 4 | 2,42 |

| Residence area | ||||||

| Urban | 140 | 56,45 | 272 | 96,11 | 53 | 32,12 |

| Periurban | 1 | 0,40 | 1 | 0,35 | 2 | 1,21 |

| Rural | 96 | 38,71 | 7 | 2,48 | 109 | 66,06 |

| Disregarded | - | - | 1 | 0,35 | - | - |

| No information | 11 | 4,44 | 2 | 0,71 | 1 | 0,61 |

Source: SINAN/MS; Secretary of State for Public Health (SESPA), 2017.

Disregarded: the investigated person did not know or could not give any information; No information: unregistered data; Not applicable: features not applicable to the investigated person; Conventional signal used: - Numerical data equal to zero, not resulting from rounding.

Laboratory diagnosis was carried out in 94.35% (234/248) of the cases in Abaetetuba, 97.88% (277/283) in Belém and 88.48% (146/165) in Breves (p < 0.0001). Most of the patients survived the infection and received hospital discharged for clinical follow-up after specific treatment. Of these, 97.17% (241/248) were from Abaetetuba, 92.94% (263/283) from Belém and 98.18% (162/165) from Breves (p < 0.0001). The cities reported deaths, 1.21% (3/248) in Abaetetuba, 2.12% (6/283) in Belém and 0.61% (1/165) in Breves. The lethality rate was 1.43% in the three cities. Oral infection occurred in 85.08% (211/248) of Abaetetuba cases, 71.38% (202/283) in Belém and 96.97% (160/165) in Breves (p < 0.0001). Specific treatment for asymptomatic patients was conducted in 98.39% (244/248), 96.11% (272/283) and 93.33% (154/165) of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves cases, respectively. Among the symptomatic cases, 60.08% (149/248) were from Abaetetuba, 6.36% (18/283) from Belém and 49.09% (81/165) from Breves, all patients received treatment. Regarding laboratory diagnosis, thick blood swear was performed in 66.13% (164/248) of the cases in Abaetetuba and 71.52% (118/165) in Breves. In the other hand, microhematocrit was widely used in Belém, in 45.58% (129/283) of the cases (Table 2).

Table 2 - Clinical and epidemiological profile of ACD cases in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, Pará State, Brazil, from 2007 to 2015

| Variables | Abaetetuba | Belém | Breves | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 248 | % | N = 283 | % | N = 165 | % | |

| Confirmation criteria | ||||||

| Clinical and epidemiological | 14 | 5,65 | 4 | 1,42 | 18 | 10,91 |

| Clinical | - | - | 1 | 0,35 | 1 | 0,61 |

| Laboratory | 234 | 94,35* | 277 | 97,88* | 146 | 88,48* |

| No information | - | - | 1 | 0,35 | - | - |

| Evolution of the case | ||||||

| Alive | 241 | 97,17* | 263 | 92,94* | 162 | 98,18* |

| Death from ACD | 3 | 1,21 | 6 | 2,12 | 1 | 0,61 |

| Death from another cause | - | - | 1 | 0,35 | - | - |

| Disregarded | 2 | 0,81 | 6 | 2,12 | - | - |

| No information | 2 | 0,81 | 7 | 2,47 | 2 | 1,21 |

| Possible mode of transmission | ||||||

| Transfusion | - | - | 4 | 1,42 | - | - |

| Vector | 27 | 10,89 | 3 | 1,06 | 4 | 2,42 |

| Vertical | 1 | 0,40 | - | - | - | - |

| Oral | 211 | 85,08* | 202 | 71,38* | 160 | 96,97* |

| Disregarded | 9 | 3,63 | 67 | 23,67 | 1 | 0,61 |

| No information | - | - | 7 | 2,47 | - | - |

| Specific treatment | ||||||

| Yes | 244 | 98,39 | 272 | 96,11 | 154 | 93,33 |

| No | 3 | 1,21 | 6 | 2,12 | 3 | 1,82 |

| No information | 1 | 0,40 | 5 | 1,77 | 8 | 4,85 |

| Symptomatic treatment | ||||||

| Yes | 149 | 60,08 | 18 | 6,36 | 81 | 49,09 |

| No | 91 | 36,69 | 77 | 27,21 | 67 | 40,60 |

| Disregarded | 0 | 0,00 | 12 | 4,24 | 1 | 0,61 |

| No information | 8 | 3,23 | 176 | 62,19 | 16 | 9,70 |

| Thick blood smear | ||||||

| Positive | 164 | 66,13 | 65 | 22,97 | 118 | 71,52 |

| Negative | 75 | 30,24 | 51 | 18,02 | 26 | 15,76 |

| Unrealized | 6 | 2,42 | 122 | 43,11 | 17 | 10,30 |

| No information | 3 | 1,21 | 45 | 15,90 | 4 | 2,42 |

| Strout/micro-hematocrit/QBC | ||||||

| Positive | 2 | 0,81 | 129 | 45,58 | 5 | 3,03 |

| Negative | 39 | 15,72 | 86 | 30,39 | 36 | 21,82 |

| Unrealized | 201 | 81,05 | 28 | 9,90 | 118 | 71,52 |

| No information | 6 | 2,42 | 40 | 14,13 | 6 | 3,63 |

Source: SINAN/MS; SESPA, 2017.

Disregarded: the investigated did not know or could not give any information; No information: unregistered data; Conventional sign used: - Numerical data equal to zero, not resulting from rounding; Chi-square test of adhesion; * p< 0.0001.

According to the symptoms of the patients, 94.35% (234/248) were from Abaetetuba, 89.40% (253/283) from Belém and 95.75% (158/165) from Breves. Fever persisted in 91.93% (228/248) of the patients from Abaetetuba, 93.64% (265/283) from Belém and 93.33% (154/165) from Breves. Asthenia appeared in over 75% of cases in the three municipalities. Face/limbs edema, meningoencephalitis and hepatomegaly were evidenced in 42.05% (119/283), 1.06% (3/283) and 7.77% (22/283) of the cases in Belém, respectively. Splenomegaly was observed in 4.84% (12/248) in Abaetetuba cases, 4.59% (13/283) in Belém and 13.33% (22/165) in Breves; and persistent tachycardia/arrhythmias were observed in 20.16% (50/248) of the cases in Abaetetuba, 13.78% (39/283) in Belém and 16.97% (28/165) in Breves. Polyadenopathy was observed in 1.61% (4/248) of Abaetetuba cases; and the presence of chagoma occurred in 2.42% (4/164) of the cases of Breve (Table 3).

Table 3 - Clinical profile of ACD cases in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, Pará State, Brazil, from 2007 to 2015

| Variables | Abaetetuba | Belém | Breves | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 248 | % | N = 283 | % | N = 165 | % | |

| Asymptomatic | ||||||

| Yes | 14 | 5,65 | 8 | 2,83 | 6 | 3,64 |

| No | 234 | 94,35 | 253 | 89,40 | 158 | 95,75 |

| Disregarded | - | - | 3 | 1,06 | - | - |

| No information | - | - | 19 | 6,71 | 1 | 0,61 |

| Face/limbs edema | ||||||

| Yes | 67 | 27,02 | 119 | 42,05 | 34 | 20,61 |

| No | 166 | 66,93 | 141 | 49,82 | 124 | 75,15 |

| Disregarded | - | - | 5 | 1,77 | - | - |

| No information | 15 | 6,05 | 18 | 6,36 | 7 | 4,24 |

| Meningoencephalitis | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | 0,81 | 3 | 1,06 | - | - |

| No | 228 | 91,93 | 222 | 78,45 | 157 | 95,15 |

| Disregarded | 3 | 1,21 | 30 | 10,60 | 1 | 0,61 |

| No information | 15 | 6,05 | 28 | 9,89 | 7 | 4,24 |

| Polyadenopathy | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 1,61 | 3 | 1,06 | 3 | 1,82 |

| No | 216 | 87,10 | 218 | 77,03 | 154 | 93,33 |

| Disregarded | 13 | 5,24 | 32 | 11,31 | 1 | 0,61 |

| No information | 15 | 6,05 | 30 | 10,60 | 7 | 4,24 |

| Persistent fever | ||||||

| Yes | 228 | 91,93 | 265 | 93,64 | 154 | 93,33 |

| No | 6 | 2,42 | 10 | 3,53 | 3 | 1,82 |

| Disregarded | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No information | 14 | 5,65 | 8 | 2,83 | 8 | 4,85 |

| Hepatomegaly | ||||||

| Yes | 24 | 9,68 | 22 | 7,77 | 23 | 13,94 |

| No | 200 | 80,65 | 220 | 77,74 | 135 | 81,82 |

| Disregarded | 8 | 3,22 | 13 | 4,59 | - | - |

| No information | 16 | 6,45 | 28 | 9,90 | 7 | 4,24 |

| ICC Signs | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 2,42 | 16 | 5,65 | 5 | 3,03 |

| No | 225 | 90,72 | 206 | 72,79 | 152 | 92,12 |

| Disregarded | 3 | 1,21 | 33 | 11,66 | 1 | 0,61 |

| No information | 14 | 5,65 | 28 | 9,90 | 7 | 4,24 |

| Persistent tachycardia/arrhythmias | ||||||

| Yes | 50 | 20,16 | 39 | 13,78 | 28 | 16,97 |

| No | 171 | 68,95 | 194 | 68,55 | 131 | 79,39 |

| Disregarded | 12 | 4,84 | 26 | 9,19 | - | - |

| No information | 15 | 6,05 | 24 | 8,48 | 6 | 3,64 |

| Asthenia | ||||||

| Yes | 187 | 75,40 | 223 | 78,80 | 127 | 76,97 |

| No | 45 | 18,14 | 44 | 15,55 | 30 | 18,18 |

| Disregarded | 2 | 0,81 | 1 | 0,35 | - | - |

| No information | 14 | 5,65 | 15 | 5,30 | 8 | 4,85 |

| Splenomegaly | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 4,84 | 13 | 4,59 | 22 | 13,33 |

| No | 211 | 85,08 | 229 | 80,92 | 136 | 82,43 |

| Disregarded | 9 | 3,63 | 12 | 4,24 | - | - |

| No information | 16 | 6,45 | 29 | 10,25 | 7 | 4,24 |

| Inoculation chagoma/Romaña’s sign | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | 0,81 | 2 | 0,70 | 4 | 2,42 |

| No | 228 | 91,93 | 244 | 86,22 | 152 | 92,12 |

| Disregarded | 3 | 1,21 | 8 | 2,83 | - | - |

| No information | 15 | 6,05 | 29 | 10,25 | 9 | 5,46 |

Source: SINAN/MS; SESPA, 2017.

Disregarded: the investigated did not know or could not give any information; No information: unregistered data. Conventional signal used: - Numerical data equal to zero, not resulting from rounding.

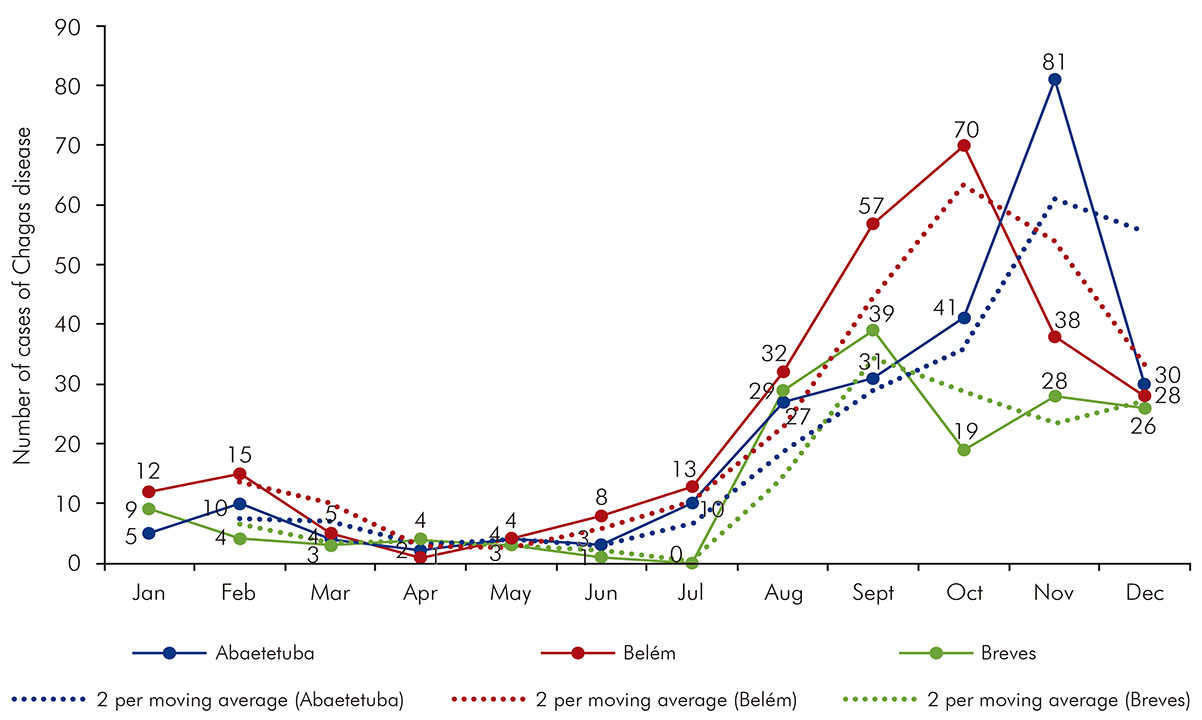

The monthly distribution of ACD cases had recorded an epidemic seasonality curve. A slight increase was observed in February, in Belém (15 cases) and Abaetetuba (10 cases), following a decreasing trend, and subsequent increase of great amplitude from July, in the three municipalities studied. For Abaetetuba, the ascending curve was continuous and recorded an epidemic peak in November (81 cases), decreasing in December (30 cases). For Belém, the ascending curve began in April (one case) and recorded an epidemic peak in October (70 cases), declining until December (28 cases). For Breves, notifications started from July (no case registration), but later with two epidemic peaks, the highest in September (39 cases) and the lowest in November (28 cases) (Figure 2).

Source: SINAN/MS; SESPA 2017.

Figure 2 - Monthly distribution of accumulated cases of ACD and moving average in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, Pará State, Brazil, from 2007 to 2015

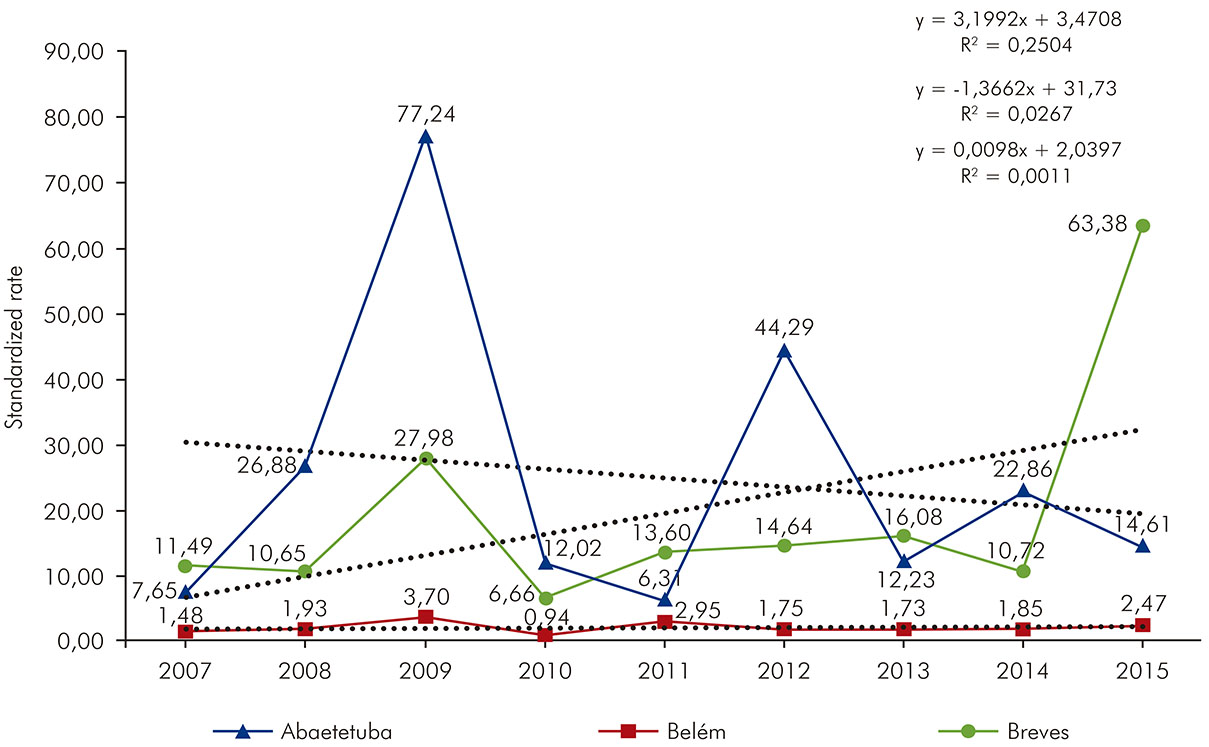

Abaetetuba showed three epidemic peaks in 2009 (77.24/100,000 inhabitants), 2012 (44.29/100,000 inhabitants) and 2014 (22.86/100,000 inhabitants), with a linear trend in decrease (R2 = 0.0267), which can be observed in figure 3 (dotted line). Belém presented the lowest incidence rate among the studied municipalities and presented a stable linear trend (R2= 0.0011). In Breves, two epidemic waves were evidenced, one in 2009 (27.98/100,000 inhabitants) and another in 2015 (63.38/100,000 inhabitants), recording a high linear trend increasing (R2= 0.2504) also shown in figure 3 (dotted line).

DISCUSSION

Vector control actions and intense surveillance in the screening of blood and organ donors carried out since 1975 and reduced the number of cases of ACD in Brazil14. However, since the 1990s, the Northern Region, an area previously considered non-endemic, has acquired public health importance due to the unusual epidemiological conditions of concurrent transmission (oral, indirect), which restarted the mandatory notification of acute cases in 200015. The mandatory notification has showed a public health problem neglected for decades in the Amazon. From 2007 to 2019, Pará recorded an average of 187.38 cases of ACD. Of the 154 outbreaks recorded in Brazil, from 2007 to 2016, 132 occurred in Pará, spread in 20 of its municipalities15. Barcarena, a municipality located in the northeast of the state, had the highest prevalence of the disease in Brazil, from 2007 to 201416. When reporting the occurrence of 283/696 cases of ACD in Belém, 248/696 in Abaetetuba and 165/696 in Breves, the present historical series reinforces this epidemiological context and the unquestionable magnitude of the disease in that region.

In the current study, ACD showed no preference for gender and age group. In Abaetetuba and Breves, men represented the majority of cases and, in Belém, women were the most affected by ACD. Adults (30-59 years of age) were the most infected by T. cruzi in Abaetetuba and Belém, and young people (0-14 years old) were the most infected patients in Breves. It is believed that exposure to the various routes of transmission is what probably determines the infection17. This is exemplified by the disagreement about the distribution of sex and age of the infected patients documented in the country6,7,16,17. The predominance of patients declared brown color results at the time of the 2010 Census, when 76.5% of people declared themselves as black and/or brown18, which justifies the prevalence of browns among those infected in the three municipalities studied and corroborates a study conducted in the municipality of Barcarena16. The sociodemographic profile of ACD cases in Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves is similar to that observed in the country. Of the 3,060 cases of ACD recorded from 2007 to 2019, men represented 53.56% of the cases, the mean age was 32 years (SD ± 20.15) and 77.81% declared themselves brown15.

The results of this study showed that both rural and urban areas have impacts against ACD. The cases were reported in large urban centers, such as Belém, the state capital (40.66%), and in smaller cities or even in rural areas, as observed in Abaetetuba (35.63%) (23.71%), respectively. The emergence and reemergence of ACD in urban and rural areas results from the combination of several factors such as: migratory currents, ecological imbalance, sociocultural and political and economic aspects19,20.

Deforestation in rural areas and the disordered growth of cities, due to rural-urban migration have caused the urbanization of the vector9,21. The higher proportion of cases of ACD registered in the urban region of Abaetetuba and Belém is justified by this significant migration of population. Simões et al.22 estimated that 500,000 people infected with T. cruzi have moved to major cities over the past three decades. In urban areas, the population lives in conditions of extreme poverty and precarious basic sanitation, which increases the risk of infection, the growth and permanence of neglected diseases23.

In Pará, recurrent deforestation for decades contributes to the reduction of wildlife habitat, which act as a natural reservoir of T. cruzi. The ecological imbalance brings man closer to the reservoirs, facilitating the transmission of the protozoan by the vector and food contamination (açaí) that is not processed according to good handling practices24. This chain of disease transmission was showed in the results of the present study. The oral route was the possible mode of infection of most patients (p < 0.0001). Breves had the lowest rate of development among the municipalities studied and the highest vegetation cover and also had the highest rate of oral infection (96.97%), followed by Abaetetuba (85.08%) and Belém (71.38%). However, the record of infection by donation of infected blood/organs only in Belém (1.42%) showed the need for the implementation and/or strengthening of integrated hemovigilance15.

The lack of access to goods and services due to social and economic precariousness was showed in data of this study. In the three municipalities studied, most of those infected by T. cruzi had low education (Elementary or High School). In Belém, 6.01% (17/283) of those patients affected had higher education; in Abaetetuba, these individuals represented 1.61% (4/248); and, in Breves, this data was not recorded, perhaps due to the difficulty in accessing higher education. These data show that individuals with higher educational level have greater possibility of access to information about the disease, which allowed changes in habits, reduced contamination therefore number of cases as reported by Sanmartino and Crocco25.

The lethality rate of the disease in Abaetetuba (1.21%) and Breves (0.61%) was similar to the annual lethality rate in Brazil (1.54%) and Pará (1.40%) from 2007 to 201915. In Belém, the lethality rate was higher (2.12%) when compared to the other evaluated cities, the state and the country. Belém acting as the largest center of hospital care for ACD cases in Pará and, sometimes, recording the number of cases that evolve to death from other municipalities. The implementation of assistance to people with ACD in the most remote and vulnerable municipalities in the Amazon is extremely important. That service would enable a preventive intervention, namely, the actions would occur before the emergence of complications of acute disease. The opportunity for early diagnosis is certainly another important issue, because it interferes in the prognosis of cases and, significantly, in the lethality of the disease4. The lack of investments for the diagnosis of ACD in the municipalities studied was showed when the smear (low cost) was the most used method for the ACD diagnosis in Abaetetuba (66.13%) and Breves (71.52%), and microhematocrit in Belém (45.58%). It is important to remember that there are no clinical criteria that allow accurately defining the cure of patients with ACD, which reinforces not only the importance of early diagnosis, but also the diagnosis (serological) for monitoring the disease26.

Clinical presentation was more frequently followed by febrile syndrome and asthenia. Previous studies have indicated that fever was the most predominant clinical manifestation in almost all cases27,28,29. Edema, although in smaller proportions in infected individuals from the municipalities of Abaetetuba (27.02%) and Breves (20.61%), was observed in 42.05% of the cases in Belém, similar to a study conducted in Manaus, which identified 31% of cases with lower limbs edema and 34.5% with facial edema29. The low percentages of inoculation chagoma/Romanã's sign recorded in the analyzed municipalities resulted from a decrease in vector infection rates. More than 93% of the cases reported in those three municipalities received specific treatment (asymptomatic individuals) provided by the SUS, with the aim of reducing cases through the cure of infection, the prevention of organic lesions or their evolution30; however, there is no evidence off clinical follow-up of cases after drug discharge, for at least five years in order to verify the evolution, considering the possibility of chronic disease.

The analysis of the temporal behavior of ACD is an important mechanism for understanding the epidemiological disease profile, which can be used as basis for improving health education measures and specific protection activities, aiming at reducing the occurrence of cases. The monthly distribution of ACD cases for those three municipalities recorded an epidemic seasonality curve, with a slight increase in the second month of the year in Abaetetuba and Belém; and an increase in the frequency of cases from July to October, a period in which the lowest rainfall rates are recorded, which favor greater mobility of triatomines which can facilitate contamination of the environment and food and fruits with infected feces. This period also coincides with the açaí harvest, which increases juice consumption and the risk of infection31.

The highest incidence rate of ACD was observed in Breves, because it presented trend growth ratio (R2= 0.2504) and for having presented two epidemic peaks, one in 2009 and another in 2015. In Abaetetuba, the incidence of the disease had a linear trend in decrease (R2= 0.0267), although three epidemic peaks were evidenced in 2009, 2012 and 2014. Belém drew attention by presenting a stable linear trend (R2= 0.0011) and the lowest incidence rate among the studied municipalities, despite the epidemic peak recorded in October, which occurred until December. The difference in the incidence of the disease in Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves is closely related to the degree of socioeconomic development and to the public policies for controlling and combating the disease in each locality. Historically, traditional peoples and communities (family farmers, rural workers, riverside populations, quilombola and indigenous communities) facing situations of inequality, violence and violation of rights are the most affected by that disease15.

CONCLUSION

The present study described the epidemiological profile of cases of ACD reported in the municipalities of Abaetetuba, Belém and Breves, there were individuals of both sexes, young and adult and residents of rural and urban areas. The vulnerability of the neglected population proved to be the predominant factor for increasing the risk of infection, followed by the destruction of the environment, which favors the transmission of T. cruzi by the vector and food contamination (açaí), and the absence of integrated healthcare surveillance. The epidemic curve of seasonality happened between August and November; and the municipality of Breves had the highest incidence rate of the disease, followed by Abaetetuba and Belém. Considering the variables studied, data obtained through the construction of the epidemiological scenario, which can assist healthcare managers with information focused on continuous and systematic surveillance, which guarantees universal access as a right.

REFERENCES

1 Dias JCP, Coura JR. Clínica e terapêutica da doença de Chagas: uma abordagem prática para o clínico geral. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz; 1997. Capítulo 3, Epidemiologia; p. 33-66. [ Links ]

2 Galvão C, organizador. Vetores da doença de Chagas no Brasil. Curitiba: Sociedade Brasileira de Zoologia; 2014. 289 p. Série Zoologia: guias e manuais de identificação. [ Links ]

3 Dias JCP, Borges Dias R. Aspectos sociais, econômicos e culturais da doença de Chagas. Cienc Cult. 1979;31:105-24. [ Links ]

4 Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças e Agravos não Transmissíveis e Promoção da Saúde. Saúde Brasil 2017: uma análise da situação de saúde e os desafios para o alcance dos objetivos de desenvolvimento sustentável [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2018 [citado 2019 jun 17]. 426 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/sinasc/saude_brasil_2017_analise_situacao_saude_desafios_objetivos_desenvolvimento_sustetantavel.pdf . [ Links ]

5 Lima MM, Alves RV, Costa JNG, Silva RA, Palmeira SL, Costa VM, et al. Doença de Chagas. Bol Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019 set [citado 2017 nov 16];50(n.esp.):16-8. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://ameci.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/boletim-especial-21ago19-web.pdf . [ Links ]

6 Coura JR. The main sceneries of Chagas disease transmission. The vectors, blood and oral transmissions - a comprehensive review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015 May;110(3):277-82. [ Links ]

7 Barbosa MGV, Ferreira JMBB, Arcanjo ARL, Santana RAG, Magalhães LKC, Magalhães LKC, et al. Chagas disease in the State of Amazonas: history, epidemiological evolution, risks of endemicity and future perspectives. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015 Jun;48(Suppl 1):27-33. [ Links ]

8 Beltrão HBM, Cerroni MP, Freitas DRC, Pinto AYN, Valente VC, Valente SA, et al. Investigation of two outbreaks of suspected oral transmission of acute Chagas disease in the Amazon region, Para State, Brazil, in 2007. Trop Doct. 2009 Oct;39(4):231-2. [ Links ]

9 Souza DSM, Monteiro MRCC. Manual de recomendações para diagnóstico, tratamento e seguimento ambulatorial de portadores de doença de Chagas. Belém: As Autoras; 2013. 50 p. [ Links ]

10 Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Coordenação-Geral de Desenvolvimento da Epidemiologia em Serviços. Guia de vigilância em saúde: volume único. 2. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2017. p. 441-61. [ Links ]

11 Secretaria de Estado da Saúde do Pará. Diretoria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Epidemiologia. Sistema de agravos de notificação. Belém: SESPA; 2018. [ Links ]

12 Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas. Anuário Estatístico do Pará 2018: População total e estimativas populacionais, Pará e municípios - 2013 a 2017 [Internet]. Belém: FAPESPA; 2018 [citado 2002 jul 23]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.fapespa.pa.gov.br/sistemas/anuario 2018/tabelas/demografia/tab_1.1_populacao_total_e_estimativas_populacionais_para_e_municipios_2013_a_2017.htm . [ Links ]

13 Ayres M, Ayres Jr M, Ayres DL, Santos AAS. BioEstat 5.0: aplicações estatísticas nas áreas das ciências biológicas e médicas. Belém: Sociedade Mamirauá; 2007. 364 p. [ Links ]

14 Dias JCP, Cláudio LDG, Lima MM, Albajar-Viñas P, Silva RA, Alves RV, et al. Mudanças no paradigma da conduta clínica e terapêutica da doença de Chagas: avanços e perspectivas na busca da integralidade da saúde. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2016 jun;25(n. esp.):87-90. [ Links ]

15 Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Doença de Chagas: 14 de abril - Dia Mundial. Bol Epidemiol. 2020 abr;51(n.esp.):1-43. [ Links ]

16 Sousa Jr AS, Palácios VRCM, Miranda CS, Costa RJF, Catete CP, Chagasteles EJ, et al. Análise espaço-temporal da doença de Chagas e seus fatores de risco ambientais e demográficos no município de Barcarena, Pará, Brasil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2017 out-dez;20(4):742-55. [ Links ]

17 Coura JR, Borges-Pereira J. Chagas disease: 100 years after its discovery. A systemic review. Acta Trop. 2010 Jul-Aug;115(1-2):5-13. [ Links ]

18 Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico de 2010 [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2010 [citado 2018 mai 26]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://ww2.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/resultados_gerais_amostra/resultados_gerais_amostra_tab_uf_xls.shtm . [ Links ]

19 Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwatkin D, Claeson M, Habicht JP. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet. 2003 Jul;362(9379):233-41. [ Links ]

20 Dias JCP. Human Chagas disease and migration in the context of globalization: some particular aspects. J Trop Med. 2013;2013:789758. [ Links ]

21 Monteiro WM, Magalhães LKC, Sá ARN, Gomes ML, Toledo MJO, Borges L, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi IV causing outbreaks of acute Chagas disease and infections by different haplotypes in the western Brazilian Amazonia. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41284. [ Links ]

22 Simões MV, Romano MMD, Schmidt A, Martins KSM, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiovasc Sci. 2018;31(2):173-89. [ Links ]

23 Matos R. Periferias de grandes cidades e movimentos populacionais. Cad Metropol. 2005;13:71-105. [ Links ]

24 Rassi A, Rassi Jr A. Doença de Chagas aguda. In: Lopes AC, Guimarães HP, Lopes RD, Vendrame LS. Programa de atualização em medicina de urgência e emergência. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2013. p. 41-85. [ Links ]

25 Sanmartino M, Crocco L. Conocimientos sobre la enfermedad de Chagas y factores de riesgo en comunidades epidemiológicamente diferentes de Argentina. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2000;7(3):173-8. [ Links ]

26 Ministério da Saúde (BR). Municípios de residência de casos agudos confirmados no SINAN no período de 2007 a 2016* [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde ; 2017 [citado 2017 dez 10]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2017/novembro/13/LISTA-DE-MUNICIPIOS-DE-RESID--NCIA-DE-CASOS-AGUDOS-CONFIMARDOS-NO-SINAN.pdf . [ Links ]

27 Pinto AYN, Valente SA, Valente VC, Ferreira Jr AG, Coura JR. Acute phase of Chagas disease in the Brazilian Amazon region: study of 233 cases from Pará, Amapá and Maranhão observed between 1988 and 2005. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008 Nov-Dec;41(6):602-14. [ Links ]

28 Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Carvalho NB. Oral transmission of Chagas disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(6):845-52. [ Links ]

29 Monteiro WM, Barbosa MGV, Toledo MJO, Fé FA, Fé NF. Série de casos agudos de doença de Chagas atendidos num serviço terciário de Manaus, Estado do Amazonas, de 1980 a 2006. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010 mar-abr;43(2):207-10. [ Links ]

30 Araújo-Jorge TC, Castro SL, organizadoras. Doença de Chagas: manual para experimentação animal. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2000. 368 p. [ Links ]

31 Steindel M, Dias JCP, Romanha AJ. Doença de Chagas, mal que ainda preocupa. Cienc Hoje. 2005;37(217):32-8. [ Links ]

6Article originally published in Portuguese (http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/S2176-6223202000245)

How to cite this article / Como citar este artigo: Vilhena AO, Pereira WMM, Oliveira SS, Fonseca PFL, Ferreira MS, Oliveira TNC, et al. Acute Chagas disease in Pará State, Brazil: historical series of clinical and epidemiological aspects in three municipalities, from 2007 to 2015. Rev Pan Amaz Saude. 2020;11:e202000245. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/S2176-6223202000245

Received: April 05, 2019; Accepted: June 03, 2020

texto em

texto em