Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Pan-Amazônica de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 2176-6215versão On-line ISSN 2176-6223

Rev Pan-Amaz Saude vol.12 Ananindeua 2021 Epub 27-Dez-2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s2176-6223202100963

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Clinical and sociodemographic profile of patients affected by stingrays stings and treatments applied

1 Instituto Tocantinense Presidente Antônio Carlos, Curso de Graduação em Medicina, Palmas, Tocantins, Brasil

OBJECTIVES:

To characterize the clinical and sociodemographic profile of patients and treatments applied to trauma caused by stingrays in Palmas, Tocantins State, Brazil, from 2018 to 2019.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Descriptive and quantitative study with data from 189 electronic medical records of patients seen by medical professionals in the Emergency Care Units of Palmas. Sociodemographic and clinical variables were investigated. Data analysis was performed using the Stata 11 software, and the results were presented in tables and graphs.

RESULTS:

There was a predominance of males (75.66%), age group between 21 and 50 years (69.31%), and brown skin color (48.15%). The accidents occurred predominantly from June to September (46.56%) and in residents of the Plano Diretor Sul neighborhood (22.75%). The search for medical assistance within 24 h occured in 61.91% of cases. Local signs and symptoms (91.53%) and yellow risk classification (61.38%) by the Manchester Protocol also stood out. Complications were reported for 17.46% of patients, and 7.41% were referred. The most used therapies were local and systemic analgesics, including opioids (61.90%), anti-inflammatory drugs (61.38%), and antibiotics (59.26%).

CONCLUSION:

The accidents caused by stingrays occurred mostly during the dry season. The predominance of accidents among residents of the Plano Diretor Sul coincides with the greater availability of beaches and baths in this region. These data report the need for health education for bathers, fishers, and exposed populations and the need for specific protocols and trained professionals to manage this condition in health services.

Keywords: Animals, Poisonous; Epidemiology; Therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

Brazil has the most extensive river network globally, whith many venomous animals1. Among these animals are the freshwater stingrays of the Potamotrygonidae family, distributed in four genera: Potamotrygon, Paratrygon, Plesiotrygon, and Heliotrygon2. Confined to continental waters, stingrays have a wide distribution in South America, and about 20 species colonize all regions of Brazil3,4,5. The Paratrygon aiereba species is the most common in the Tocantins-Araguaia basin, with the largest geographic distributions among the species of the genus6.

The Tocantins-Araguaia basin is frequently used for recreational activities, especially between June and August. Due to the dry season, there is a decrease in river water levels and consequent exposure of beaches, which attract tourists, where accidents with stingrays are common6,7. These animals usually remain motionless, hidden by sand or mud at the bottom of rivers, with their eyes located dorsally, watching for the possibility of food and hiding from their predators8. Thus, bathers have accidents after stepping on stingrays, as they are hit, predominantly, in the lower limbs such as ankles and feet, while fishers, both professional and sports, are usually hit in the upper limbs, especially the hands when trying to manipulate them9.

Stingrays of the Potamotrygonidae family are known for their long-tailed appendage, with one to four serrated calcified stingers covered by a glandular epithelium whose cells produce venom10. In addition, stingrays, like other fish, are covered in mucus that harbors various bacteria types that can cause secondary bacterial infections6,11. This mucus contains substances, such as peptides, which induce inflammation and vasoconstriction and, combined with the venom, increase the severity of injuries caused by the animal5,10. In this way, when threatened, stingrays use their tail as a whip5,8,10, causing a severe injury by mechanical action, which can traumatize the main nerves and blood vessels, and by chemical, through the release of toxins in the wound6,8,10,11.

Pain is the main reported symptom, appearing with great intensity immediately after the sting, followed by local edema and erythema, evolving to cutaneous necrosis of variable degree5,9. The wound is often disproportionately painful in relation to the visible clinical lesion8, being persistent even with the use of anesthetics, analgesics, and anti-inflammatories6. Systemic symptoms such as tachycardia, fever, cold sweating, nausea, vomiting, and agitation have also been described and are usually associated with the victim's pain and stress7,8. The average patient recovery time and ulcer healing take about three months; however, severe poisonings that are not adequately treated can result in amputation or death6,7.

Sting damage is aggravated because there is still no specific treatment for this category of accident. In addition, many health professionals do not receive adequate training while graduating or during their professional activity9. Some literature reports have shown antibothropic serum being administered for pain and inflammation and the use of ice compress; however, these procedures are not indicated because of their low effectiveness6, and the use of hot compresses in these cases is ideal5,6,9. This reflects the poor preparation of health professionals in managing these patients.

Given the need for scientific evidence on the treatment approaches used, this study aimed to identify the therapies applied to stingray sting trauma from 2018 to 2019 and characterize patients' clinical and sociodemographic profiles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was carried out in Palmas, Tocantins State, which has a territorial area of 2,218,942 km² and had a population of 306,296 inhabitants in 201912. This territory is part of a transition area from the Cerrado to the Amazon, with a tropical climate, with an average annual temperature of 26.7 °C. Palmas is bathed by a lake formed from the Luís Eduardo Magalhães hydroelectric plant, 172 km long and 8 km wide, with islands and artificial beaches throughout the year (Figure 1). As it is a city with a tropical and hot climate, between June and October, bathers are more frequent for leisure activities, providing opportunities for trauma by stingrays. For the health care of this category of accident, the municipality has the Palmas General Hospital, under State management, and two Emergency Care Units (Unidade de Pronto Atendimento - UPA), under Municipal management. For this study, the investigation was conducted in the two UPAs, one located in the Plano Diretor Norte and the other in the Plano Diretor Sul (Figure 1).

Source: Adapted from Google Maps.

Figure 1 - Location of the two UPAs and main beaches in Palmas, Tocantins, Brazil

This is a descriptive and quantitative study. For data collection, the municipal management provided the database with all electronic medical records (e-SUS) of victims of stingray sting trauma treated at the UPAs between 2018 and 2019. The data collection was conducted from October to November 2020. The selection of medical records was made by applying the keywords "stingrays", "stingray", "rays", and "ray". From this procedure, 774 medical records were obtained.

After analysis, only medical records containing complete information on the first care provided by the medical professional were included. Records with duplicate information, diagnostic errors and discrepancies regarding the category of accident/trauma, and records without therapeutic and clinical information were excluded. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 189 patients participated in the study.

Data were collected using the following sociodemographic variables: gender, age group, race/skin color, month of the accident, place of origin; and clinical variables: anatomical region of the lesion, seeking time for medical care, signs and symptoms, complications, referrals made, risk classification by the Manchester Protocol, and category of treatment applied.

For the descriptive analysis of the data, the software Stata 11 (Stata Corp., College Station, United States of America) was used, and the data were organized and presented in tables and graphs.

The study was approved by the Project and Research Evaluation Committee of the Fundação Escola de Saúde Pública de Palmas. It was then submitted to and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Presidente Antônio Carlos University Center, Araguaína, Tocantins (CAEE: 33623720.4.0000.0014, of July 14, 2020), and obtained the registration of the co-participating institution from which the data were collected.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic profile (Table 1) showed that most victims were male, representing 143/189 cases (75.66%) of the total. As for the age group, patients between 21 and 50 years old stood out (69.31%). There was a predominance of brown race/skin color (48.15%) and accidents between June and September (46.56%). The most affected population was from the Plano Diretor Sul of Palmas (22.75%).

Table 1 - Sociodemographic characterization of victims of stingray sting trauma treated at UPAs in the north and south of Palmas, Tocantins State, Brazil, from 2018 to 2019

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 46 | 24.34 |

| Male | 143 | 75.66 |

| Age group | ||

| ≤ 20 years | 35 | 18.52 |

| 21 to 50 years | 131 | 69.31 |

| > 50 years | 23 | 12.17 |

| Race/skin color | ||

| Brown | 91 | 48.15 |

| White | 53 | 28.04 |

| Yellow | 34 | 17.99 |

| Black | 11 | 5.82 |

| Month of the accident | ||

| January to May | 66 | 34.92 |

| June to September | 88 | 46.56 |

| October to December | 35 | 18.52 |

| Place of origin | ||

| Plano Diretor Sul | 43 | 22.75 |

| Another state | 33 | 17.46 |

| Another city | 27 | 14.29 |

| Aureny I, II, III and IV | 29 | 15.34 |

| Plano Diretor Norte | 22 | 11.64 |

| Taquaralto | 19 | 10.05 |

| Taquari | 9 | 4.76 |

| Taquaruçu | 2 | 1.06 |

| Others* | 5 | 2.65 |

| Total | 189 | 100.00 |

* Água Fria, Sonho Meu, and Irmã Dulce subdivisions and rural areas.

The clinical profile observation (Table 2) showed that the seeking time for medical care within 24 hours (61.91%) was the most prevalent. Local signs and symptoms (91.53%) were dominant. Regarding the screening of care according to the risk classification by the Manchester Protocol, it was found that 61.38% received a yellow classification (urgent). Only 17.46% of the patients had some complication, and 7.41% generated referrals.

Table 2 - Clinical characterization of victims of stingray sting trauma treated at the UPAs in the north and south of Palmas, Tocantins State, Brazil, from 2018 to 2019

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical region of the lesion | ||

| Lower limbs | 170 | 89.95 |

| Upper limbs | 9 | 4.76 |

| Upper and lower limbs | 1 | 0.53 |

| Mentum | 1 | 0.53 |

| Trunk | 1 | 0.53 |

| Not defined | 7 | 3.70 |

| Seeking time for medical care | ||

| Up to 24 hours | 117 | 61.91 |

| 1 to 7 days | 13 | 6.88 |

| Over 7 days | 19 | 10.05 |

| Not specified | 40 | 21.16 |

| Risk classification* | ||

| Green | 19 | 10.05 |

| Yellow | 116 | 61.38 |

| Red | 19 | 10.05 |

| Not informed | 35 | 18.52 |

| Signs and symptoms | ||

| Local | 173 | 91.53 |

| Systemic | 16 | 8.47 |

| Complications | ||

| Yes | 33 | 17.46 |

| No | 14 | 7.41 |

| Ignored | 142 | 75.13 |

| Referrals made | ||

| Yes | 14 | 7.41 |

| No | 175 | 92.59 |

| Total | 189 | 100.00 |

* Green: Little urgent, medical care within 2 hours; Yellow: Urgent, medical care within 1 h; Red: Severe, immediate medical care.

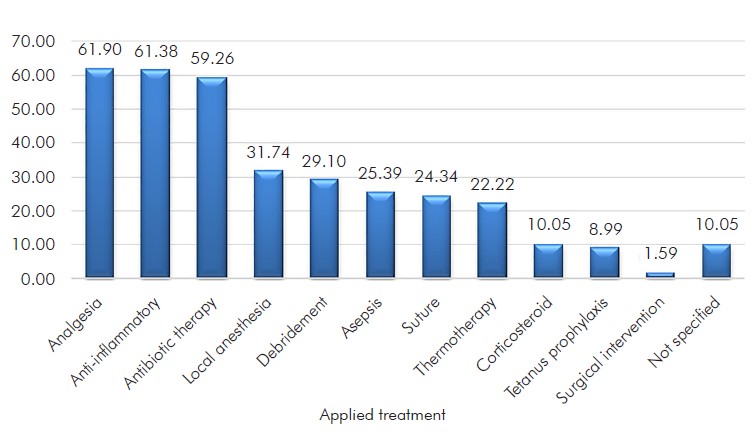

The therapeutic profile (Figure 2) was traced according to the total number of times a certain drug class was prescribed. The most used therapies consisted in local and systemic analgesics, including opioids (61.90%), anti-inflammatory drugs (61.38%), and antibiotics (59.26%). The records classified as "not specified" refer to developments not recorded in the medical records.

Figure 2 - Therapeutic characterization of victims of stingray sting trauma treated at the UPAs in the north and south of Palmas, Tocantins State, Brazil, from 2018 to 2019

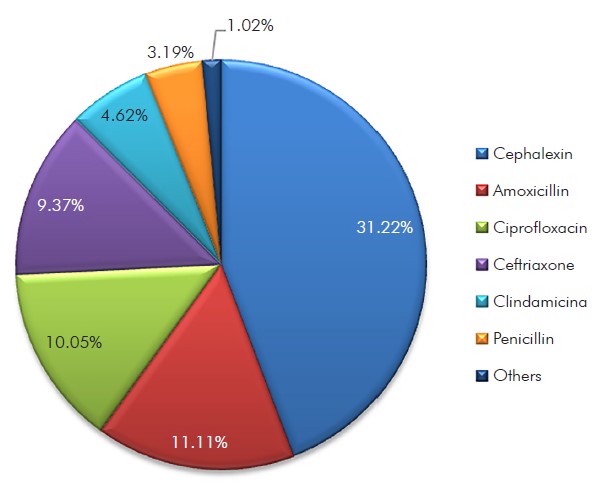

The most prescribed antibiotics (Figure 3) were cephalexin (31.22%), amoxicillin (11.11%), and ciprofloxacin (10.05%). There was overlapping prescription of anti-inflammatory drugs for the same patient, and the most prescribed were tenoxicam (125; 66.14%), ibuprofen (61; 32.27%), nimesulide (60; 31.75%), diclofenac (22; 11.64%), corticosteroids (19; 10.05%), meloxicam (3; 1.59%), aceclofenac (1; 0.53%), ketoprofen (1; 0.53%), naproxen (1; 0.53%), and piroxicam (1; 0.53%).

DISCUSSION

This study provided a comprehensive understanding of the therapies adopted in the UPAs of Palmas for cases of accidents caused by stingrays, in addition to favoring the delineation of the sociodemographic and clinical profiles of patients who suffered this type of trauma. The results showed greater incidence in the age group between 21 and 50 years, in residents from the Plano Diretor Sul, males, brown race/skin color, and from June to September. The most common clinical profile was lesions in the lower limbs, with local signs and symptoms, and urgent risk classification (yellow) by the Manchester Protocol in patients who sought medical care within 24 h, with rare referrals and complications in the medical records. Regarding therapies, there was a predominance of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and antibiotics.

The Tocantins State is mainly composed of brown race/skin color, which corresponds to more than 60% of the population12. This data corroborates the possibility of the predominance of accidents with stingrays in the brown race/skin color.

In the Tocantins-Araguaia basin, mainly in Tocantins, Mato Grosso, and Pará, accidents with stingrays are more frequent during the dry season, between July and August, when sandbanks and beaches appear, and thousands of people seek them to perform recreational activities6,7. Thus, the highest accident records found from June to September were expected. Amateur fishers are also frequently injured in April and May when there is the fishing season of native species, and the inhabitants of the Southeast Region look for the Amazon and Tocantins-Araguaia rivers to practice sport fishing. In this context, stings occur due to the manipulation of stingrays trapped in hooks and trampling11. This scenario explains the high number of patients treated between January and May and the care provided to residents from other states.

In Palmas, most affected patients come from the Plano Diretor Sul. This is likely due to its proximity to the city's lake, which has beaches throughout the year. Haddad Jr et al.7 observed that, in the Tocantins River, due to the flooding of extensive areas caused by the construction of hydroelectric plants, artificial islands and beaches were built and are used every month by local inhabitants for leisure, which contributes to this type of accident occurring throughout the year. Another factor contributing to the increase in these animals interactions with humans is the damming, which reduces the water flow, making stingrays food available, leading to their increase, as has already been observed in Lake Tucuruí, in Marabá and Tucuruí, Pará State, and in the Lajeado hydroelectric plant, in Palmas7.

Males have already been found as the most affected in other studies on accidents with stingrays in Tocantins13. This factor may be associated with men's high-risk behavior pattern14 and the practice of fishing, which is significantly associated with this type of injury5,7,9,15. In a study carried out in the Amazon, which analyzed 476 cases of stingray stings, the age group between 21 and 50 years was also the most recorded, accounting for 44.1% of the injuries12.

Stingray accidents are characterized by inflammatory action, in which the victim complains of intense pain that is disproportionate to the size of the lesion and the appearance of erythema and edema around the wound, which constitutes the first stage of envenomation5,16. In a study carried out in 2015 with rats, it was concluded that the venom of the Potamotrygon motor induces edema formation in just 15 min after injection into the rats' paws. In addition, a large number of inflammatory cells were observed soon after the venom injection and in later periods17. The lesion evolves with central necrosis, tissue sagging, and a pink ulcer formation5,10. The analysis of histopathological changes induced by the Potamotrygon falkneri venom made it possible to verify that, 6 h after the injection, there is the appearance of inflammatory infiltrates and foci of necrosis in basal epidermal cells. In 24 h, necrosis of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and skeletal muscle can be observed, which may cause serious complications, such as rhabdomyolysis, due to coagulative necrosis of muscle tissue5,11.

Stingray sting damage is more common in the lower limbs, especially the foot and ankle5,7,9,15,16,18. This is mainly due to stingrays' benthic habit, which are usually hidden under the sand, making it easier to be stepped on, and use the stinging as a defense mechanism5. However, there were also records of cases of stinging in the mentum and trunk in this study.

In the visits evaluated in the UPA, the signs and symptoms were mostly local, and intense pain in the sting region was the most reported complaint, followed by local edema, hyperemia, and erythema. Intense pain in the affected region was the symptom predominantly responsible for the yellow risk classification by the Manchester Protocol, referred to as urgent, and it was the most found in the triage. Studies show that in some cases, the pain is so intense that it can cause disorientation and behavioral changes7,16. The red classification, emergency, was indicated for these patients, especially those who had a hypertensive peak at the time of care.

The early seeking time after the sting is essential, as severe envenomations with delayed medical care or clinical mismanagement can result in major complications6. A study carried out in Amazonas State showed that a time greater than 24 h to seek medical assistance was significantly associated with the risk of secondary infection, and the delay in medical care can increase the risk of secondary infection up to 15 times in the Brazilian Amazon16. This study observed that of the 19 patients who sought the service only seven days after the accident, 17 had complications. Such complications manifested essentially in phlogistic signs and secondary infections. Besides, a necrosis case was reported, which led to a referral to the Palmas General Hospital for surgical intervention16.

Proper treatment for stingray envenomation remains poorly understood and somewhat controversial in the Brazilian medical community6. Of the recommended therapies, the use of thermotherapy through immersion of the limb in hot water, hot compress, and/or washing with warm saline was used and oriented to patients by doctors in only 22.22% of the consultations analyzed in this study. Immersion of the limb in hot, non-scalding water, between 45 °C and 60 °C, is the first and most indicated procedure for pain control, as the venom toxins present in the barb are thermolabile, and this measure also reduces the vasoconstriction effect5,7,9. A prospective study conducted in California reported a rapid reduction in pain scale in patients after a relatively short period of immersion of the affected limbs19.

However, it is known that after the removal of the affected limb from hot water, the pain may persist. The use of oral analgesia, titrated intravenous opioids, and local anesthesia (or locoregional block) is recommended, which should be administered in cases where thermotherapy is not sufficient to relieve acute pain16. According to the manual for diagnosis and treatment of accidents by venomous animals of the National Health Foundation20, local blockade with 2% lidocaine without vasoconstrictor is indicated, aiming not only to reduce pain but also to facilitate the manipulation of the injured tissue to remove possible foreign bodies. In this study, local anesthesia was administered in 31.74% of patients.

Asepsis (25.39%) was recommended for this category of injury. All penetrating injuries require irrigation and cleaning. Larger wounds or wounds containing debris require surgical exploration to extract any remaining embedded tail fragments, as well as wound debridement19. Debridement was performed in 29.10% of cases and surgical intervention in only 1.59% of patients. Some authors recommend early excision of the affected area however, its application is not always possible due to the imprecise delineation of the necrotic area in the early stages of the condition6.

Another little-exercised procedure was tetanus prophylaxis, observed in only 8.99% of the cases. Tetanus can occur after trauma, as its development is not uncommon in people with necrotic tissue, and necrosis is an essential precondition for the multiplication of Clostridium tetani12. Thus, tetanus prophylaxis is recommended in post-injury treatment5,7,8,16,17.

Antibiotic prophylaxis after stingray stinging also remains controversial, as some studies recommend its use only for wounds with deep sting penetration, significant foreign bodies in the wound, or for immunocompromised victims. However, a study on patients' care in the emergency showed that 17% of those who did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis had infection and returned for further treatment, and only 1.4% of those who received antibiotic prophylaxis returned19.

The most common microbial agents in the P. motor stingray mucus are gram-negative rods, namely Aeromonas spp., including β-lactam-resistant bacterial strains with the potential to cause severe secondary infection16. Pseudomonas spp. and Staphylococcus spp. are also agents associated with secondary infections5. The use of quinolone for at least five days showed a lower rate of infection8,15. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin or tetracycline have also been suggested to treat wound infections caused by accidents with fish16.

However, even though bacterial species are generally susceptible to ciprofloxacin, which is one of the most prescribed antibiotic drugs for patients in this study (10.05%), there are reports of therapeutic failure of this drug6,16, mainly due to bacterial resistance of species that colonize stingray mucus, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter spp., and Clostridium perfringens6.

Cephalexin, a first-generation cephalosporin, was the most used antibiotic medication (31.22%). Although these drugs have been successful in the treatment, they are antibiotics known for their resistance to several bacterial species relevant to poisonings caused by Potamotrygon, like Citrobacter freundii, P. aeruginosa, Aeromonas hydrophila, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp., and K. pneumoniae6.

In traumas caused by stingrays, anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended to control the progression and worsening of the wound5,6. Still, its use and applicability are not widely discussed in the literature. The use of systemic corticosteroids is controversial and may prolong the healing time of ulcers7,9.

CONCLUSION

In short, accidents caused by stingrays treated in the emergency services of Palmas occurred predominantly in the dry season, with young men, and brown race/skin color being the most affected. The predominance of accidents among residents of the Plano Diretor Sul coincides with the greater availability of beaches and bathing in this region. In the therapeutic management, there was a predominance of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and antibiotics.

According to the literature, the primary measure recommended is the immersion of the affected area in hot water. However, this study showed that this conduct was not recommended in the consultations. The antibiotics most used in managing cases presented bacterial resistance and may not be as effective in the prophylactic treatment of wounds. Other treatments, such as corticosteroids, may also be debatable. Therefore, health professionals in the emergency services are unprepared and possibly unfamiliar with the management of this category of injury. These data report the need for health education for bathers, fishers, and exposed populations, specific protocols, and trained professionals to manage this condition in health services.

REFERENCES

1 Haddad Jr V. Animais aquáticos de importância médica no Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003 set-out;36(5):591-7. Doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822003000500009 [Link] [ Links ]

2 Rosa RS, Charvet-Almeida P, Quijada CCD. Biology of the South American potamotrygonid stingrays. In: Carrier JC, Musick JA, Heithaus MR (editors). Sharks and their relatives II: biodiversity, adaptive physiology, and conservation. Washington: CRC Press; 2010. Chapter 5; p. 241-86. [ Links ]

3 Fontenelle JP, Marques FPL, Kolmann MA, Lovejoy NR. Biogeography of the neotropical freshwater stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygoninae) reveals effects of continent-scale paleogeographic change and drainage evolution. J Biogeogr. 2021 Mar;48(6):1406-19. Doi: 10.1111/jbi.14086 [Link] [ Links ]

4 Almeida MP, Barthem RB, Viana AS, Almeida PC. Diversidade de raias de água doce (Chondrichthyes: Potamotrygonidae) no estuário amazônico. Arq Cien Mar. 2008;41(2):82-9. Doi: 10.32360/acmar.v41i2.6067 [Link] [ Links ]

5 Lameiras JLV, Costa OTF, Santos MC, Duncan WLP. Arraias de água doce (Chondrichthyes - Potamotrygonidae): biologia, veneno e acidentes. Sci Amazon. 2013;2(3):11-27. [Link] [ Links ]

6 Rincon Filho G. Aspectos taxonômicos, alimentação e reprodução da raia de água doce Potamotrygon orbignyi (Castelnau) (Elasmobranchii: Potamotrygonidae) no rio Paraná-Tocantins [Tese]. Rio Claro (SP): Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências; 2006. [Link] [ Links ]

7 Haddad Jr V, Cardoso JLC, Garrone Neto D. Injuries by marine and freshwater stingrays: history, clinical aspects of the envenomations and current status of a neglected problem in Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2013 Jul;19(1):16. Doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-19-16 [Link] [ Links ]

8 Hoyos Franco MA, Posso Zapata C, Cardenas YA. Necrosis cutánea severa por picadura de raya en el miembro inferior: presentación de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Cir Plast Iberolatinoam. 2009 oct-dic;35(4):327-32. [Link] [ Links ]

9 Garrone Neto D, Haddad Jr V. Arraias em rios da região Sudeste do Brasil: locais de ocorrência e impactos sobre a população. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010 jan-fev;43(1):82-8. Doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822010000100018 [Link] [ Links ]

10 Oliveira Jr NG, Fernandes GR, Cardoso MH, Costa FF, Cândido ES, Garrone NetoD, et al. Venom gland transcriptome analyses of two freshwater stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygonidae) from Brazil. Sci Rep. 2016 Feb;6:21935. Doi: 10.1038/srep21935 [Link] [ Links ]

11 Antoniazzi MM, Benvenuti LA, Lira MS, Jared SGS, Garrone Neto D, Jared C, et al. Histopathological changes induced by extracts from the tissue covering the stingers of Potamotrygon falkneri freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2011 Feb;57(2):297-303. Doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.12.005 [Link] [ Links ]

12 Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Cidades e Estados. Tocantins [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2020 [citado 2020 mai 10]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://ibge.gov.br/estadosat/perfil.php?sigla=to . [ Links ]

13 Turíbio TO. Caracterização biológica do muco epidérmico da arraia de água doce Paratrygon aiereba [Tese]. São Paulo (SP): Universidade de São Paulo; 2018. Doi: 10.11606/T.85.2020.tde-04022020-161042 [Link] [ Links ]

14 Moura E. Perfil da situação de saúde do homem no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto Fernandes Figueira; 2012. [Link] [ Links ]

15 Hønge BL, Patsche CB, Jensen MM, Schaltz-Buchholzer F, Baad-Hansen T, Wejse C. Case report: iatrogenic infection from traditional treatment of stingray envenomation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018 Mar;98(3):929-32. Doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0863 [Link] [ Links ]

16 Sachett JAG, Sampaio VS, Silva IM, Shibuya A, Vale FF, Costa FP, et al. Delayed healthcare and secondary infections following freshwater stingray injuries: risk factors for a poorly understood health issue in the Amazon. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018 Sep-Oct;51(5):651-9. Doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0356-2017 [Link] [ Links ]

17 Kimura LF, Prezotto-Neto JP, Távora BCLF, Faquim-Mauro EL, Pereira NA, Antoniazzi MM, et al. Mast cells and histamine play an important role in edema and leukocyte recruitment induced by Potamotrygon motoro stingray venom in mice. Toxicon. 2015 Sep;103:65-73. Doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.06.006 [Link] [ Links ]

18 Abati PAM, Torrez PPQ, França FOS, Tozzi FL, Guerreiro FMB, Santos SAT, et al. Injuries caused by freshwater stingrays in the Tapajós River Basin: a clinical and sociodemographic study. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017 May-Jun;50(3):374-8. Doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0016-2017 [Link] [ Links ]

19 Myatt T, Nguyen BJ, Clark RF, Coffey CH, O’Connell CW. A prospective study of stingray injury and envenomation outcomes. J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;55(2):213-7. Doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.04.035 [Link] [ Links ]

20 Ministério da Saúde (BR). Fundação Nacional de Sáude. Manual de diagnóstico e tratamento de acidentes por animais peçonhentos. 2. ed. rev. Brasília: Fundação Nacional de Sáude; 2001. [Link] [ Links ]

How to cite this article / Como citar este artigo: Silva DP, Calumby RJN, Silva LNR, Oliveira JO, Sousa JRG, Silva DC, et al. Clinical and sociodemographic profile of patients affected by stingrays stings and treatments applied. Rev Pan Amaz Saude. 2021;12:e202100963. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/S2176-6223202100963

Received: April 29, 2021; Accepted: November 01, 2021

texto em

texto em