Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Pan-Amazônica de Saúde

versão impressa ISSN 2176-6215versão On-line ISSN 2176-6223

Rev Pan-Amaz Saude vol.13 Ananindeua 2022 Epub 21-Jan-2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5123/s2176-6223202200894

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Bacteriological analysis of cell phones in a public health service in Belém, Pará State, Brazil

1 Centro Universitário Metropolitano da Amazônia, Belém, Pará, Brasil

2 Universidade Federal do Pará, Laboratório de Neuropatologia Experimental, Belém, Pará, Brasil

OBJECTIVES:

To carry out the bacteriological analysis of cell phones of the multidisciplinary health team of a Municipal Health Unit in Belém, Pará State, Brazil; establish the sensitivity profile of the species found; and evaluate the adopted hygiene measures and the level of knowledge about microbial contamination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This is an analytical cross-sectional study in which questionnaires were applied and samples were collected from cell phones surfaces and cases. The samples were cultivated in blood agar and MacConkey medium, and bacterial identification was done through the application of specific tests. The antimicrobial sensitivity test was also performed using the disk diffusion method.

RESULTS:

Thirty-eight professionals participated in the study. Bacteria were detected in 94.7% (36/38) of the cell phones, with a predominance of Gram-positive species (82.2%) and, among these, 89.1% were resistant to penicillin G. The most prevalent species was Staphylococcus aureus (51.1%). Most respondents reported using the cell phone everywhere (97.4%) and during patient care (78.9%), 76.3% used to share it with other people, 68.4% washed their hands before or after using it and before patient care (92.1%), and 39.4% cleaned more than once a week with 70% alcohol (57.9%). In addition, most participants had a satisfactory level of knowledge about the microbial contamination of mobile phones; however, the samples from these professionals were significantly contaminated.

CONCLUSION:

Adopting correct personal and cell phone hygiene measures is essential to reduce the spread of bacteria between health professionals and patients.

Keywords: Cell Phone; Health Personnel; Bacteriological Analysis; Antibiogram; Hand Washing

INTRODUCTION

Cell phones are indispensable accessories for individuals in the social and professional sphere, and are often used by health professionals as an additional tool in diagnosing, monitoring, and treating patients in the nosocomial environment1. In this context, improper handling of these objects favors the growth and propagation of microorganisms, which can occur in two ways: indirectly, through aerosols; or direct, by contact with the mouth, ears, or skin2,3,4.

The use of mobile phones in hospital environments is constant among health professionals. When associated with inadequate hand and fomite hygiene, it results in contamination of these objects, which increases the risk of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs)2,5,6,7. HAIs occur in the hospital environment or other care units and are related to procedures performed by health professionals and the period of hospitalization in these places, regardless of the duration1,8.

Among the health care facilities, the Basic Health Units (Unidade Básica de Saúde - UBS) stand out, responsible for providing primary care and various services, from educational activities to minor surgical procedures1,9,10. In this way, these environments are conducive to microbiological proliferation because of the activities that expose both professionals and patients to risks of developing HAIs10,11,12.

In Brazil, studies have been carried out to investigate the prevalence of bacteria on surfaces of cellular devices of professionals in hospital environments. In these were found pathogenic bacteria, such as species of the genus Staphylococcus, the main ones were Staphylococcus aureus1,4,6,13,14, Staphylococcus epidermidis4, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus4; Streptococcus spp.14; and enterobacteria, such as Escherichia coli4,14, Enterobacter spp.4, Salmonella sp.4, Shigella sp.4, Pseudomonas sp.4,14, Proteus sp.4, and Klebsiella sp.4,14. However, no studies were carried out in UBS in Brazil, which reinforces the need for investigation in local health care services units.

It is essential to highlight that, in several UBS, protocols of norms and routines regarding hand washing, dressings, sterilization, and cleaning of environments are not adequately applied10,11,12. Thus, the objectives of the present study are: to carry out the bacteriological analysis of cell phones of the multi-professional health team of a Municipal Health Unit (Unidade Municipal de Saúde - UMS) in Belém, Pará State; establish the sensitivity profile of the species found; to evaluate the practices and hygiene measures adopted, and the level of knowledge of these professionals about microbial contamination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is an analytical cross-sectional study, carried out with health professionals from the Benguí II UMS, located in Belém, in the Administrative District of Benguí (DABEN), between September and November 2020. Questionnaires were applied, and samples were collected from respondents' cell phones. The sample number was obtained using the random sampling technique.

Only professionals who were present and who used cell phones in the unit were included in the research.

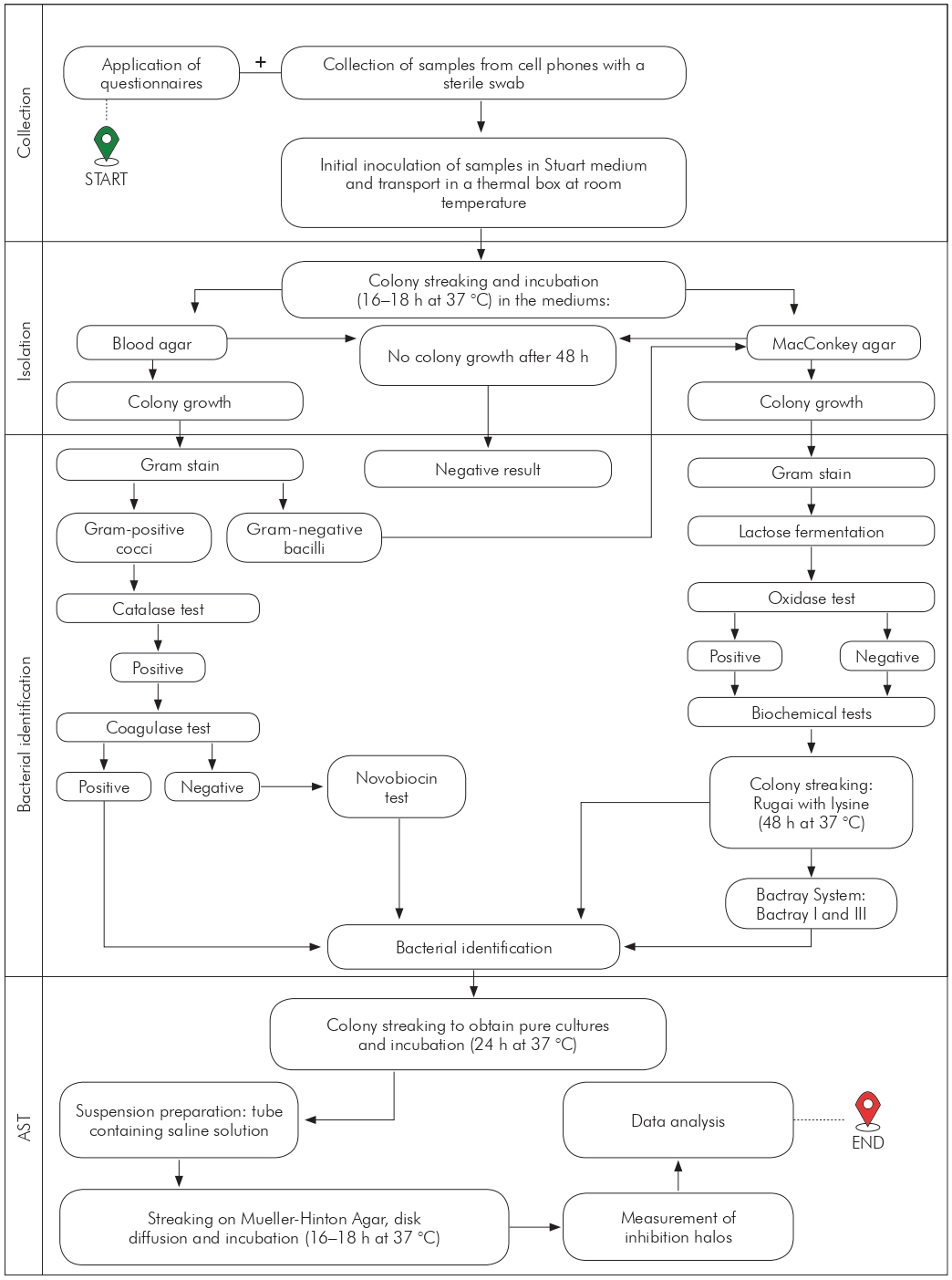

The figure 1 describes the adopted collection and laboratory analysis procedures.

AST: Antimicrobial sensitivity testing.

Figure 1 - Flowchart of activities for bacterial identification of cell phone samples collected at Benguí II UMS in Belém, Pará, Brazil, from September to November 2020

COLLECTION

Participants answered a multiple-choice questionnaire covering sociodemographic issues (gender, age, and profession), cell phone use and hygiene, and the level of knowledge about microbial contamination.

The sample collection was carried out using a sterile swab, which was rubbed on the front, side, and back surfaces and on the protective covers of the cell phones of each professional15. Then, the samples were stored in tubes containing the Stuart transport medium, identified, and immediately transported in a thermal box at room temperature to the UNIFAMAZ Microbiology Laboratory16.

LABORATORY ANALYSIS

The swabs were inoculated in blood agar and MacConkey culture medium through the qualitative streaking technique15,17. After the streaking, the culture plates were incubated in an oven at 37 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, bacterial growth was analyzed, and tests that showed at least one bacterial colony were validated as positive. In cases where no growth occurred, it was returned to the oven for another 24 h15.

The morphological identification of the bacteria isolated in the blood agar medium was performed using the Gram staining technique15. The catalase test was performed regarding the microorganisms identified as Gram-positive cocci, and for the positive ones, it was performed the coagulase test. In the case of negative coagulase, a sensitivity test to novobiocin was performed18.

The colonies isolated on MacConkey agar were submitted to Gram stain for morphological determination and to the oxidase test. Gram-negative bacilli that obtained negative or positive results were cultivated in Rugai medium with lysine (Laborclin®, Pinhais, Brazil)15. In inconclusive cases, Bactray systems I (oxidase negative) and III (oxidase positive) (Laborclin®, Pinhais, Brazil) were used to carry out additional biochemical tests.

The antimicrobial sensitivity testing (AST) of the isolates was developed through the disk diffusion method, following the recommendations of the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. The discs were selected according to the most commonly used antibiotics for the treatment of the most prevalent bacteria16, namely: cephalothin (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg) and penicillin G (10 µg), for Gram-positive bacteria; and ampicillin (10 µg), cefepime (30 µg), imipenem (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg), norfloxacin (10 µg), and tetracycline (30 µg), for Gram-negative bacteria.

Negative quality control was performed to verify the colony's growth by incubating the culture medium in an oven at 37 °C for 24-48 h. Positive quality control was performed by detecting strains sensitive to various antibiotics (E. coli ATCC 29522) and resistant to all antibiotics (Klebsiella pneumuniae ATCC 700603D-5).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, using the Microsoft Excel® program 2016. The chi-square test (χ2) was performed in the BioEstat® v5.0 software to verify statistically significant differences between the variables surveyed in the questionnaire and the percentages of bacterial contamination found on the cell phones of healthcare professionals. The significance level was p < 0.05.

ETHICAL ASPECTS

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Metropolitano da Amazônia (UNIFAMAZ), under nº 4,287,148, on September 18, 2020. The health professionals who agreed to participate in the study signed the Free and Informed Consent Form, in which the confidentiality and privacy of the information obtained were assured.

RESULTS

Among the 40 health professionals who worked at the Benguí II UMS, 38 agreed to participate in this study, with a response rate of 95.0%. As for sociodemographic factors, it was possible to observe a predominance of females (94.7%), age group between 22 and 39 years (55.3%), and professional nursing technician category (34.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1 - Sociodemographic information of healthcare professionals interviewed at Benguí II UMS in Belém, Pará, Brazil, from September to November 2020

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 36 | 94.7 |

| Male | 2 | 5.3 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 22 to 39 | 21 | 55.3 |

| 40 to 50 | 12 | 31.6 |

| 51 to 63 | 5 | 13.1 |

| Profession | ||

| Community health agent | 6 | 15.8 |

| Biomedic | 1 | 2.6 |

| Dentist | 1 | 2.6 |

| Nurse | 7 | 18.5 |

| Pharmacist | 1 | 2.6 |

| Physician | 3 | 7.9 |

| Nutritionist | 1 | 2.6 |

| Psychologist | 1 | 2.6 |

| Nursing technician | 13 | 34.3 |

| Oral health technician | 3 | 7.9 |

| Occupational therapist | 1 | 2.6 |

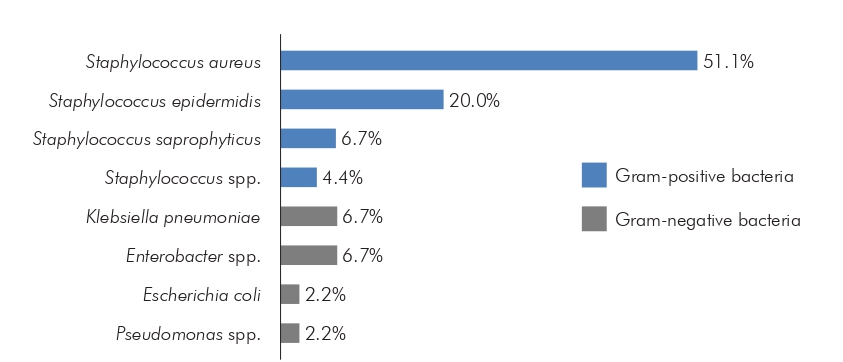

Bacteria were detected in 94.7% (36/38) of the cell phones. Among these, 80.6% (29/36) contained one, and 19.4% (7/36), more than one bacterial species, totaling 45 identified species. There was a predominance of Gram-positive species 82.2% (37/45), and the most prevalent bacterium was S. aureus (51.1%; 23/45), followed by S. epidermidis (20.0%; 9/45). Among Gram-negative species, Enterobacter spp. (6.7%; 3/45) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (6.7%; 3/45) were the most prevalent (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Bacterial species found on the cell phones of healthcare professionals at Benguí II UMS in Belém, Pará, Brazil, from September to November 2020

After performing the AST, greater sensitivity of Gram-positive species was observed regarding the antibiotics tested, except for penicillin G, in which the resistance rate stood out in all species. On the other hand, Gram-negative bacteria K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Enterobacter spp. were more resistant to ampicillin. Enterobacter spp. was also more resistant to cefepime and norfloxacin. K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp. showed resistance to the carbapenems imipenem and meropenem. Pseudomonas spp. was sensitive to all antibiotics tested (Table 2).

Table 2 - Sensitivity profile of bacteria identified in cell phone samples from Benguí II UMS professionals in Belém, Pará, Brazil, from September to November 2020

| Bacteria Gram-positive | Antibiotics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPL | CIP | CLI | CLO | GEN | PEN | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| S. aureus | S | 18 | 78.2 | 20 | 86.9 | 17 | 73.9 | 22 | 95.6 | 18 | 78.2 | 2 | 8.7 |

| I | 1 | 4.4 | 1 | 4.4 | 1 | 4.4 | - | - | 1 | 4.4 | - | - | |

| R | 4 | 17.4 | 2 | 8.7 | 5 | 21.7 | 1 | 4.4 | 4 | 17.4 | 21 | 91.3 | |

| S. epidermidis | S | 9 | 100.0 | 8 | 88.9 | 4 | 44.4 | 8 | 88.9 | 9 | 100.0 | 2 | 22.2 |

| I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R | - | - | 1 | 11.1 | 5 | 55.6 | 1 | 11.1 | - | - | 7 | 77.8 | |

| S. saprophyticus | S | 3 | 100.0 | 2 | 66.7 | 3 | 100.0 | 3 | 100.0 | 3 | 100.0 | - | - |

| I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R | - | - | 1 | 33.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 100.0 | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | S | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | - | - |

| I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R | 1 | 50.0 | - | - | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 100.0 | |

| Bacteria Gram-negative | Antibiotics | ||||||||||||

| AMP | CPM | IMP | MPM | NOR | TET | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| K. pneumoniae | S | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 2 | 66.7 | 2 | 66.7 |

| I | - | - | - | - | 1 | 33.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 | |

| E. coli | S | - | - | 1 | 100.0 | - | - | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 |

| I | - | - | - | - | 1 | 100.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R | 1 | 100.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Enterobacter spp. | S | - | - | - | - | 2 | 66.7 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 |

| I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 33.3 | |

| R | 3 | 100.0 | 3 | 100.0 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | |

| Pseudomonas spp. | S | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 |

| I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

S: Sensitive; I: Intermediary; R: Resistant; CPL: Cephalothin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; CLI: Clindamycin; CLO: Chloramphenicol; GEN: Gentamicin; PEN: Penicillin G; AMP: Ampicillin; CPM: Cefepime; IMP: Imipenem; MPM: Meropenem; NOR: Norfloxacin; TET: Tetracycline. Conventional sign used: - Numeric data equal to zero, not resulting from rounding.

Regarding the use of cell phones, most professionals (97.4%) reported using them everywhere, and 78.9% confirmed their use during patient care. In addition, these devices were significantly more contaminated compared to those that did not have the same behavior (p < 0.0001; p = 0.0005, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3 - Habits of use and hygiene of the cell phone of Benguí II UMS professionals in Belém, Pará, Brazil, from September to November 2020

| Variables | Total | Positive samples | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Use the cell phone everywhere | |||||

| Yes | 37 | 97.4 | 35 | 97.2 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.8 | |

| Cell phone use during patient care | |||||

| Yes | 30 | 78.9 | 29 | 80.6 | 0.0005 |

| No | 8 | 21.1 | 7 | 19.4 | |

| Sharing personal cell phone with other people | |||||

| Yes | 29 | 76.3 | 28 | 77.8 | 0.0015 |

| No | 9 | 23.7 | 8 | 22.2 | |

| Hand washing before or after cell phone use | |||||

| Yes | 26 | 68.4 | 24 | 66.7 | 0.0668 |

| No | 12 | 31.6 | 12 | 33.3 | |

| Hand washing before patient care | |||||

| Yes | 35 | 92.1 | 33 | 91.7 | < 0.0001 |

| No | 3 | 7.9 | 3 | 8.3 | |

| Frequency of cell phone cleaning | |||||

| More than once a day | 11 | 28.9 | 10 | 27.8 | 0.0133 |

| More than once a week | 15 | 39.4 | 14 | 38.9 | |

| Weekly | 5 | 13.2 | 5 | 13.9 | |

| Monthly | 2 | 5.3 | 2 | 5.5 | |

| Never | 5 | 13.2 | 5 | 13.9 | |

| Cell phone cleaning method | |||||

| None | 4 | 10.5 | 4 | 11.1 | 0.0023 |

| With 70% alcohol | 22 | 57.9 | 21 | 58.3 | |

| Other | 12 | 31.6 | 11 | 30.6 | |

* P-value obtained by the chi-square test (p < 0.05).

Sharing the cell phone with other people was a regular practice among 76.3% of respondents. These devices showed greater bacterial contamination than those not shared (p = 0.0015) (Table 3).

Most participants (68.4%) declared to sanitize their hands before or after using the cell phone; however, there was no significant difference in the positive samples between those who performed the cleaning or not (p = 0.0668). There was a predominance of professionals (92.1%) who reported washing their hands before caring for patients, but the level of contamination was significantly higher when compared to those who did not do this procedure (p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

As for the frequency of cleaning their cell phones, 39.4% performed this practice more than once a week. The number of positive samples was higher in devices that were cleaned more than once a week, compared to those that were cleaned more than once a day or less frequently (p = 0.0133). Although the majority stated that they cleaned the device with 70% alcohol (57.9%), their cell phones were significantly contaminated by bacteria compared to those who did not follow this procedure (p = 0.0023) (Table 3).

Overall, 42.1% of respondents (16/38) got five of the six questions right about knowledge about microbial contamination, and 23.7% (9/38) got the maximum number of correct answers.

When analyzing the low-complexity questions, 100.0% of the professionals knew which personal protective equipment should be used during the routine (p < 0.0001) and knew the correct way of hand hygiene in their work environment (p < 0.0001). In the medium complexity questions, 78.9% answered that the cell phone could be a way of transmitting diseases (p = 0.0015), and 81.6% knew which bacteria are frequently found in this object (p = 0.0005). However, the cell phones of these individuals showed a higher prevalence of bacteria than those who did not answered correctly (Table 4).

Table 4 - Analysis of the knowledge of Benguí II UMS professionals on microbial contamination in Belém, Pará, Brazil, from September to November 2020

| Variables | Complexity level | Total | Positive samples | p* value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Personal protective equipment that health professionals must use during a work routine | Low | |||||

| Correct alternative | 38 | 100.0 | 36 | 100.0 | < 0.0001 | |

| Incorrect alternative | - | - | - | - | ||

| The correct form of hand hygiene in a health service | Low | |||||

| Correct alternative | 38 | 100.0 | 36 | 100.0 | < 0.0001 | |

| Incorrect alternative | - | - | - | - | ||

| Cell phones as a way of transmitting diseases | Medium | |||||

| Correct alternative | 30 | 78.9 | 28 | 77.8 | 0.0015 | |

| Incorrect alternative | 8 | 21.1 | 8 | 22.2 | ||

| Types of bacteria found on cell phones | Medium | |||||

| Correct alternative | 31 | 81.6 | 29 | 80.6 | 0.0005 | |

| Incorrect alternative | 7 | 18.4 | 7 | 19.4 | ||

| Importance of cell phone hygiene while working | High | |||||

| Correct alternative | 26 | 68.4 | 24 | 66.7 | 0.0668 | |

| Incorrect alternative | 12 | 31.6 | 12 | 33.3 | ||

| Implementation of biosecurity standards aimed at the use of cell phones in health services | High | |||||

| Correct alternative | 19 | 50.0 | 18 | 50.0 | 1.000 | |

| Incorrect alternative | 19 | 50.0 | 18 | 50.0 | ||

* p-value obtained using the chi-square test (p < 0.05). Conventional sign used: - Numeric data equal to zero, not resulting from rounding.

In the highly complex questions, it was found that 68.4% considered essential cleaning the cell phone during the work routine (p = 0.0668), and 50.0% knew the reason for the implementation of biosafety standards aimed at the use of cell phones in health services (p = 1.000). However, the samples' microbial contamination was similar in all devices, regardless of the alternative marked in the questionnaire (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

A cell phone is an object capable of harboring microorganisms, becoming a possible way of transmitting bacteria between professionals and their patients5,14. Thus, the present study identified a high rate of bacterial contamination in 94.7% (36/38) of the mobile devices of professionals working in a UMS in Belém.

This investigation was the first carried out in the Northern Region of Brazil regarding detecting bacteria in these objects in a health care environment. Studies with similar results, conducted with health professionals in the hospital environment in Ethiopia and Colombia, showed a bacterial contamination rate of 94.2% (213/226)14 and 97% (38/39)1, respectively. In Brazil, a survey carried out with students and health professionals from an Intensive Care Unit in Rio de Janeiro also showed a similar result, with 100% (50/50) of contaminated phones6, reinforcing the importance of adopting control measures to prevent the occurrence of HAIs associated with contact with these fomites.

In this study, Gram-positive bacteria were predominant (82.2%; 37/45) compared to Gram- negative bacteria 17.8% (8/45), which corroborates a study carried out on cell phones of health professionals in a hospital in Ethiopia, in which the frequency of Gram-positive was 79.2% (171/216) and Gram-negative, 20.8% (45/216)14. Likewise, Nunes and Siliano15, when investigating the cell phones of university students in São Paulo, identified a higher proportion of Gram-positive bacteria when compared to Gram-negative bacteria.

The high prevalence of Gram-positive bacteria in the devices is possibly related to their presence in the normal human microbiota and their resistance to drying, a factor that favors adherence and survival in the environment. On the other hand, the low frequency of Gram-negative bacteria can be explained because they are transient microorganisms, and can be easily removed by performing adequate hand hygiene with soap and water2.

Regarding the identified species, S. aureus was prevalent in 51.1% (23/45) of the samples, as well as in studies carried out with university students, health professionals, and food handlers4,5,15. These bacteria are present in the skin microbiota of individuals and can colonize various objects, such as phones, doorknobs, and others. In addition, it is the most frequent Gram-positive pathogen in hospital infections, causing skin and subcutaneous problems from anthrax, furuncle, impetigo, and cellulitis to systemic involvement, including bacteremia, endocarditis, pneumonia, septicemia, and others18.

The occurrence of S. epidermidis (20.0%; 9/45) and S. saprophyticus (6.7%; 3/45) was an important finding, which was also observed in cell phones of university students, health professionals, and food handlers in Rondônia State, where these species were observed in 11.7% (7/60) and 40.0% (24/60) of the samples, respectively4. The bacteria S. epidermidis can be found on the skin and mucous membranes, and it is considered an opportunistic pathogen, which can cause systemic infections18. The S. saprophyticus is often found in the genitourinary region, triggering urinary tract infections17,18.

Enterobacter spp., E. coli, and K. pneumoniae, belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae, were identified among the Gram-negative bacteria isolated in this study. Enterobacteria are capable of causing infections in humans and can be found in water, soil, vegetables, and food19. These bacteria may indicate contamination of fecal origin19, which reinforces the importance of hand and cell phones hygiene.

In an analysis carried out with professionals and students from a health center in Alexandria, Egypt, K. pneumoniae was identified in 7.5% (3/40) of cell phone samples and E. coli in 12.5% (5/40)20. These data differ from the present study, which found 6.7% (3/45) and 2.2% (1/45) of these species, respectively.

K. pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen, as it has virulence factors such as capsule, lipopolysaccharides, and fimbriae. It is associated with pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and hospital infections21.

Strains of E. coli reside in the colon without causing harm to the body of healthy individuals. However, some pathogenic strains are capable of triggering intestinal and extraintestinal problems in hosts, such as gastroenteritis, urinary infections, and even septicemia18.

Enterobacter spp. is present in the intestinal tract of humans and animals and can cause pneumonia and urinary tract infections18. In the present study, 6.7% (3/45) of the samples were contaminated by this bacterium, as in the investigation by Araújo et al.4, which identified 38% (8/21) of this microorganism in cell phones, indicating enteric contamination.

In the present study, another relevant finding was the identification of Pseudomonas spp. in 2.2% (1/45) of the samples. This bacterium was also found by Bodena et al.14 in 3.7% (8/216) of cell phone samples from healthcare professionals at a hospital in Ethiopia. Despite being found less frequently in this analysis, the detection of a bacterium considered opportunistic is an alert. This pathogen can adapt to the environment, which is related to virulence factors, such as the ability to adhere and form a biofilm, favoring high resistance to disinfectants and antibiotics18,22.

Antimicrobial resistance is a public health problem, especially regarding recurrent infections in hospital environments23,24,25. As for the antimicrobial susceptibility profile, all bacterial species isolated were resistant to at least one antibiotic. This finding may reflect the indiscriminate use of antibiotics for different reasons, such as self-medication, inappropriate dosages, errors during drug prescription, or intrinsic resistance26,27.

As for the results of the AST, the antimicrobial chloramphenicol, which has a bacteriostatic action26, was effective against most Gram-positive bacteria detected on cell phones, with the highest sensitivity rates. This sensitivity profile was observed in other studies carried out with the mobile devices of healthcare professionals in hospitals14,20.

Concerning penicillin G, a high resistance profile was detected in Gram-positive species. This data agrees with studies carried out in different parts of the world13,23. Stuchi et al.13 reported that more than 70% of strains isolated of S. aureus and S. epidermidis were resistant to this antibiotic, both in the hospital environment and in the community, confirming the reduction of its effectiveness against staphylococcal infections.

Regarding the antibiotics tested against Gram-negative bacteria, higher sensitivity rates to meropenem, a broad-spectrum β-lactam of the carbapenem class, were observed28. In contrast to this result, in cellular devices of professionals in an operating room in Pakistan, a resistance profile was detected in 100% (3/3) and 80% (8/10) in the species Enterobacter sp. and Pseudomonas sp., respectively, for this antibiotic29. These findings evidence the presence of an acquired resistance mechanism associated with the expression of β-lactamases enzymes capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems30.

On the other hand, most Gram-negative species were resistant to ampicillin, a broad-spectrum β-lactam of the aminopenicillin class25. Similarly, a study carried out with healthcare professionals from a hospital in Nigeria obtained a resistance profile equivalent to 100.0% (33/33) for ampicillin16, suggesting an increase in the acquisition of resistance, motivated by the widespread use of this antibiotic in an uncontrolled way31.

Two species were also detected (K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp.) resistant to the carbapenems imipenem and meropenem simultaneously. This resistance is considered a public health problem, as infections caused by enterobacteria represent a high risk of mortality and a limitation in therapeutic options30.

Regarding cell phones, it was found that 97.4% (37/38) of professionals used them repeatedly everywhere. This data is in agreement with the study by Muñoz Escobedo et al.5, carried out with employees and students of the academic unit of Dentistry of a multidisciplinary clinic in Mexico, and with a survey carried out with students of a higher education institution in Teresina, Piauí State, Brazil31, which obtained a rate of 81% (42/52) and 75% (41/55), respectively. In addition, 78.9% (30/38) claimed to use cell phones in the course of patient care. This data differs from Muñoz Escobedo et al.5, in which 21% (11/52) of those surveyed were used to handle the devices even with gloves during care.

Most respondents (76.3%) stated that they shared their cell phone with other people they interact with, corroborating the finding made by Bodena et al.14, in which 74.8% (169/226) of Ethiopian health professionals used to share the device with co-workers.

These practices can facilitate microbiological proliferation in mobile phones since using the device in bathrooms, during meals, or sharing it with others increase the risk of microbial contamination2. This fact was confirmed by the positivity of the samples of those individuals who claimed to use the cell phone everywhere, during the service, and share it with other people. This demonstrates the importance of avoiding using these devices during care, minimizing the ways of contamination, especially when wearing gloves, since there is contact with the patient and, consequently, with possible microorganisms2.

As for hand hygiene, 68.4% (26/38) said they did it before or after using the cell phone, and 92.1% (35/38) said they washed their hands before caring for patients. In contrast, in the study carried out in Ethiopia, 26.1% (59/226) had the habit of cleaning, and 76.5% (173/226) did not adhere to washing hands before seeing patients14.

Although health professionals stated that they washed their hands before attending to patients, the number of positive samples was high (91.7%), suggesting that the contamination may be intrinsic or associated with other habits. This data highlights the need for personal hygiene and cell phone cleaning before and after each service to reduce microbial contamination2.

It was also observed that 39.4% (15/38) of the participants cleaned their cell phones more than once a week. In contrast, only 1.8% (1/55) of physiotherapy students and professionals interviewed by Sousa et al.31 and 13% (7/52) of students in a multidisciplinary clinic in Mexico5 performed this practice. This frequency was inadequate because the cell phones of these professionals were significantly contaminated (14/15). The same happened with those who performed the cleaning more than once a day (10/11), indicating the need to perform this procedure daily, before and after patient care, and at the end of the day, to reduce bacterial contamination in these devices.

The proper cleaning of cell phones using 70% alcohol is considered an effective procedure, as it is a very effective bactericide that denatures the proteins of microorganisms, including fungi and viruses2,32.

Of the professionals interviewed, 57.9% (22/38) claimed to use 70% alcohol to clean their cell phones, similar to the study by Sousa et al.31, in which 51% (18/35) cleaned the device in this way. However, 58.3% (21/36) of the samples in this study were contaminated, showing that this cleaning may not be done correctly.

Regarding the level of knowledge of professionals about microbial contamination in cell phones, few studies in the literature evaluated this problem14,33. In the present study, 42.1% (16/38) of the interviewees got five of the six questions correct, corresponding to a good performance of these participants. However, this satisfactory result was not reflected in the level of bacterial contamination of the samples, which may be related to the difficulty of interpreting more complex issues that required specific knowledge, evidencing the need to carry out qualification and training on the subject.

The study showed that 100.0% (38/38) of the professionals knew the personal protective equipment and the correct way of hand hygiene during their routine at the health unit. However, 100.0% (36/36) of the device samples were positive, demonstrating that knowing this information was not enough to reduce contamination.

In addition, 78.9% (30/38) of respondents knew that cell phones could be a way of transmitting diseases. This result corresponds to an investigation carried out with health professionals, in which 80.1% (181/226) stated that the mobile device could carry bacteria and cause diseases14, and a study carried out with medical students at a hospital in Iran, in which 100% (30/30) claimed to have this knowledge33.

It was found that 81.6% (31/38) of respondents knew the main bacteria isolated from cell phones. These were also the most found in this analysis, confirming the data found in the literature on the contamination of these objects by bacteria1,4,6,13,14.

Concerning the importance of hygiene and the implementation of biosafety standards aimed at the use of cell phones in health services, 68.4% (26/38) and 50.0% (19/38) of professionals considered essential to carry out these practices, respectively. In this sense, it is important to highlight that several UBS do not have protocols of standards and routines for cleaning environments10,11,12, which may explain the presence of bacterial contamination in the analyzed cell phones.

It is also worth mentioning the limitations of the study, characterized by the small sample size, justified due to the time delimited for the research, which punctually took place, with no possibility of performing temporal analyses, in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted the UMS operating logistics, culminating in reduced teams, thus interfering with sampling.

CONCLUSION

This study showed a high frequency of bacterial contamination on the surfaces of the mobile phones of professionals from Benguí II UMS, even though the investigated population stated that they know and carry out the appropriate hygiene practices. Although most of the species found are part of the normal microbiota, bacteria of clinical importance were detected, which brings an alert to the community.

The findings reinforce the importance of raising awareness and adopting standardized protocols for personal hygiene and cell phone cleaning to control bacterial spread among professionals and patients and, thus, reduce the risks of healthcare-associated infections in UBS. Cleaning can be carried out simply with 70% alcohol before and after each medical service. Finally, there is a need for more studies in the context of UBS, with a larger sample number and a temporal analysis, given the paucity of studies in the literature.

REFERENCES

1 Castaño Jiménez PA, Sánchez Ramírez MC, Echeverry Moreno PA, Lucia Aguirre O. Determinacion de bacterias patogenas en telefonos celulares del personal de salud en un hospital de la ciudad de manizales. Microciencia. 2017 dic;6(5):51-60. Doi: 10.18041/2323-0320/microciencia.0.2017.3660 [Link] [ Links ]

2 Baldo A, Freitas AFM, Santos RCC, Souza HC. Contaminação microbiana de telefones celulares da comunidade acadêmica de instituição de ensino superior de Araguari (MG). Rev Master. 2016 jan-jun;1(1):57-65. Doi: 10.5935/2447-8539.20160005 [Link] [ Links ]

3 Koscova J, Hurnikova Z, Pistl J. Degree of bacterial contamination of mobile phone and computer keyboard surfaces and efficacy of disinfection with chlorhexidine digluconate and triclosan to its reduction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Oct;15(10):2238. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102238 [Link] [ Links ]

4 Araújo AM, Novais VP, Calegari GM, Góis RV, Sobral FOS, Marson RF. Ocorrência de microrganismos em aparelhos celulares no município de Ji-Paraná-Rondônia, Brasil. Braz J Surg Clin Res. 2017 jun-ago;19(1):10-5. [Link] [ Links ]

5 Muñoz Escobedo JJ, Varela Castillo L, Chávez Romero PB, Becerra Sánchez A, Moreno García MA. Bacterias patógenas aisladas de teléfonos celulares del personal y alumnos de la clínica multidisciplinaria (CLIMUZAC) de la unidad Académica de Odontología de la UAZ. Arch Venez Farmacol Ter. 2012 jun;31(2):23-31. [Link] [ Links ]

6 Reis LE, Silva W, Carvalho EV, Costa Filho A, Braz MR. Contaminação de telefones celulares da equipe multiprofissional em uma unidade de terapia intensiva. Saber Digital. 2015 nov;8(1):68-83. [Link] [ Links ]

7 Silva LS, Leite CA, Azevedo DSS, Simões MRL. Perfil das infecções relacionadas à assistência à saúde em um centro de terapia intensiva de Minas Gerais. Rev Epidemiol Controle Infecç. 2019 out;9(4):1-11. Doi: 10.17058/.v9i4.12370 [Link] [ Links ]

8 Pereira FGF, Chagas ANS, Freitas MMC, Barros LM, Caetano JÁ. Caracterização das infecções relacionadas à assistência à saúde em uma Unidade de Terapia Intensiva. Vigil Sanit Debate. 2016 nov;4(1):70-7. Doi: 10.3395/2317-269x.00614 [Link] [ Links ]

9 Ministério do Planejamento (BR). UBS-Unidade Básica de Saúde [Internet]. Brasil: Ministério do Planejamento/PAC; 2016 [citado 2020 nov 20]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://pac.gov.br/infraestrutura-social-e-urbana/ubs-unidade-basica-de-saude . [ Links ]

10 Freitas TS, Quirino GS. Esterilização em unidades básicas de saúde no município de Picos-PI. Sanare. 2011 jul-dez;10(2):57-63. [Link] [ Links ]

11 Paula FMS, Beserra NCN, Lopes RCS, Guerra DR. Elaboração de material didático para processamento de produtos para saúde em unidades de atenção primária à saúde. Rev SOBECC. 2017 set;22(3):165-70. [Link] [ Links ]

12 Santos L, Bonagrazia TMM, Dias-Junior JL, Ferro DAM. Contagem de micro-organismos em determinados locais da Unidade Básica de Saúde em Aspásia-SP. Unifunec Ci Saude Biol. 2020 jan-dez;3(6):1-13. Doi: 10.24980/ucsb.v3i6.3443 [Link] [ Links ]

13 Stuchi RAG, Oliveira CHAS, Soares BM, Arreguy-Sena C. Contaminação bacteriana e fúngica dos telefones celulares da equipe de saúde num hospital em Minas Gerais. Cienc Cuid Saude. 2013 dez;12(4):760-7. Doi: 10.4025/cienccuidsaude.v12i4.18671 [Link] [ Links ]

14 Bodena D, Teklemariam Z, Balakrishnan S, Tesfa T. Bacterial contamination of mobile phones of health professionals in Eastern Ethiopia: antimicrobial susceptibility and associated factors. Trop Med Health. 2019 Feb;47(15). Doi: 10.1186/s41182-019-0144-y [Link] [ Links ]

15 Nunes KO, Siliano PR. Identificação de bactérias presentes em aparelhos celulares. Sci Health. 2016 jan-abr;7(1):22-5. [Link] [ Links ]

16 Nwankwo EO, Ekwunife N, Mofolorunsho KC. Nosocomial pathogens associated with the mobile phones of healthcare workers in a hospital in Anyigba, Kogi state, Nigeria. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2014 Jun;4(2):135-40. Doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.11.002 [Link] [ Links ]

17 Brooks GF, Carroll KC, Butel JS, Morse SA, Mietzner TA. Microbiologia médica de Jawetz, Melnick e Adelberg. 26. ed. Porto Alegre: AMGH Editora; 2014. [ Links ]

18 Levinson W. Microbiologia médica e imunologia. 13. ed. Porto Alegre: McGraw- Hill; 2016. [ Links ]

19 Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (BR). Microbiologia clínica para o controle de infecção relacionada à assistência à saúde. Módulo 6: Detecção e identificação de bactérias de importância médica. Brasília: Anvisa; 2013. [Link] [ Links ]

20 Selim SH, Abaza AF. Microbial contamination of mobile phones in a health care setting in Alexandria, Egypt. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2015 Feb;10:Doc03. Doi: 10.3205/dgkh000246 [Link] [ Links ]

21 Tessmann BA, Caballero PA, Martins AF, Perez VP. Emergência de resistência antimicrobiana em Klebsiella spp. em município do interior do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. R Epidemiol Control Infec. 2017 out;7(4):215-20. Doi: 10.17058/reci.v7i4.9345 [Link] [ Links ]

22 Gupta R, Malik A, Rizvi M, Ahmed SM. Incidence of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas spp. in ICU patients with special reference to ESBL, AMPC, MBL and biofilm production. J Glob Infect Dis. 2016 Jan-Mar;8(1):25-31. Doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.176142 [Link] [ Links ]

23 Silva NFV, Kimura CA, Coimbra MVS. Perfil de sensibilidade antimicrobiana das Pseudomonas aeruginosa isoladas de pacientes da unidade de tratamento intensiva de um hospital público de Brasília. Revisa. 2012 jan-jun;1(1):19-24. [Link] [ Links ]

24 Tascini C, Sozio E, Viaggi B, Meini S. Reading and understanding an antibiogram. Ital J Med. 2016;10(4):289-300. Doi: 10.4081/itjm.2016.794 [Link] [ Links ]

25 Costa ALP, Silva Jr AC. Resistência bacteriana aos antibióticos e saúde pública: uma breve revisão de literatura. Estação Científica (UNIFAP). 2017 mai-ago;7(2):45-57. Doi: 10.18468/estcien.2017v7n2.p45-57 [Link] [ Links ]

26 Garcia JVAS, Comarella L. O uso indiscriminado de antibióticos e as resistências bacterianas. Cad Saude Desenvolv. 2018;13(7):93-105. [Link] [ Links ]

27 Costa JM, Moura CS, Pádua CAM, Vegi ASF, Magalhães SMS, Rodrigues MB, et al. Medida restritiva para comercialização de antimicrobianos no Brasil: resultados alcançados. Rev Saude Publica. 2019 ago;53:68. Doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2019053000879 [Link] [ Links ]

28 Magalhães VCR, Soares VM. Análise dos mecanismos de resistência relacionados às enterobactérias com sensibilidade diminuída aos carbapenêmicos isoladas em um hospital de referência em doenças infecto-contagiosas. Rev Bras Anal Clin. 2018 dez;50(3):278-81. Doi: 10.21877/2448-3877.201800661 [Link] [ Links ]

29 Qureshi NQ, Mufarrih SH, Irfan S, Rashid RH, Zubairi AJ, Sadruddin A, et al. Mobile phones in the orthopedic operating room: microbial colonization and antimicrobial resistance. World J Orthop. 2020 May;11(5):252-64. Doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i5.252 [Link] [ Links ]

30 Lavagnoli LS, Bassetti BR, Kaiser TDL, Kutz KM, Cerutti Jr C. Fatores associados à aquisição de enterobactérias resistentes ao carbapenêmicos. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2017;25:e2935. Doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.1751.2935 [Link] [ Links ]

31 Sousa DL, Morais FRS, Paz FAN, Silva LL. Análise microbiológica de aparelhos celulares de acadêmicos de fisioterapia de uma faculdade privada de Teresina (PI). Rev Cienc Saude. 2018 abr-jun;8(2). Doi: 10.21876/rcsfmit.v8i2.753 [Link] [ Links ]

32 Silva LA, Mutran TJ, Bouças RI, Bouças TRJ. Identificação e prevenção de microrganismos presentes nos aparelhos celulares de alunos e funcionários da universidade cidade de São Paulo. Science Health. 2015 mai-ago;6(2):118-23. [Link] [ Links ]

33 Jalalmanesh S, Darvishi M, Rahimi M, Akhlaghdoust M. Contamination of senior medical students' cell phones by nosocomial infections: a survey in a university-affiliated hospital in Tehran. Shiraz E Med J. 2017 Mar;18(4):e59938. Doi: 10.5812/semj.43920 [Link] [ Links ]

Received: January 16, 2021; Accepted: December 09, 2021

texto em

texto em